I was recently asked to share a Christian devotional at a Chinese New Year party. In Chinese culture, each year is identified with an animal of the Chinese zodiac, and because this is the year of the dragon, an American friend suggested taking as my theme “slaying the dragon.”

To Westerners, this sounds perfectly reasonable. We think of dragons as evil creatures that destroy villages, imprison princesses, and hoard gold. Of course, this image of the malevolent dragon finds its ultimate source in the Garden of Eden, where a crafty serpent led all of humanity into ruin. The Bible explicitly identifies him as a dragon:

And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him (Revelation 12:9).

Then Jesus, that heavenly knight, came to earth, slayed the dragon, and saved his bride. As my pastor likes to say, the gospel can be summed up in one phrase: “Kill the dragon, get the girl.”

But to Chinese ears, the thought of slaying a dragon sounds repugnant. For in Chinese culture, dragons are benevolent beings that represent prosperity and power. They control rivers and seas and bring rain upon the earth. In fact, they are so revered that for thousands of years they have symbolized the emperor himself—the very mediator between man and Shangdi, the “Emperor on High.” They adorned the emperor’s robes, surrounded his throne, and guarded his palace walls.

And so, for many Chinese Christians, the year of the dragon is fraught with tension. Ought they to celebrate the dragon or to slay him? Some try to resolve this tension by asserting that the dragons of the East have nothing to do with those of the West (or of Scripture). The two were developed independently of each other and have their own unique characteristics. Thus, we can slay the one and celebrate the other without qualms. Others, however, suggest that the Chinese dragon is a manifestation of that ancient serpent, who has deceived the Chinese people into honoring it. A Chinese student of mine once told me about a dragon toy he used to play with as a child. One day, a Christian woman visited his home, and upon seeing the toy, abruptly took it away and destroyed it.

But I want to suggest that the Bible offers another solution to this tension, one which draws a connection between Western dragons and Eastern dragons without condemning the latter to perdition.

Dragons of Earth and Heaven

When we reflect on Israel’s exodus through the wilderness, we remember the many challenges they faced: no food, no water, hostile nations, a golden calf. But there is one formidable challenge we tend to forget—the horde of dragons:

And the people spoke against God and against Moses, “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we loathe this worthless food.” Then the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died. And the people came to Moses and said, “We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord and against you. Pray to the Lord, that he take away the serpents from us.” So Moses prayed for the people. And the Lord said to Moses, “Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.” So Moses made a bronze serpent and set it on a pole. And if a serpent bit anyone, he would look at the bronze serpent and live (Numbers 21:5–9).

The Hebrew word for “fiery serpent” in verse eight is one word—saraph, a substantive adjective derived from the verb “to burn.” The Hebrews called these serpents seraphim “burning [ones]” not because they were actually aflame, but because their venom burned (which, incidentally, may be where we got the idea of dragons spitting fire).1

But, of course, the Scriptures do not only locate these creatures on earth:

In the year that King Uzziah died I saw the Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up; and the train of his robe filled the temple. Above him stood the seraphim. Each had six wings: with two he covered his face, and with two he covered his feet, and with two he flew. And one called to another and said: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!” (Isaiah 6:1–3).

When Isaiah peaks into heaven, what does he find flying around the throne of God? Winged serpents. Holy dragons.

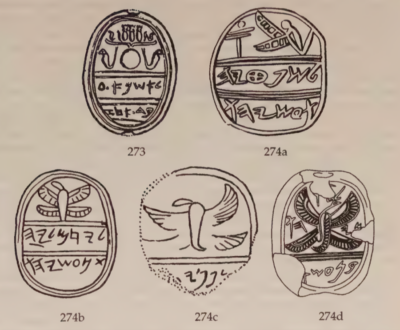

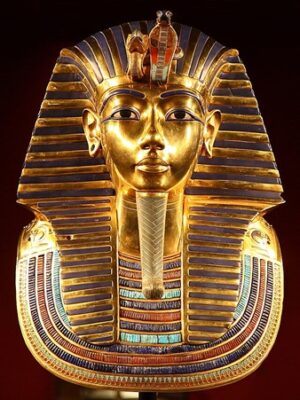

Incidentally, archaeologists have discovered many seals in Judah during the time of Isaiah which depict these creatures.2 And they are not limited to Israel. We find similar cobra-like creatures (called uraei) in Egyptian iconography, where they represent divine and imperial power. Sometimes they are depicted with wings and sometimes (like Chinese dragons) without. Egyptian emperors, like their Chinese counterparts, wore them atop their headdresses and etched them on their thrones. The Aztecs worshipped Quetzalcoatl, and the Mayans Kukulkan, both referring to the “Feathered Serpent” that represented kingship and the priesthood and from which Aztec high priests took their names. The Greeks similarly named their most revered priestess, the Oracle of Delphi (or the Pythia), after a divine primordial python that used to guard the holy site. Hindu priests lead ceremonies celebrating serpents in honor of the many-headed serpent king Shesha, upon which the supreme creator Vishnu sits.

On the left, the supreme Hindu creator god Vishnu sits upon Shesha, a multi-headed serpent deity that serves as his throne. On the right, an uraeus atop an Egyptian imperial headdress.

Is it a mere coincidence that so many civilizations have associated their supreme religious-political leaders with supernatural serpents? Or is it more likely that they, like Isaiah, caught a glimpse of the spiritual realm and saw creatures like these surrounding the throne of the heavenly Emperor himself?

The Fallen Dragon

When we recognize that the Bible has a category for benevolent dragons, the malevolent ones make much more sense. Returning to Eden, if Satan were merely a snake, then God’s curse on him defies logic:

Because you have done this, cursed are you above all livestock and above all beasts of the field; on your belly you shall go, and dust you shall eat all the days of your life (Genesis 3:14).

How is this a curse if the snake was already crawling on its belly? But if Satan was a seraph, a winged serpent, then it makes perfect sense. Flying in the presence of God, nearer to him than any creature, he attempted to usurp the holy throne and destroy his very image. As a result, his wings were clipped and he was cast down to the dust of the earth, where he will soon be crushed by the heal of the woman’s seed. There is a long scholarly tradition that identifies Satan as a seraph. We know for certain that cherubim dwelled in the Garden (Genesis 3:24), and so it takes little imagination to consider that a seraph may have as well.

The Good Dragon

And so, the Bible presents us with good reasons both for celebrating dragons and for slaying them. Insofar as they represent those unfallen throne guardians of heaven, they should be duly revered; and insofar as they represent that fallen seraph Satan, they should be crushed underfoot.

But the Scriptures add one more unexpected twist. When the Israelites were attacked by dragons in the wilderness, God did not save them as we might have expected. He did not command Moses to slay them like some valiant knight. He gave Moses a dragon of his own, one shining in radiant bronze, affixed to a pole. This dragon was not like those dragons of the West that only come to steal, kill, and destroy. This dragon came with healing in its wings.

What are we to make of this? About 1,400 years later, a respected Bible scholar named Nicodemus inquired of a certain wonder worker who taught deep mysteries about the kingdom of heaven. When he asked to peer into these mysteries, the man rebuked him. “If I have told you earthly things and you do not believe, how can you believe if I tell you heavenly things?” But in a moment of compassion, despite Nicodemus’s dullness, the man briefly lifted the veil:

No one has ascended into heaven except he who descended from heaven, the Son of Man. And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life (John 3:13–15).

The bronze serpent of Moses was but a symbol pointing to that true dragon, the Good Dragon, come down from heaven, who was nailed to a pole, lifted up, and placed at the right hand of God, where he waits to bestow true power and prosperity on all who call upon him.

Endnotes

- Richard Lederman, “What is the Biblical Flying Serpent?” TheTorah.com, accessed March 25, 2024, https://www.thetorah.com/article/what-is-the-biblical-flying-serpent.

- Othmar Keel and Christoph Uehlinger, Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1998), 272–277.

Image credits: Header, Ryan Moulton via UnSplash; Dragon throne in the Shenyang Imperial Palace, Gary Lee Todd, Ph.D., CC0, via Wikimedia Commons; Imperial seals, from Keel & Uehlinger, 1998, p. 275; image of Vishnu and Shesha, Daderot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons; an uraeus atop an Egyptian imperial headdress, Carsten Frenzl from Obernburg, Derutschland, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Brent Pinkall

Brent Pinkall is Lecturer of Rhetoric at New Saint Andrews College and author of Redeeming the Six Arts: A Christian Approach to Chinese Classical Education (Roman Roads Press, 2022). He has served the Chinese church for more than thirteen years, planting churches and promoting classical Christian education there.View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.