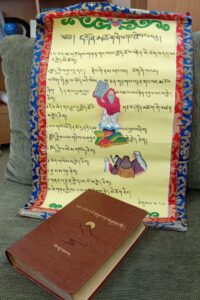

The mountains were starting to get snow-dressed, and the temperature was dropping but still comfortable while I walked between the shops, passing a small temple and some stupas on the way to the meeting. Under my arm, wrapped in my sweater, was a beautiful book with a light brown leather cover and golden edged papers, a Tibetan Bible, just received from the printer. A precious book and when opened it is written in a beautiful script, a script revered by Tibetan readers around the world. It is so special to have God’s Word in Tibetan, in my heart the thought came to me, “truly God speaks Tibetan.” I met with my Tibetan friend and gave him this precious Bible with two hands, and likewise it was received, then taken with respect to his lips with a kiss and held in an embrace close to his chest. His eyes were radiant with joy and great thankfulness. This Bible is the New Tibetan Bible (NTB), a work of God that started over 25 years ago. God has mobilized many to shoulder this amazing work to translate his Word into the modern literary Tibetan language.

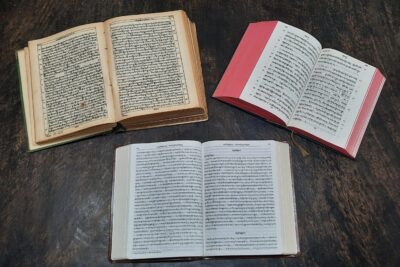

Although the NTB is a new translation, it stands on the legacy of God’s previous work of Tibetan Bible translation. The first Tibetan Bible translation was initiated around 1857 by the Moravian Church among the Ladakhi people who speak one dialect of Tibetan and was one of the few gateways to Tibet at that time. The Moravian translation was handwritten on precious paper, translated and worked on sheet by sheet. This first Tibetan Bible was printed in 1948 as a facsimile of the hand-written pages. Looking at this, you can still see how the writers adjusted their style to fit they sheets of papers they had been allotted in the Old Testament, while the New Testament was revised and kept in stylized handwriting. If you open Isaiah especially, you can see how the translator Joseph Gergan in Ladakh, the Little Tibet, adjusted his style several times and at the end used miniature writing to fit all in on his papers.

Joseph Gergan’s story can be read in God Spoke Tibetan by Alan Maberly. The journey from the 1850s for the Tibetan Bible brought multiple revisions and corrections with influence from different geographical areas and tried to accommodate the needs and the tension between classical literary Tibetan and the more easily understood spoken dialects. In 1968, the New Testament had been revised once again and this time printed with block print, while the Old Testament was kept as handwritten pages. This time the revision had been done with people from West Bengal, the area between Nepal and Bhutan and in that way became even more accepted and written in a style for a wider audience. This is the wonderful legacy of previous Tibetan Bible translations and the NTB translators are grateful to God for these works.

Looking at the Tibetan language from a big picture, spoken Tibetan exists in the many oral dialects found in the Central, Kham, and Amdo regions. Today there also exists a diaspora dialect among Tibetans living around the world. Literary Tibetan exists in its pre-1950 classical form as well as its modern literary form called “modern literary Tibetan.” Modern literary Tibetan is used to communicate among Tibetans cross-regionally, and can be seen on smart phones, internet web sites, and in newspapers and textbooks in Tibetan publishing. Modern literary Tibetan has been developed over many years by the Tibetan community as the written standard of communication across the Tibetan regions. In this way, Tibetans speak many local dialects but use the same literary script.

For this to make sense it is important to understand that Tibetan is a language functioning as two languages, a written and a spoken language. Literary Tibetan is following a classic style of writing, a letter-based writing in a fashion universal to the Tibetan dialects and languages. It means that you have a word spelled out in a classic way, as it should be written, but then you pronounce it for reading out loud in your local dialect.

The NTB has been produced by Tibetan translators using the standard grammar and word choices found in modern literary Tibetan. In Tibetan translation, there exists the tension between making something easy to read and keeping the text in standard literary Tibetan which demands a more formal language. Religious texts are expected to be formal and at a higher register. The NTB has been produced to the highest standards of quality through the process of drafting, multiple revisions, community testing, and consultant checking against the original languages. Testing has proven that for the narrative texts, the NTB can be understood by someone with a middle school level of Tibetan education. For those that prefer to listen to the NTB, at this time, audio Bibles have been completed for the New Testament and are available on the You Version app in the NTB Central, Amdo, and Kham reading dialects. The marvelous feat has made God’s word both beautiful and acceptable with a very high standard.

The translation of technical Biblical terms and ideas is a challenge in any language. For Tibetan, these challenges are amplified due to the stark contrast between the worldviews of Buddhism and Christian concepts. Throughout the work of the NTB, the Holy Spirit showed up time and time again by giving the translators “lexical surprises.” God gave words to express the Bible message, surprising words that were embedded in the language and waiting for discovery by the translators.

Words such as God, resurrection, cross, as well as eternal, salvation, devil, good news, sin, and judgement already existed in the language but were treasures hidden in plain sight, waiting for the team to discover them. Previous versions of translations were consulted, and when appropriate, terms were confirmed. The word confirmed for “God,” for example, “dkon-mchog,” means “the rarest being or object” or “the supreme being.” During years of research and community testing, it was found that the concept of “dkon-mchog” exists in the heart of Tibetans and pre-dates Buddhism. The concept of “dkon-mchog” has been in the Tibetan language for hundreds and hundreds of years. This was one of those “lexical surprises.”

Long ago, the Moravian translator Jaschke wrote in part, “To every Tibetan ‘dkon-mchog’ suggests the idea of some supernatural power, the existence of which he feels in his heart.” The NTB team confirmed that the concept of “dkon-mchog” is sacred, elevated, and known to all. Truly God’s grace has paved the way for his Word to come to the Tibetans in modern literary Tibetan.

We are very happy to be able to present to you this New Tibetan Bible. Challenges still exist for access, as many Tibetans live under pressure from family, society, and government rulers. Please pray with us for the New Tibetan Bible distribution, that the Word of God would be accessible to all Tibetans around the world, in diaspora or home, to study together and encourage each other with the Word of God. Truly, God still speaks Tibetan!

To purchase copies of the NTB, visit Central Aisa Publishing. Find audio Bibles read in the three main Tibetan dialects at the New Tibetan Bible website. We can also recommend reading Swimming Against the Current, Tibetan testimonies available in PDF books and print on request at TBWorld.net.

All images courtesy of the author.

Chris Gabriel

Chris Gabriel (pseudonym) is a dedicated networker and strategist deeply committed to serving God's people, especially those in the least reached regions. Over the past 25 years, he and his wife have tirelessly worked in Asia, empowering communities in various creative access areas. Today, their six grandchildren are doing their …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.