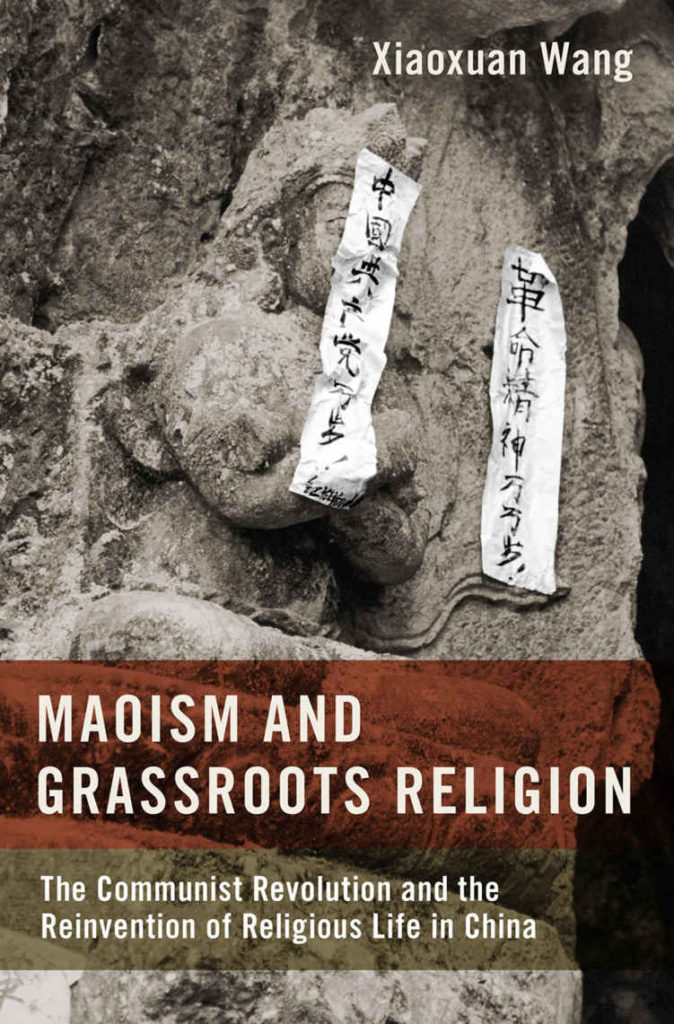

Xiaoxuan Wang, Maoism and Grassroots Religion: The Communist Revolution and the Reinvention of Religious Life in China. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020. Available on Amazon.

After touring China in the early 1980s, Christian radio personality Carl Lawrence wrote about the Christians he met during his travels. His book, titled The Church in China: How It Survives and Prospers Under Communism, featured a quote from a Chinese believer on the cover: “We not only survived, we grew!”

The story of the China church’s remarkable growth has been retold many times in the ensuing years through biographies and academic studies showing that the oppression under Mao, rather than stifling Christianity, actually contributed to its further development. Yet details of what really went on in the interaction between government and religious groups remain sketchy.

Xiaoxuan Wang notes:

It is curious, however, that to this day the Mao years remain the least studied period in the history of religion in modern China. The study of modern Chinese religion has burgeoned in the period since the end of Mao’s rule, yet most studies focus on the pre-1949 and post-1978 eras…. Very little has been written about certain facets of religious life from 1949 to 1978, such as any interactions concerning religion that occurred between local officials belonging to different levels of government, between officials and locals, or between religious and non-religious people. (p. 3)

Wang’s study stands out in two respects. His careful use of interviews, historical records, and statistics provides a systematic treatment of the interplay between political and religious developments in a specific locale. Secondly, by looking across the religious spectrum, Wang distinguishes the diverse responses of different religious communities. He shows convincingly how Mao’s policies inadvertently served to fuel the expansion of religion, and also explains the decline in traditional religious sects relative to Christianity, which grew at least fourfold during the same period.

A native of Rui’an County in Wenzhou, Wang brings to his research the advantage of fluency in the Wenzhou dialect, one of the most difficult in China, and a network of personal connections enabling access to local government archives, religious sites, and believers who experienced life under Mao. As a hotbed of religious activity both before and after Liberation, Wenzhou provides a unique case study of how, in the words of Wang, Maoism proved to be “destructively constructive,” ruthlessly demolishing traditional religious structures and practices while at the same time sparking innovation that would serve to redraw the religious landscape.

Wang begins with an overview of religious life before 1949, then turns to a discussion of how Communist forces coexisted with Wenzhou’s folk religionists, Buddhists, and Christians in the early years of Mao’s rule. Subsequent chapters alternate between folk and Buddhist communities, on the one hand, and Wenzhou Christians as they navigate the increasing attacks accompanying the Anti-Rightist Movement, Great Leap Forward, and Cultural Revolution. Wang follows up this treatment of religion under Mao with a look at how Maoism’s indelible imprint is still very much visible in contemporary Chinese religious life, as seen in the resurgence of both Buddhism and Christianity in Wenzhou and the ongoing struggles between religious communities and the state. Wang’s concluding chapter sums up the lasting effects of Maoism in terms of the revitalization of sacred spaces, seen today in the massive number of churches and temples that dot the Wenzhou landscape; the rearticulation of communal religion with local elites and politics; and the accession of localized Christianity, pointing to similar examples in other parts of China that also have large Christian populations.

A key element in Wang’s argument that Maoism has been both destructive and constructive to religion concerns the effects of land reform in the 1950s. These policies effectively disenfranchised traditional religious elites who relied on temple properties and village-wide festivals for income but had a lesser impact on the Protestant communities whose survival was not dependent upon maintaining specific locations or facilities. This flexibility allowed for the emergence of new forms of worship during periods of intense persecution. Wang also notes that “the hostile political environment actually reinforced communications and connections between Protestants in different places, pushing them to cooperate in order to ensure the survival of their communities.” (p. 182) As Wang points out, the relationship between land and religious expression was key to the reemergence of religion in the 1970s, when a large number of religious sites were rebuilt or reclaimed (with the newly reconstituted Three Self Patriotic Movement playing a major role in the reopening of churches), and it remains a point of contention today, as seen in the well-publicized cross removals and destruction of church buildings in Zhejiang Province beginning in 2014.

While studies of religion and government in China often focus specifically on religious directives or policies, Wang agrees with Gooassert and Palmer that an “ecological approach” is necessary to understand the contingent effect of the state’s political and economic agendas upon religious life. The example of land reform mentioned above illustrates this relationship. So does the case of the Catholic Church, which bore the political stigma of being branded “counterrevolutionary” and saw most its leaders imprisoned during the Mao years. Similarly Wang points out that the harsh treatment of Christians during the Great Leap Forward was more a function of strict production schedules than a direct attack on religious belief. On the other hand, factional Red Guard struggles and the fragmentation of government bureaucracy during the Cultural Revolution had the unintended consequence of providing social space amidst the chaos for religious activities.

The church that emerged in Wenzhou after the Mao years was remarkably cohesive and disproportionately influential as Wenzhou believers spread across China and beyond, doing business, planting churches, and becoming a resource to the greater Chinese church. Although it eventually become more divided due to denominationalism and theological differences, particularly in the debate over Arminianism and Calvinism, it continues to bear the unique marks of its formative experience under Mao, which brought both destruction and renewal.

Our thanks to Oxford University Press for supplying a copy of Maoism and Grassroots Religion: The Communist Revolution and the Reinvention of Religious Life in China, by Xiaoxuan Wang.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Brent Fulton

Brent Fulton is the founder of ChinaSource. Dr. Fulton served as the first president of ChinaSource until 2019. Prior to his service with ChinaSource, he served from 1995 to 2000 as the managing director of the Institute for Chinese Studies at Wheaton College. From 1987 to 1995 he served as founding …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.