In my previous article, “The ‘Three Highs and One Low’ Phenomenon of Overseas Chinese Churches,” I aimed to depict the current state of most Chinese immigrant churches outside of China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. These churches are characterized by high mobility, high diversity, high competition, and low sustainability.

A valuable resource that every pastor and believer leader serving overseas should consider is the research report “Listening to Their Voices” (LTTV), shared by Professor Enoch Wong of Canada in 2018.

Professor Enoch Wong recognizes the value and contribution of overseas Chinese churches. They play a crucial role by providing social, material, and psychological support. They preserve Chinese culture, values, and traditions, thereby becoming an essential social capital. They provide a space for inheritance, allowing the traditions, customs, language, and identity of the previous generation to be passed on to the second generation of immigrants. Furthermore, the first generation of male immigrants can restore their original leadership position within the religious organization. The positive contributions of Chinese immigrant churches include uniting immigrants, maintaining and inheriting culture, and the leadership role and status of male immigrants within the group.

The “Three Highs and One Low” phenomenon I observed is something that most Chinese pastors in the United States, Canada, Australia, and the UK are likely familiar with. These are not new knowledge, but rather a reorganization of general observations. Pastors serving in overseas congregations are mostly aware of the problems of institutional habits. Indeed, it is not easy to raise questions and prescribe the right medicine.

There is a co-dependent relationship between the pastor and the immigrant church. When pastors question and criticize the churches they serve and their Chinese church circles, it is like shooting oneself in the foot—it is self-inflicted trouble and harm to personal interests. The overseas Chinese church circle is even narrower, and there are many rights and wrongs in the small circle. Offending the vested interests of the group may ruin one’s future.

By gaining a true and accurate understanding of Chinese immigrant churches, their distinct characteristics compared to churches of China, of Hong Kong, and of Taiwan, as well as their high mobility and low sustainability, we can avoid unnecessary anxiety about fluctuations in church meetings. Additionally, we should refrain from setting unrealistic expectations and demands for devoted pastors. The previous article discussed the phenomenon, while this article aims to propose a solution. It is often difficult for large organizations with numerous people and power structures to make significant changes. However, Chinese immigrant churches with less seniority and smaller congregations of less than a hundred members may find it more feasible to implement changes.

1. From High Mobility to “People on the Move”

As I pointed out in the previous article, the increase or decrease in the number of overseas Chinese churches is based on the influx and outflow of immigrants. If overseas Chinese churches continue to pursue the growth of the number of people as an indicator, it will only cause self-inflicted pain.

Facing high mobility, overseas Chinese churches need to rethink their positioning and role, similar to that of a chaplain. Whether in a hospital as a hospital chaplain, in a school as a school chaplain, or in a foreign country, chaplains combine the functions of hospital and school pastors: caring for the physical and mental needs of immigrants, assisting immigrants in adapting to identity and life changes, and equipping immigrants to become missionary disciples.

The chaplain has a specific role and contribution, regardless of the number of attendees. Realistically, most overseas Chinese churches are indeed maintaining the first generation of immigrants, and it is difficult to develop their second generation.

In fact, the overseas Chinese church is more like a school chaplain’s office, which may be the right direction. Individual churches no longer pursue the expansion of their own organizations and venues, knowing their own limitations and opportunities. Facing at least a quarter of college students who graduate and leave each year, the school chaplain’s office understands that its mission is to unite Christians in the school, assist students in adapting to college life, and equip them to become missionary disciples after leaving campus.

Facing a congregation frequently on the move, whether it is returning to the original place of residence, moving to another city due to work, family, children’s schooling, living costs, or any other reason, overseas Chinese churches no longer focus on the “flow” of its congregation, but value the “dispersion” quality. Like a hospital chaplain, they do not expect hospitalized patients to stay for a long time, thereby confirming the value of the existence of the hospital chaplain. Instead, they expect patients to be discharged normally after recovery and contribute to society.

The same is true for immigrant churches. The pastor faithfully takes care of the first generation of immigrants and also equips the congregation to become “people on the move” (mission disciples), not to be comfortable in the same cultural, geographical, and linguistic environment for a long time, but to cross cultural, geographical, and linguistic boundaries into the unfamiliar “foreign land.”

In 2023, the Lausanne Movement issued Lausanne Occasional Paper 70: “People on the Move,” highlighting the challenges that global population mobility poses to missionary work.

The Lausanne Movement and Global Diaspora Network (GDN) believe God is sovereign over human dispersion and the new reality of migration worldwide can accelerate the mission of God globally.…

The Christian faith is diasporic at its core. It is meant to go places which means that the epicenter of the faith always shifts from place to place. The movement of people is of the utmost consequence to Christianity, as migrants and diaspora communities have shaped and reshaped the contours of its growth and spread throughout history. Christian faith moves because Christianity is quintessentially a missionary faith.…

…All missionaries are migrants for having to cross national or cultural boundaries. Likewise, all Christian migrants could be considered potential missionaries as they carry out the missionary functions of diffusing the gospel cross-culturally. (Quotations taken from “Lausanne Occasional Report 70—People on the Move.”)

Chinese churches abroad, along with their pastors and leaders, need to reinterpret the experiences of this group of “strangers” (a term denoting the self-perception of the first generation of immigrants) journeying to “strange places” (new countries and regions), and continually reflect on their faith. Whether consciously or not, these first-generation immigrants from Hong Kong who have left their original place of residence are continually dialoguing, communicating, and integrating with their new environments. The role of the Chinese church is to guide believers in exploring their identity and mission.

I am convinced that overseas Chinese churches must begin within their own communities and have no choice but to engage in local cross-cultural evangelism. Neighbors, colleagues, children’s classmates, and friends all come from diverse ethnicities, languages, and cultures. The practice of mission disciples is to “entertain strangers,” inviting Hindus, Muslims, or people from other cultures to share a meal at home and building relationships in everyday life.

2. Transition from High Hybridity to “Hybrid Community”

The congregation of overseas Chinese churches is not from a monoculture, which is why multiculturalism provides an opportunity for the church to become a learning and exchange center for local cross-cultural evangelism. The vision of pastors and leaders extends beyond the development of their own ministries and is directed towards God’s mission, the missio dei.

The concept of a hybrid community has two dimensions: first, culture, which refers to the “intermediate form of two different cultures”1; second, mission, which refers to the “hybrid car” that carries out the mission.

For the first generation of immigrants, the struggle between preserving their original culture and fully embracing the new culture of their adopted city is a personal journey with no predetermined or standard answers. The role of overseas Chinese churches is to guide their congregation in confronting their “hybrid” identity, jointly interpreting, sorting out, sharing, and thereby exemplifying unity in diversity.

The emphasis of the hybrid community is not on unification or uniformity, but on acknowledging the history, culture, values, and stories of each first-generation immigrant, learning to respect and accept differences, and working collectively to fulfill the kingdom mission.

The experiences of many immigrant churches reveal that “long-term cohesion only leads to disputes and internal consumption.” The pastoral challenge for pastors and leaders is to shift the congregation’s vision from an inward-looking perspective to an outward-looking kingdom view.

In mid-January 2024, I had the opportunity to share about the partnership of the Hong Kong Christian community who moved to the UK with church leaders in Leeds. I mentioned that the Hong Kong Association of Christian Missions (香港差傳事工聯會) released the “Hong Kong Missionary Statistics” in 2022, which showed that 34 missionaries were in the UK (the third-highest area with Hong Kong dispatched missionaries). At the same time, it is estimated that at least 150,000 Hong Kong residents have settled in the UK with BNO visa status. If we assume that 20% of the Hong Kong immigrant population are Christians, there are at least about 30,000 Christians.

Naturally, not every Christian in Hong Kong is tasked with spreading the gospel. However, if even a tenth, or 3,000 “mission disciples” (people on the move), are willing to become carriers of the mission, they can spread the word of the Lord, regardless of their blood ties, geographical ties, professional ties, educational ties, interest ties, or ties of pain. Wherever they go, they carry the Lord’s mission with them.

3. From Intense Competition to “Partnership in the Gospel”

Every overseas Chinese church needs to reflect on its identity and role in its specific country and city. When they recognize their unique identity and mission, there is no need for pointless comparisons or unhealthy competition with others.

Pastors and leaders should learn to have the same breadth of spirit as Paul: “What then? Only that in every way, whether in pretense or in truth, Christ is proclaimed, and in that I rejoice. Yes, and I will rejoice” (Philippians 1:18).

A mission is defined as a “partnership” when two or three groups come together to pray, plan, share, and utilize resources with the deliberate intention of working together to realize the common vision given by God, thereby advancing the kingdom of God in ways that individual groups cannot. Partnership in the gospel means there is no need for “what others have, I have.” Resources can be shared, and manpower can be supplemented.

Many Chinese churches’ English ministry—usually targeting the second generation of believers—often operates in a state of limbo. I generally advise new Hong Kong churches against rushing into it. “There is a great need” does not necessarily mean “must do,” and the strategy is not necessarily “do it yourself.” I suggest that English ministry or children and youth ministry can collaborate with nearby local English churches or organizations.

In 2015, Dr. Enoch Wong visited Hong Kong to discuss the phenomenon of the second generation of believers leaving the church in Canada:

The second generation of believers in Canada were born and raised here, and their ethnic identity and values are vastly different from those of the first generation of immigrant parents. In the past, parents were xenophobic towards ethnic groups, but the second generation supports the acceptance of multiple ethnic groups and believes that the church cannot only serve the Chinese community (Christian Weekly, Issue 2676, December 6, 2015).

The second generation of immigrants, raised in a multicultural and ethnic environment, expect immigrant churches to not only serve the first generation of Chinese or Hong Kong immigrants, but also other East Asian, Middle Eastern, Central American, African, Eastern European, and other immigrants. If the Cantonese church serves Hong Kong people, and the Mandarin church serves Chinese people, then who should the English church serve? This is a question that overseas Chinese churches must confront and consider. Local cross-cultural mission is not a short-term mission to foreign countries but begins with the positioning and direction of the English church.

As Chinese churches, we can collaborate in the ministries of different age groups. If a church excels in elderly ministry, we don’t have to replicate it, and we don’t mind sending the elderly to participate in the meetings of that church. Pastors and leaders can view the entire city as a pastoral area, and all the churches in that pastoral area—local English churches, Chinese churches, Hong Kong churches, Hong Kong fellowships and Bible study classes, and so on—are sacred and public churches. Pastors and leaders shouldn’t worry about where the first generation of immigrants go to worship.

Only when we reaffirm that kingdom growth is more important than church growth can we see that the two are not necessarily opposed, and that church growth can promote kingdom growth.

Conclusion

Chinese churches in the United States, Canada, Australia, and the UK have experienced the trials and tribulations of Chinese immigrants and have traversed many challenging paths. The contributions of our predecessors cannot be denied, and overseas Chinese churches have their unique identity and position. As the British immigrant church is taking off, the Canadian Cantonese church is once again experiencing a “sunset glow.” We should not let the immigration fever cloud our judgment and keep repeating the mistakes of our predecessors.

Overseas Chinese churches need to equip immigrant congregations to become people on the move, learn to grow and blend together in mixed groups, achieve cross-cultural missions together, and establish gospel partner relationships with other churches, instead of going it alone. I believe learning in these three directions is the way forward. Even if one day, a Chinese church (I mean a church with low sustainability, and it should be quite good to have a 50-year history) has fewer people and closes, it is not a shameful thing.

Whether overseas Chinese churches can adapt appropriately may depend on whether the leaders in power can renew their thinking, dare to try, and create a broader horizon for themselves and the next generation!

Reference Material

“Listening to Their Voices” (LTTV)

Lausanne Occasional Paper 70—”People on the Move”

Editor’s note: This article was originally written in Chinese and was translated by the ChinaSource team. Original source: 海外華人教會「三高一低」的轉身.

Endnotes

- 陈国贲着《漂流:华人移民的身份混成与文化整合》,42頁

Image credit: Erika Giraud via UnSplash.

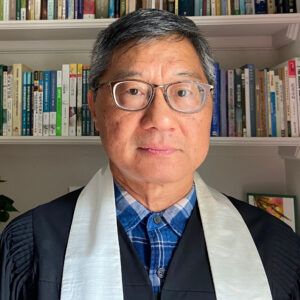

Chi Wai Wu

Rev. Dr. Chi Wai Wu (胡志偉), an ordained Christian and Missionary Alliance minister from Hong Kong, now resides in Bristol. He pastored Yuen Kei Alliance Church (1984–2000) and led the Hong Kong Church Renewal Movement (2000–2020). In 2021, he moved to the UK, advocating for Hong Kong Christians' integration into …View Full Bio