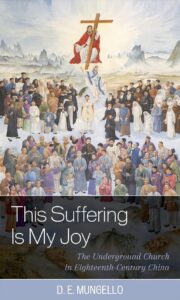

This Suffering is My Joy: The Underground Church in Eighteenth-Century China by D. E. Mungello. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2022, 186 pages. ISBN-10: 1538173972, ISBN-13: 978-1538173978. Available from Amazon.

Having looked at the structure and basic content of Mungello’s book in part one of the review, part two presents some of the more striking ideas discussed in the book. Four characteristics of China ministry following the Yongzheng Emperor’s 1724 proscription are highlighted, revealing some important lessons for China workers striving to serve faithfully in New Era China.

First, as Mungello makes quite clear, when the number of ordained expatriate priests and missionaries working in China decreased, Chinese Catholics stepped into the gap. In Sichuan this shift was undeniable: by 1800 there remained only four French missionaries serving alongside twenty-four Chinese priests.1 Despite substantial resistance from many within the church hierarchy to the ordination and training of Chinese believers for positions of authority, the nature of the crisis combined with the sincere faith and devotion of Chinese Catholics motivated a growing host of local believers who were willing to serve at great personal cost. As today’s expatriate China workers leave the country, can they do better at embracing and supporting local Christian leaders than their eighteenth-century predecessors?

Second, ministry under the proscription of the Yongzheng Emperor was indeed costly. Martyrdom was a reality for many priests—Chinese and foreign alike—and there are many Catholic saints drawn from the ranks of those who suffered for their brothers and sisters in China during these years. Even for those who escaped martyrdom, the cost could be high: Mungello records time and again the tremendous amount of time invested in preparing Chinese believers for ministry. Between travel, study, and ordination, young Chinese were often away from China for decades preparing for ministry in their homeland. Zheng Manuo Weixin, the first young Chinese man to receive full Jesuit formation, went overseas when he was 12, returning to the mainland 24 years later only to die of tuberculosis after just a few years of vocational service.2 In one case a young child was taken overseas to train for the priesthood and never returned: having failed to adjust to the rigorous religious training regimen in Italy, Jiangsu native Wu Lujue passed away in a house on the outskirts of Rome some 40 years after he left China for seminary.3 As conditions in China today become less conducive to ministry, are Christians inside and outside China prepared to make the investments necessary for faithful witness in the New Era?

Third, Mungello gives example after example of the ways in which local religious chose to take a more sympathetic approach to Chinese cultural habits and preferences than their European colleagues. Following the Chinese Rites Controversy, the Vatican’s rejection of the Jesuit’s more sympathetic view of Chinese ancestor veneration encouraged later generations of European missionaries to be more critical of Chinese cultural practices. As the number of European priests dwindled following the Yongzheng Emperor’s resultant proscription, the Chinese Catholics steadily moving into positions of authority took a far more flexible approach to contextualizing Catholic practice in China. For example, Chinese religious leaders were able to relax enforcement of the ban on ancestor veneration until the number of European priests once more began to exceed the number of Chinese Catholic clergy in the 1870s.4 Perhaps our current New Era may also provide an opportunity for more distinctly Chinese expressions of Christianity to emerge and draw more people into the church. It is also important to note that when the European missionaries began to return, they soon displaced Chinese Catholic leaders from their positions of authority, pulling the Chinese Catholic Church into closer unity with global Catholicism but increasing the church’s distance from local Chinese culture and society.5

Finally, Yongzheng’s 1724 ban was never absolute: from the very beginning at least some expatriate Catholics were allowed to remain in Beijing. Churches in Beijing continued to operate on and off throughout the ban, with the Lazarists even managing to provide formal training for local Catholics through a series of seminaries in and around Beijing.6 Over the next century, European priests lingered—though in decreasing number due to illness, expulsion, imprisonment, and martyrdom—often hiding in remote locations and travelling frequently so as to avoid detection and serve as wide a population of believers as possible. And despite the best efforts of the imperial state, Christianity not only endured, it grew. Mungello provides statistics from Sichuan as an example: following an initial period of decline due to persecution, the number of baptized converts grew from four thousand in 1756 to sixty thousand in 1815. Given China’s place in the world order today, it is very unlikely that they will completely ban all foreigners. There will always be exceptions—whether due to bureaucratic incompetence, local noncompliance, or China’s own self-interests. We can be confident that no matter how few the foreigners or how persecuted the flock, our God who makes the rocks cry out in testimony will ensure that his witness is never silenced, and his kingdom continues to advance.

This Suffering is My Joy provides a timely record of how God’s people in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries responded to government persecution and endured. This historical demonstration of the inability of the gates of hell to prevail against the church of Christ is a most welcome reminder for today’s China ministry community of God’s unending faithfulness.

Our thanks to Rowman & Littlefield Publishers for providing a copy of This Suffering is My Joy: The Underground Church in Eighteenth-Century China by D. E. Mungello for this review.

Endnotes

- Mungello, This Suffering, 114.

- Mungello, This Suffering, 111–12.

- Mungello, This Suffering, 37, 78.

- Mungello, This Suffering, 119–20, 133.

- Mungello, This Suffering, 127. For more on the Church’s late nineteenth-century drift away from Chinese cultural accommodation, see Henrietta Harrison, The Missionary’s Curse and Other Tales from a Chinese Catholic Village (University of California Press, 2013).

- Mungello, This Suffering, 126–27.

Image credit: Zhang Kaiyv via UnSplash.

Swells in the Middle Kingdom

"Swells in the Middle Kingdom" began his life in China as a student back in 1990 and still, to this day, is fascinated by the challenges and blessings of living and working in China.View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.