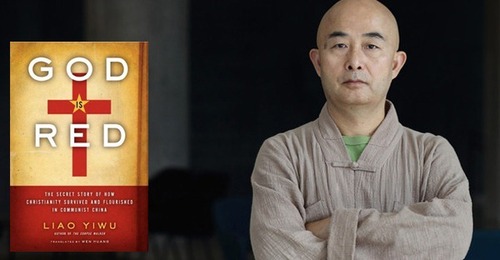

God is Red, by Liao Yiwu. HarperOne (September 13, 2011), 256 pp. ISBN-10: 0062078461 ISBN-13: 978-0062078469; hardcover. $16.25 at Amazon.com.

Reviewed by Kay Danielson

As a dissident writer, Liao Yiwu seems an unlikely author of a book about Christianity in China. His specialty of writing stories of the people on the edges of society, however, makes him an ideal candidate to relate the story Christianity in China. Like other such writers in China, he has been in and out of jail and his writings have been banned.

Liao’s first encounter with Christianity was in 1998 in Beijing when he met two young men who were active in an urban house church. Inspired by the courage of these believers, he decided he wanted to learn more about Christianity in China. Since he had come of age under the Maoist education system, his notions of Christianity were decidedly negative. Sensing the gap between what he had seen in the church in Beijing and what he had been taught, he set out for Yunnan Province in search of Christians to interview.

In the introduction to the book, the translator describes what Liao found: “In those ethnic enclaves, impoverished by isolation and largely neglected by modernization Liao stumbled upon a vibrant Christian community that had sprung from the work of Western missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” (p. x)

More broadly the book is (again, as the translator notes), an exploration of “the broader issue of spirituality in China in the post-Mao era, when the widespread loss of faith in Communism, as well as rampant corruption and greed resulting from the country’s relentless push for modernization have created a faith crisis.” (p. xii) As with everything else about China, the picture that emerges is complex:

Some stories, while unique and colorful, typify the experiences of ordinary Chinese Christians and shed light on the social and political controversies that envelop and at times overshadow the issue of Christian faith in China today. Other pieces capture the dark years of the Mao era, when the claws of political persecution left no place untouched in China and when thousands of Christians, and numberless others besides, were tortured and murdered. (p. xiii)

There are stories of horrendous and senseless persecution during the Great Leap Forward (1950’s) and Cultural Revolution (1960’s and 1970’s) as the government tried to rid Chinese society of any competing beliefs and ideologies. We learn about the persecution and eventual execution of Wang Mingzhi, the only Chinese martyr to have a monument in Westminster Abbey in London. His crime was being an “incorrigible counter-revolutionary.” Liao interviews Wang Mingzhi’s son and asks him: “Do you feel bitter about the past?” The reply: “No, I don’t feel bitter.” As Christians, we forgive the sinner and move on to the future. We are grateful for what we have today.” (p. 115) He then goes on to tell Liao that when his father died there were almost 3000 believers in the county and now there are 30,000.

There are stories of persistence and perseverance against the pettiness of bureaucrats after the persecution eased in the 1980’s and 1990’s. He introduces us to a 100-year old nun who survived the persecution and now spends her days relentlessly “pestering” the government to return to the church property and assets that had been seized in the 1960’s. We also meet doctors who give up their practices in the cities to work as medical missionaries in the remote mountain valleys of Yunnan, where there is little access to medical care. Local officials, fearing that they have ulterior motives and thinking that the Communist Party should have a monopoly on serving the people eventually ban their work.

There are stories of an emerging divide in the urban churches over whether or not to be politically engaged to push for change or to function quietly (and gratefully) in the expanding spaces. In Beijing he interviews a young convert and engages him in a discussion of the participation of Christian intellectuals in promoting political change. The young man responds: “People in your age group are too political. You guys are too interested in politics.” (p. 222). He then goes on: “There are a lot of talented intellectuals within government churches too. Some people choose to be outspoken, and others choose to be low-key. Some want to fight the political fight, and others want to stay away from politics.” (p. 223)

Finally, there are stories of missionaries who brought the gospel to remote towns and villages, building hospitals, orphanages, and Bible schools. Nearly everyone interviewed makes some reference to foreign missionaries. We learn of Jessie McDonald, a Canadian missionary doctor who is thought to have been the last foreign missionary to leave China in 1951, and of Catholics who labored among Tibetans in Cizhong. The significance of their contribution is brought home in the Acknowledgements section at the back of the book where there is a list of the foreign missionaries who worked in the region. In many ways, this book is a story of their legacies.

Shortly after I read this book, I read the book Mission Impossible: The Unreached Nosu on China’s Frontier by Ralph Covell. In it he relates the story of the missionary efforts he was involved with among the Nosu (Yi) people of southern Sichuan in the 1940’s. In many ways God is Red is a sequel to Covell’s book, as it tells the story of what happened to the church after the missionaries left.

On a visit back to China years later, he recounts visiting a small church in Sichuan and being asked by a local pastor his impressions of the area. Covell replied:

I expressed to him my disappointment over what I had seen small buildings, relatively few worshippers, a rather old congregation, and an infirm pastor. He quickly asked me, “But isn’t it wonderful that they even survived, that they are still there?” I had to agree with him. My attitude was not right praise was far more fitting than complaint. (Location 5998, Kindle version)

As we read God is Red, we also need to keep in mind this attitude correction that Covell talks about. Do we read these stories and find ourselves becoming primarily angry at the system that produced the persecution and suffering or primarily praising God for the perseverance and sustaining grace that was (and is) granted and for the explosive growth of the Church in China?

In an email to friends Liao spells out why he wrote the book: “I have the responsibility to help the world understand the true spirit of China, which will outlast the current totalitarian government.” (p. xiv) In one sense this book is that story, but even though he, as a non-believer, does not (yet) realize it, it is so much more. It is the story of the power of the gospel to change hearts. It is the story of sustaining grace. It is the story of revival. It is the story of China being filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord.

Reference:

Covell, Ralph, Mission Impossible: The Unreached Nosu on China’s Frontier (Pasadena: Hope Publishing), 1993.

Photo Credit: Sunset Church 02 by arbyreed, on Flickr