The Chinese diaspora has deep roots in many countries, with strong faith communities. Due to multiple political events over the past decade, Chinese immigration from both the mainland and Hong Kong have increased significantly. Churches are working to welcome newcomers and show Christ’s love to them, while at the same time reckon with the many views that old and new immigrants have of China. Later this month we’ll be publishing the spring 2024 issue of ChinaSource Quarterly. To give you a taste of what is in store, we’re publishing the lead article by Jeanne Wu.

The Global Chinese Diaspora Today: Overview and Mission Trends

by Jeanne Wu

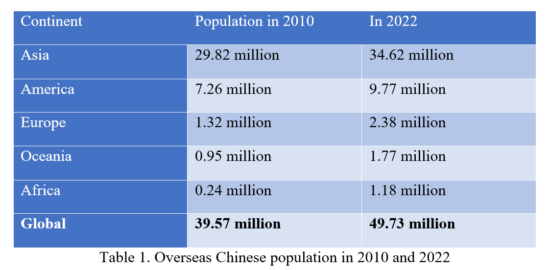

According to the 2022 Statistical Yearbook of the Overseas Community Affairs Council of Taiwan, overseas Chinese (海外華人, Haiwai Huaren), which includes ethnic Chinese (and their descendants) who emigrated from mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong number 49.7 million globally.1 The largest overseas Chinese population is in Asia (34.6 million), followed by the continent of America (about 9.8 million). Compared with the data in 2010, we can see growth in total numbers as well as in every continent (refer to Table 1). Both Europe (from 1.32 to 2.38 million) and Oceania (from 0.95 to 1.77 million) have nearly doubled in overseas Chinese population. However, the most significant growth has been observed in Africa, with an increase from 0.24 to 1.18 million—a surge of nearly 500% in just twelve years.

When studying the Chinese diaspora, we cannot overlook their relationship with their “homeland”—China. Political and economic conditions have made Chinese people move to other countries over the past several centuries. Traditionally, the Chinese diaspora was seen primarily as traders. For example, in the book Global Diaspora, Cohen categorizes the traditional Chinese diaspora as a “trade diaspora.”2

Following the “reform and opening up” of the People’s Republic of China in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the economy of China has grown rapidly, and the PRC has since been seen as a “twenty-first-century nation.”3 Consequently, more foreigners have begun to learn the Chinese language, and American high schools have even incorporated Chinese into their foreign language curricula. These changes have impacted the relationship between the Chinese diaspora and China, with some embracing their connection to China, while others have resisted.4

New Economic Settlers

Since the 1990s, China has intentionally invested in and sought allies with the majority world, including Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, collaborating in economic and political activities. Over the past ten years, since China started the One Belt, One Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013,5 the number of migrants from China has increased significantly in Africa and the Middle East. There are now about one million Chinese in Africa6 and more than half a million in the Middle East, most of whom live in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the UAE.7 The impact of the BRI is reflected by the growing Chinese population in Africa. The massive investment and infrastructure projects that China brought into Africa have also opened doors for Chinese laborers, professionals, and businessmen.8

I personally observed the growth of the Chinese community in the Middle East. When I first visited Egypt in 2014, there were only a few Chinese in Cairo. Now there is a district in Cairo that the local people call “Chinatown,” with many Chinese restaurants and shops located on the same street and all the business owners hailing from China. Some of them can speak decent Arabic.

Another example is the UAE. In 2004, “Dragon City,” the largest Chinese goods trading market in the Middle East, was opened in Dubai. The Chinese population in the International City district in Dubai has increased dramatically since 2013. It is reported that there are more than 200,000 Chinese in the UAE with most living in Dubai.9 Contract laborers, professionals, and businessmen from mainland China have built up their own community. As a result, the Chinese churches there also have grown.

“To Run Away”

Right after Thanksgiving 2023, The New York Times published an article reporting that “more than 24,000 Chinese citizens have been apprehended crossing into the United States from Mexico in the past year,” and “that is more than in the preceding 10 years combined, according to government data.”10 This news might be somewhat shocking considering the fact that China has been the world’s second largest economy and perceived as one of the rising great powers for the past ten years. Earlier in 2023, Christianity Today also reported the phenomenon of the current “run philosophy” (润学) among Chinese people, i.e., “To run away from China.” The article reflected on the opportunities and challenges this might bring to the Chinese church in the United States.11

A friend of mine became a believer when she studied in Europe and later returned to China and got married there. About five years ago, she and her family came to the States for studies but decided to seek asylum for religious reasons and stay in the US. Although they did not experience direct persecution, “It is simply hard to be Christians in China,” she commented to me.

Other friends of mine planted a Chinese congregation on the west coast of the US nearly ten years ago. A few months ago, I visited them right after their two-month long trip to China. It was their first homecoming after the pandemic. I asked them if they observed whether or not more Chinese people would like to immigrate to other countries. They told me that life in China is quite comfortable and convenient nowadays due to its advanced technology. For example, people can use WeChat Pay or Ali Pay to buy things both online and offline and hardly need to use cash in their daily lives. On the other hand, the three-year fight against the pandemic indeed left a toll on the economy of China, and they are still recovering from it. My friends’ conclusion was that those who are dissatisfied with the politics and the current government will try to leave for other countries.

Key Political Events and Mission Trends

We see clearly how the political situation in the Chinese “homeland” has impacted Chinese diaspora missions. Several key political decisions made by the Chinese government recently have caused a major shift affecting Chinese diaspora missions. The first one is the BRI in 2013. It has opened the door for Christian Chinese contractors and businessmen in South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa to become a potential mission force. One example is Business as Mission (BAM), which can serve in Creative-Access Nations (CAN) in South Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

The second significant political decision is the new Regulation on Religious Affairs, which was introduced in 2018. My previous research showed that China was the top destination for short-term mission teams from Chinese churches in the United States in the past.12 However, the door to China has been closed in recent years since the new Regulation on Religious Affairs began to be enforced in February 2018.13 Since then, a new wave of persecutions and missionary expulsions has taken place. Thus, many Chinese churches in the diaspora, including my home church in the US, have been searching for new fields to continue their mission mandate and have started to reach out to non-Chinese unreached people groups. For example, some Chinese churches in the States have begun to send out short-term mission teams to the Middle East to serve refugees in recent years. I personally have observed and researched this recent short-term mission movement by the Chinese diaspora to the Middle East.14

The third political move affecting the Chinese diaspora is the passing of the Hong Kong National Security Law in 2020, following the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests. Since then, Hong Kong has been perceived as losing its previous status. In response to this change, the UK initiated a new passport program for British Nationals Overseas (BNO) passport holders since January 2021. The outcome has been a massive Hong Kong emigration wave since 2021. Chinese churches in the UK and in several other Western countries have been seeking to respond to this influx of new Hong Kong immigrants ever since.15 All these political developments in China have significantly impacted the mission work of the Chinese diaspora.

We might arguably add a fourth and fifth events related to geopolitics: The global pandemic and the recent Taiwan-China tension. The COVID-19 global pandemic during 2020–2022 originated in China and led to the closing of China’s border for three years. In addition to religious restrictions, China being physically closed made the Chinese diaspora mission to China nearly impossible. As a result, there was a shift in the mission strategy and destinations of Chinese diaspora churches.16 The global pandemic also exacerbated the mistrust between China and the US, straining relations.

Furthermore, the recent increase in tension between Taiwan and China has impacted the flow of immigrants and has caused divisions among overseas Chinese communities. Historically, the 1995–1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis (during the year of the first presidential election in Taiwan) caused a large wave of emigration from Taiwan. A similar scenario occurred in 2023 before the 2024 presidential election in Taiwan but on a smaller scale. With the newly elected Taiwan president Lai and his pro-sovereignty party, this tension may continue in the coming years.

Evaluation and Reflections

Missiologists are still observing and evaluating the effects and outcomes of China’s rise and the related geopolitical changes. China’s One Belt One Road Initiative (BRI) has opened doors for Chinese Christians to enter so-called Creative Access Nations. More Chinese Christians are responding to the call of the Great Commission and “China’s Mission” (宣教的中國). However, BRI could be a double-edged sword since locals might feel as though the Chinese are taking advantage of poorer countries by developing their infrastructure in exchange for their natural resources, resembling a new form of colonialism. Chinese Christians should be cautious about utilizing the economic and political power of China as a means of mission, lest they might be prone to repeat the same mistakes that Western missionaries made during the colonial era.

On the other hand, while the new religious law in China has closed many doors of mission to China for cross-cultural kingdom workers, it also has forced mission organizations to rethink strategically about missions to China. Moreover, it has stimulated many Chinese Christians in diaspora to look further afield and reach beyond their own kinsmen.17 In addition, the recent exodus of Hong Kong Chinese has infused new life into the Chinese churches in diaspora and inspires a new movement of “mission through Chinese diaspora” among Chinese churches in the UK, Canada, and other Western countries.18 In all kinds of circumstances, the Lord is working.

Conclusion

There is a time for everything (Ecclesiastes 3:1). Our Lord is the lord of history, and everything happens according to his plan. The recent political developments in and related to China have impacted the movement and dynamics of the global Chinese diaspora. They have closed some doors for mission while opening others. Although there are uncertainties and possibly apprehension about the future, we have also seen opportunities opening at the same time, and these are not without their challenges. As Paul exhorts us, “Preach the word; be ready in season and out of season” (2 Timothy 4:2). May we be faithful and respond to the mission that the Lord entrusts to us.

To get the entire Quarterly delivered to your email inbox, be sure to subscribe!

Endnotes

- 2022 Statistical Yearbook of the Overseas Community Affairs Council of Taiwan, Overseas Community Affairs Council of ROC, accessed February 15, 2024, https://www.ocac.gov.tw/OCAC/Pages/VDetail.aspx?nodeid=30&pid=313.

- Robin Cohen, Global Diasporas: An Introduction. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

- Fred E. Jandt, An Introduction to Intercultural Communication: Identities in a Global Community,6th ed. (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2007), 87, 93.

- David Parker, “Going with the Flow?: Reflections on Recent Chinese Diaspora Studies,” Diaspora 14, no. 2/3 (2009): 416-17.

- “The Belt and Road Initiative,” Chinese State website, accessed February 15, 2024, http://english.www.gov.cn/beltAndRoad/.

- 周海金, 〈在非华人生存状况及其与当地族群关系〉,《侨务工作研究》, no. 2 (2014), accessed February 15, 2024, http://qwgzyj.gqb.gov.cn/hwzh/177/2453.shtml.

- 〈蓝皮书:阿联酋是中东地区中国移民增长最快的国家〉, China News, January 6, 2017, accessed February 15, 2024, http://www.chinanews.com.cn/m/hr/2017/01-06/8116463.shtml.

- See Michael Hicks, “China and Africa—An Introduction,” ChinaSource Quarterly, Autumn 2019, accessed February 15, 2024, https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/articles/china-and-africa-an-introduction/.

- See note 7 above.

- Eileen Sullivan, “Growing Numbers of Chinese Migrants Are Crossing the Southern Border,” New York Times, November 24, 2023, accessed February 15, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/24/us/politics/china-migrants-us-border.html.

- Sean Cheng, “The ‘Route Runners’ Are Coming to America. Are Chinese Churches Ready?” Christianity Today, May 3, 2023, accessed February 15, 2024, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2023/april-web-only/fleeing-china-immigration-chinese-church-mission.html.

- Jeanne Wu, Mission through Diaspora: The Case of the Chinese Church in the USA (Carlile, UK: Langham Monographs, 2016), 121–126.

- Regulation on Religious Affairs (2017 Revision), accessed February 15, 2024, https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/en/religious-affairs-regulations-2017/.

- Jeanne Wu, “Humanitarian Tours as Short-Term Mission: A New Trend in a Time of Middle Eastern Refugee Crisis,” Journal of EMS (Vol. 1 No. 1 2021), 65-82.

- Stefani McDade, “560 UK Churches Ready to Welcome Hong Kong Wave”, Christianity Today, Feb 19, 2021, accessed Nov 22, https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2021/february/hong-kong-ready-church-welcome-uk-migration.html

- For example, using online platform for training and holding conferences.

- Jeanne Wu, “Humanitarian Tours as Short-Term Mission: A New Trend in a Time of Middle Eastern Refugee Crisis”. Journal of Evangelical Missiological Society 1, no. 1 (2021): 72, 73, accessed February 15, 2024, https://www.journal-ems.org/index.php/home/issue/view/1.

- Isabel Ong, “First Study of Chinese Churches in Britain Examines Boom and Possible Bust,” Christianity Today, October 8, 2022, accessed February 15, 2024, https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2022/october/british-chinese-survey-hong-kong-churches.html.

Image credit: ChinaSource team.

Jeanne Wu

Jeanne Wu, PhD (TEDS), has been involved in ministries and research related to the Chinese diaspora since 2003, including in Europe, the US, and recently the Middle East. She and her husband have served in the Middle East since 2015. Besides frontline ministry she is also active in researching, consulting, …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.