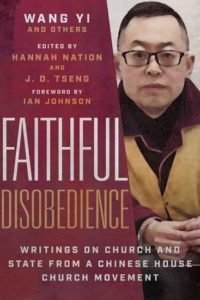

Faithful Disobedience: Writings on Church and State from a Chinese House Church Movement by Wang Yi and others, edited by Hannah Nation and J.D. Tseng. IVP Academic, 2022, 288 pages. ISBN-10 1514004135, ISBN-13 978-1514004135. Available from InterVarsity Press and Amazon.

The American historian David McCullogh has said, “History is who we are and why we are the way we are.” For the Chinese house church movement, a significant chapter of their history began on December 9, 2018. On that day the well-known and influential pastor of Early Rain Covenant Church (ERCC) in Chengdu, Wang Yi, was arrested, detained, and then a year later convicted and sentenced to a nine-year prison sentence, which he is currently serving.

The events of that day and what followed was not an unexplainable tangent, but rather an echo of many similar chapters in Chinese church history. It is the historical and theological context preceding and surrounding Wang Yi that Hannah Nation and J. D. Tseng seek to bring to light in their edited collection, Faithful Disobedience: Writings on Church and State from a Chinese House Church Movement. In her introduction Nation expresses her motivation in compiling this book by saying, “To understand the political conflicts between church and state in China from the perspective of the churches involved, one must begin to study the theology they are writing and using to inform their decisions” (p. 3).

This book seeks to showcase the voice of a pastor who has cared deeply, written wisely, and been affected greatly by the governmental attempt to control religion in the Middle Kingdom. It’s a “theological outworking of a pastor concerned for his flock, who is writing or speaking to others as he answers questions for himself” (p. 10). Anyone willing to read Faithful Disobedience will be blessed to be one of the “others” to whom Wang Yi writes.

Summary

A collection of 22 essays, letters, sermons, and statements, Faithful Disobedience feels like walking through a well curated museum exhibition. An exhibition that ties various writings together to tell a unified story of where the house church movement came from, where it is going, and how it is going to get there. Wang Yi and his contemporaries are placed in the larger context of the modern house church movement, demonstrating that house churches in China are not a simple ecclesiological model nor are they an accidental response to persecution. The house church movement is a theologically convinced category of churches that seek to faithfully follow Jesus in “this world [that] by nature is against the gospel” (p. 156). Faithful Disobedience shows this in three parts.

Part I: Our House Church Manifesto

Most everyone familiar with Christianity in China will have a general understanding of the Three Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM), but will have little knowledge of its origin, history, doctrine, or authority. Part I of Faithful Disobedience fleshes out where the TSPM came from and why the house church movement grew out of protest against the government-sanctioned Protestant church. Jin Tianming does not mince words in saying, “Participation in the Three-Self is to acknowledge the government’s power as the head, and not Christ” (p. 33). While Sun Yi exposes the incredible irony of the TSPM, noting, “The so-called Three-Self system, which nominally promotes ‘self-governance, self-support, self-propagation’ cannot itself have ‘self-governance, self-support, self-propagation’” (p. 62). This phenomenon raises an essential ecclesiological question the house church movement is wrestling with, “What is necessary for a church to be a church?”

While indebted to the saints that stood faithful in the events following 1949 and 1957, Wang Yi and others want to build on the foundation that earlier house churches laid. In doing so he argues that this generation has the opportunity to do what previous generations didn’t, that is, “Utilize the entire gospel of the Bible to address the relationships between church and society, gospel and culture, faith and politics” (p. 92).

Part II: The Eschatological Church and the City

This section is comprised entirely of talks or sermons of Wang Yi that flesh out how this pastor understands the church from Scripture and experience. Even as we live out the church’s role in this world, we long for the return of our king and his perfected kingdom. As we wait, “The church has a mission to let the world know who the church is” (p. 202). Ephesians 3:10 is to ring true in times of peace and persecution alike. Wang Yi pleads with his congregation to not forsake the role they have been given nor to lament the context in which they are to carry out that role. He does this with a jarring image, telling his people that as Christians, “You are a group of master ballet dancers performing at a landfill. And this is the meaning of the landfill—that although you will be deemed lunatics by those who stay near it, because of you, the landfill has become an image of the new heaven and the new earth” (p. 170). As Christians take part in this dance, the church will inevitably face countless trials, the greatest of which is to whom will the church pledge ultimate allegiance in worship. “The greatest worship battle the church has to face is not what songs we should sing during worship services. Rather, it is an age-old battle between the sovereignty of Christ and the sovereignty of the state in worship” (p. 186). It is an unsettling question for any church to ask of itself: who is the church’s ultimate choreographer—savior or state?

Part III: Arrest and the Way of the Cross

The final part of Faithful Disobedience contains, among other chapters, the letter that was widely disseminated after Wang Yi had been detained by authorities for 48 hours in December 2018, “My Declaration of Faithful Disobedience.” The purpose of this letter and part III is not to heroize Wang Yi or other house church leaders that have suffered persecution, but rather to paint a picture of a faithful God who is calling his people to live for another world while facing the effects of this one. As Wang Yi wrote, “The goal of disobedience is not to change the world but to testify about another world” (p. 223). Hatred of Christ, his kingdom, and his people will mark the age of the church, and yet, like Wang Yi we do not lose hope because through Christ our kingdom is not of this world. The encouragement of Li Yingqiang, the last elder of ERCC to be arrested, is true for anyone who claims the name of Christ, “May you welcome, filled with hope, the even heavier cross and more difficult lives that lie ahead of you” (p. 230). The cost of following Christ is great, but the crown that comes later is worth every cross he may give us to bear.

Reflection

Faithful Disobedience is a book that not only clarifies so much about Chinese church history and the current reality of persecution. It also does exactly what its editors hoped for, that is, uncover the biblical and theological convictions of the pastors and churches that are shaping the modern history of the Chinese church. Their theology is practical without being pragmatic, it is a theology that is rooted in Scripture and historic reformed soteriology and yet applied to every aspect of a hostile culture. This is something that, by their own admission, the house church movement needed to develop just as the Communist Party has developed, saying, “The position of the fundamentalists after 1949 [was] to uphold their soteriology but not touch on ecclesiology, views on the kingdom, or their intrinsic conflict between Christianity and communism” (p. 41).

This developing ecclesiology was perhaps the most surprising theme running through the various writings in Faithful Disobedience. While examining the history of house churches Jin Tianming notes, “In the past house churches suffered for the right to individual belief; today’s house church must persevere in suffering to build up the church” (p. 35). Persecution is not merely an opportunity for the faith of one to shine, but for the church to corporately stand firm and display the manifold wisdom of God to a watching world.

In a similar way, the refusal to join the TSPM is not a decision that each house church makes out of convenience or pragmatism. Their decision to reject the alluring benefits of coming under the banner of the TSPM goes right to the essential questions of what a church is and what a church is called to do. Sun Yi succinctly argues, “For the sake of our beliefs, we should not unite with an official organization which is not, by nature, a church” (p. 55). While congregations within the TSPM most certainly have Christians as some of its members, by its very nature the TSPM is not a church. As Jin Tianming plainly argues, “Participation in the Three-Self is to acknowledge the government’s power as the head, and not Christ” (p. 33). With Christ dethroned as Lord over the church, the TSPM has the self-appointed authority to also usurp the essential nature of a biblical church’s authority in matters of discipline and doctrine. In doing so the TSPM placed itself in authority over and in each of its churches, a concession house churches are biblically unwilling to make.

In the absence of suffering or persecution, a church can be tricked into the illusion that ecclesiology really doesn’t matter. For those churches, the pastors in Faithful Disobedience can serve as a prophetic warning to pay attention to the good gift of ecclesiology that Jesus intends for his church. I remember my own church being visited by the authorities and forced to scatter. While no one was arrested, we knew what our duty as a church was. While not ideal, we split into smaller churches because, like ERCC, “Under no circumstances will we stop or give up on gathering publicly, especially the corporate worship of believers on Sunday” (p. 216). The need for a robustly biblical ecclesiology is most urgently felt when the church is most acutely threatened. Faithful Disobedience, if nothing else, should strengthen our resolve to take great care of what Christ gave his life for: his church.

Conclusion

I pray the weight and value of the writings that make up Faithful Disobedience will be felt and realized by an increasingly large segment of the evangelical world. Through the persecution of this ordinary pastor and his church, we see a commitment to Scripture, a love for God, and a willingness to sacrifice that strengthens our resolve to do the same. Persecution will look different throughout the world, but regardless of where Jesus establishes his church, opposition will follow. We would rightly join with the Western China Presbytery and pray, “Through this storm, may the Lord’s church be a city set on a hill that is built firmly on the rock, a lamp on a stand that shines light into darkness” (p. 235).

Our thanks to InterVarsity Press for providing a copy of Faithful Disobedience: Writings on Church and State from a Chinese House Church Movement by Wang Yi and others, edited by Hannah Nation and J.D. Tseng, for this review.

Editor’s note: This post was updated on February 13, 2023 to correct an error regarding the length of Want Yi’s sentence.

Image credit: Congerdesign via Pixabay.

Noah Samuels

Noah Samuels (pseudonym) has lived in China for over a decade pastoring and working alongside local churches. View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.