“What could be discovered if Pentecostals in Hong Kong were put on a map?” Alex Mayfield, then a PhD student at Boston University and now a history professor at Asbury University, first raised that question in 2017. He was trying to puzzle out the early history of Pentecostalism on the island.

Encouraged by his Chinese history professor, Eugenio Menegon, Mayfield went through over a thousand Pentecostal periodicals and tracked the movements and activities of Pentecostals in Hong Kong up to 1942. The addresses of their homes, chapels, orphanages, and the like were recorded, along with the names, nationalities, and gender of each Pentecostal believer.

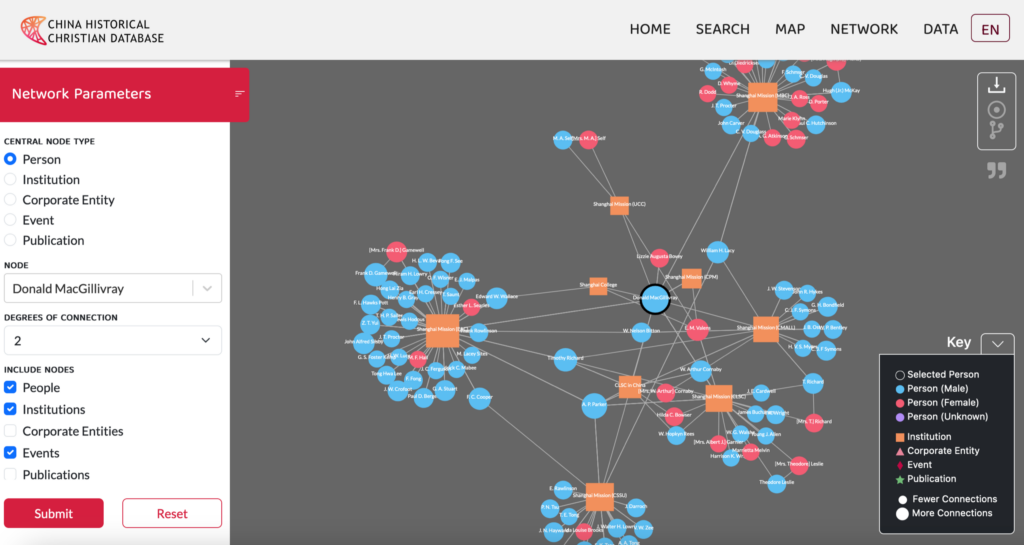

The result produced 4,905 different people, ministries, and locations which were tied together in a thick web of 33,355 relationships. This dense network was used to quantitatively illustrate that Pentecostals were heavily invested in building institutions, prioritizing education, working cooperatively with the government and other denominational bodies, and avoiding the city’s most densely populated areas.

All these findings cut across standard historical narratives that have treated the growth of global Pentecostalism as a sectarian, other-worldly phenomenon that is tied to urbanization and the displacements caused by the modern industrial economy.

If a relatively small sample could produce such new insights, what would become visible if someone looked beyond Hong Kong to all of China, included not just Pentecostal Christians but also Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox, and Chinese-initiated movements, and expanded the search from 35 to 400 years (1550-1950)?

At that scale, could a person see what role Christians and their institutions played in the formation of modern China? Daryl Ireland, the Associate Director at Boston University’s Center for Global Christianity and Mission (CGCM), was intrigued. Such a question aligned with the Center’s research focus and overlapped with his own expertise. Ireland, Mayfield, and Menegon agreed to expand the original project into the China Historical Christian Database (CHCD), making it an initiative of the CGCM in 2018.

Since that time, the CHCD has become the largest repository of information on Christianity in China ever assembled. It is a global effort. Partnering institutions and scholars from around the world are finding and inputting data. Since the initial launch of the CHCD in July 2022, for example, over 150 scholars and students on four continents have joined the effort to record where every Christian church, school, hospital, orphanage, publishing house, and the like were located in China, and helped identify who worked inside them, whether they were foreigners or Chinese.

The result is a tool that is growing in power. Its limitations are primarily those of the user’s imagination. Some people are using the data to study major missiological issues. For instance, women tended to be less mobile than men, so their social networks were generally smaller. Was that an evangelistic handicap or did their concentrated number of friendships prove to be stronger and more durable than men’s many but possibly fleeting relationships? The social networks of men and women in China may help us better understand the spread of the gospel.

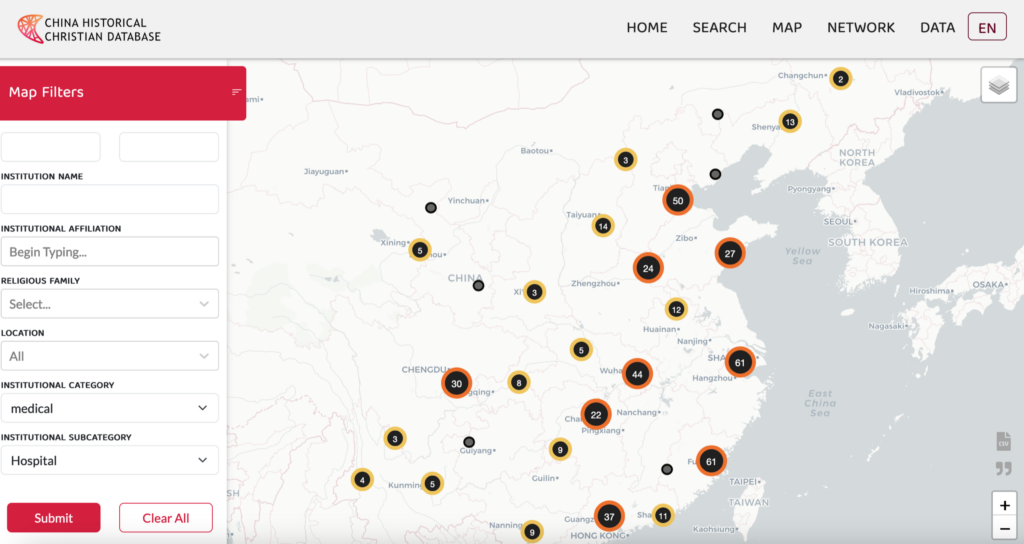

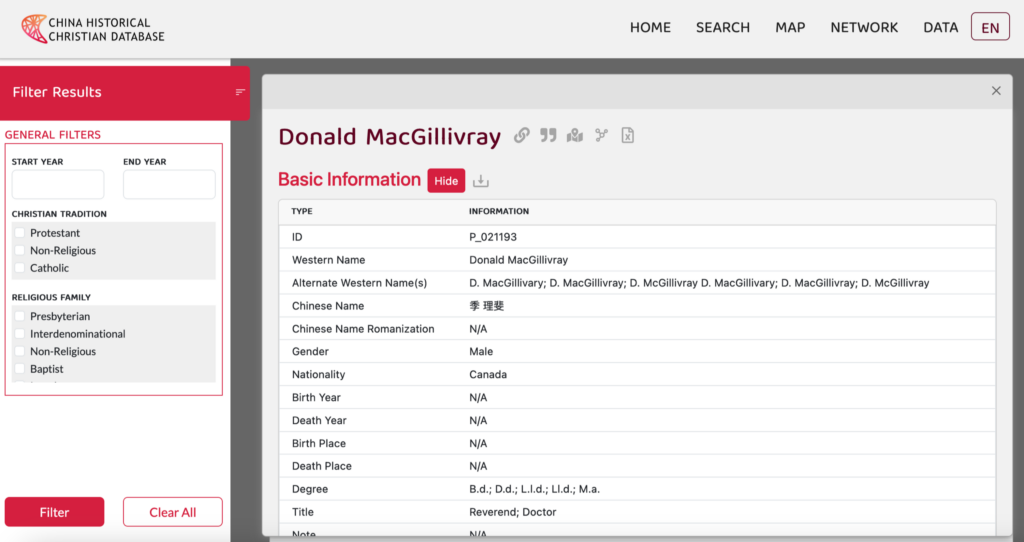

Others use the database more specifically. How many Roman Catholic hospitals were in Guangdong Province, and where were they located? What was the Chinese name of Donald MacGillivray, and who was part of his social network? Did the Russian Orthodox operate any schools? Which missions were active in Kaifeng between 1860 and 1911? Depending on your interests and skills, the CHCD offers a rich store house for uncovering China’s Christian past.

The Center for Global Christianity and Mission just released the second version of the CHCD. The data remains free to download, but most users find the web interface the easiest way to interact with the millions of data points. The CHCD 2.0 allows users to search for people, institutions, and organization; generate geographic and social network maps; or pull up statistical snapshots of mission organizations, such as the China Inland Mission. A fuller demonstration of what the CHCD can do and how to use the web interface can be viewed here.

The new release is an important milestone, but not the end. More still needs to be done. In the immediate future, the CHCD has five priorities:

- Find a better way to deliver the data to users in China. The obstacle is not a firewall obstructing usage, but the interaction between Chinese and American servers as they transfer large amounts of data.

- Enhance the Chinese language search engine. The CHCD functions in English as well as traditional and simplified Chinese; however, users currently searching in Chinese have inconsistent results.

- Expand the number of data points. The CHCD will soon drop new data on Franciscans and Dominicans in China, as well as large additional data sets on Orthodox and Chinese Protestant church leaders. However, since the project covers 400 years and over 400 Christian organizations, more can and needs to be done.

- Build new partnerships. The only way to improve and expand the data is through collaboration. If you want to get involved, please contact us.

- Fund the mission. The CHCD has received several grants in the past, including one from the United States’ National Endowment for the Humanities. However, all the grants have not exceeded the money individual donors combined have given. This project is not driven by the agendas of external funders, but exists because of the enthusiasm, determination, and cooperation of China enthusiasts and people around the world passionate about mission. We continue to rely on donations, and invite you to make a tax-deductible gift that will allow the CHCD to continue to grow.

At a time when the study of Christianity in China is becoming more difficult, the CHCD opens a new portal to explore China’s Christian past. The tool might be different than rummaging through a traditional archive, but by repackaging archival materials into an online tool it invites anyone to ask, “What could be discovered if…?”

Image credit: Courtesy of Chinese Christian Posters.

Daryl Ireland

Daryl Ireland is the Associate Director of the Center for Global Christianity and Mission, and the project manager of Chinese Christian Propaganda Posters. He focuses on the history of Christianity and mission in Asia. His study of 宋尚節 (John Sung), a Chinese revivalist whose itinerant ministry renewed the spiritual life of …View Full Bio

Alex Mayfield

Alex Mayfield is Assistant Professor of History at Asbury University, and he is one of the Co-Principal Investigators for the CHCD. His research interests include global Pentecostal and Charismatic movements, ecumenism, mission history in Asia, and the development of Chinese Christianity in the modern period. He is also dedicated to …View Full Bio

Eugenio Menegon

Eugenio Menegon teaches Chinese history and world history in the Department of History at Boston University, and was Director of the Boston University Center for the Study of Asia in 2012-2015. His interests include Chinese-Western relations in late imperial times, Chinese religions and Christianity in China, Chinese science, the intellectual …View Full Bio

Greta Rauch

Greta Rauch is a PhD student in the History Department at Boston University. She currently serves as the Project Manager for the CHCD. She received a bachelor’s degree in computer science with a supplemental major in Chinese from the University of Notre Dame. Her research interests include Catholicism in China …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.