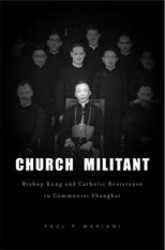

Church Militant: Bishop Kung and Catholic Resistance in Communist Shanghai by Paul P. Mariani. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (Nov. 23, 2011), ISBN-10: 0674061535; ISBN-13: 978-0674061538; 310 pages, kindle edition, $23.99; hardback, $37.42 at Amazon.com.

Church Militant: Bishop Kung and Catholic Resistance in Communist Shanghai by Paul P. Mariani. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (Nov. 23, 2011), ISBN-10: 0674061535; ISBN-13: 978-0674061538; 310 pages, kindle edition, $23.99; hardback, $37.42 at Amazon.com.

Many Christians (especially from Protestant backgrounds), interested in church history in twentieth-century China, may be more familiar with leaders of the early house church movement such as Wang Mingdao and Watchman Nee, rather than with their Catholic counterparts such as the “underground church” bishop, Ignatius Kung Pinmei, the first Chinese bishop of Shanghai. These men, along with many others, spent long years in prisons and labor camps for refusing the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) demands that they join the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) for Protestants, or the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association (CCPA) for Catholics, which aim to control the activities of Christians and force them to sever foreign ties.

Paul Mariani, a Jesuit, in this book makes an essential contribution to the story of the Catholic Church in China during this period, through penetrating research which includes previously unreleased classified documents from the Shanghai Municipal Archives and his multifaceted treatment of this turbulent period from the points of view of the many actors involved. He provides a gripping narrative as the gradual but increasingly tension-filled showdown between the CCP and the Catholic Church in Shanghai unfolds, skillfully told by frequently interweaving the words of persons engulfed in the drama, taken from interviews and documents from both sides. Most striking of all, however, are the classified documents, clearly showing that the CCP did have specific, targeted plans to destroy the power, vitality and influence of the Catholic Church in Shanghai, despite its claim to respect freedom of religion.

In the introduction, Mariani sets the stage with an important historical overview of Catholic missions in China, drawing out key questions at stake in the conflict between church and state. He traces the church’s origins in Shanghai to the time of the great Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) and influential Chinese convert, Paul Xu Guangqi (1562-1633), who later became the Grand Secretary to the emperor. He then reviews the following four centuries, both the church’s momentous accomplishments, such as the successes of Ricci and the early Jesuits at winning the favor of emperors, to its calamitous setbacks, such as the Chinese Rites Controversy, the two Opium Wars, the Taiping Rebellion, and the Boxer Rebellion, all of which brought China and the West into conflict, often with devastating violence.

Despite the great damage to Christianity’s reputation, the church grew over the long term, mainly due to dedicated missionaries who won the loyalty of Chinese converts, and who, at least for a few decades, enjoyed the support of the Republican government (1912-1949), building many schools, hospitals, and other institutions in the early 20th century.

Chapter one focuses on Shanghai from 1949 to 1951. After founding the PRC in 1949, the CCP sought to eliminate any remaining potential opposition and began targeting foreign missionaries, then in the thousands, as “imperialists” and Chinese Christians as their “running dogs.”

The CCP proposed its “Three Self” principles—“self-governing, self-propagating, and self-financing”—in order to force religious groups to cut ties with foreign entities. This “independence” meant that Catholics would have to cut ties with the pope. For them, however, the pope’s role as head of the church on earth, established by Jesus Christ himself, is a non-negotiable point of Christian doctrine. Meanwhile, in 1950, Shanghai’s Catholics were given a gift for which they had longed when Ignatius Kung Pinmei was named bishop. As the author states it, “Shanghai Catholics were jubilant. They referred to him not as the bishop but as our bishop” (p. 43).

Under Kung’s leadership, a revival of Catholic faith took place. He worked tirelessly to build up the faith of his flock. His deep love for youth and their ardent love for him and zeal for their faith, led him to organize retreats, catechism classes, and strongly support a youth organization dedicated to study and leadership, called the Legion of Mary, a kind of Catholic “spiritual army.”[i]

In chapter two, Mariani details the CCP’s targeted attacks against the Legion of Mary, the Catholic Central Bureau (CCB), the central coordinating body for bishops, and the papal internuncio (diplomat), Archbishop Anthony Riberi, who had strongly opposed the Catholic “patriotic” movement. A major tactic of the CCP was to attack foreign priests and paint the church as a foreign entity, during a time of great anti-Western fervor.

The Legion of Mary became another target, predictably, because of the group’s name, military terminology (“Mary’s Army” in Chinese), and its clear identification of communism as an evil force. At one point, Bishop Kung, who had proclaimed himself to be an ardent lover of both his country and the church, felt torn between the choice to instruct Legion members to compromise with the authorities in order to spare them from prison, or to continue to urge them to resist. After a young Jesuit leader in the Legion was arrested, students were strengthened in their resolve to choose prison over registration, which in turn bolstered Bishop Kung’s decision not to compromise. For a time, the youth and the bishop stood together and the government backed down from its most serious threats. As a prudential move, the Legion decided to disband, and its members joined the less provocatively named catechism groups where they continued to be well-trained in the study of scripture and the Catholic faith.

In chapters three and four we read of increasing arrests and expulsions, especially of foreign missionaries and of the increasing resolve of Chinese church leaders and lay believers to resist. Bishop Kung, sensing trouble to come, led three hundred seminarians and directors, including Father Louis Jin Luxian, to a nearby basilica where they all “took an oath to Our Lady of Sheshan not to betray the church” (p. 138).

We also learn of the sad events of September 8, 1955, when the CCP launched its third “strike hard” campaign against the church and “hundreds, if not thousands” of police raided Catholic churches, seminaries, and households, and arrested Bishop Kung, Father Jin Luxian, over twenty other priests, and more than three hundred leading Chinese Catholics. In the ensuing days and months, Kung and the others were denounced in large public meetings designed to show the Catholic youth that their leaders had been defeated. In one such meeting, Kung is said to have been pressured to speak, and after a time he “raised his head and shouted ‘Long live Christ’ several times,” to which the students shouted “Long live the bishop,” twice before the soldiers raised their rifles and ordered them to be quiet (p. 154).

In the fifth chapter, we see the CCP dividing the church by turning as many priests and leaders as possible against Kung and writing in the People’s Daily, “What the Kung Pin-mei counter-revolutionary clique did had absolutely nothing at all to do with religious belief.” The party succeeded in getting many priests to denounce Bishop Kung and began to set up what Mariani describes as a “puppet church.”

In 1956 and 1957, Catholics who remained loyal to the pope and Bishop Kung adapted and became known as the “underground” church. They refused to recognize “puppet” bishop, Zhang Jiashu, and some began to pray in private homes, avoiding the parishes that were increasingly under CCPA control, or to worship only at masses offered by “loyal” priests. The Holy See recognized and approved the underground church, even extending to loyal priests some faculties usually reserved for bishops. In 1957, the CCPA was formed officially, and in 1958 it began to consecrate new bishops without Vatican approval, a practice that continues today remaining a primary point of conflict in Sino-Vatican relations in the post-Mao era of “Reform and Opening.”

Bishop Kung and those arrested with him were given a show-trial and received life sentences. In 1979, he was secretly named a cardinal by Pope John Paul II and was finally released from prison in 1985. Held under house arrest until 1988, his nephew, Joseph Kung, obtained permission to bring him to the United States. A year later, Kung flew to Rome and met Pope John Paul, received his Cardinal’s red hat and an “unprecedented eight-minute standing ovation” from the crowd at St. Peter’s Basilica. He died in Connecticut, in March, 2000, at the age of ninety-eight.

A most intriguing part of the book is the epilogue in which Mariani turns his discussion toward a comparison between Kung and the controversial Jin Luxian, who, after his release from nearly thirty years in prison, in 1984 became the “official” (i.e. government-approved) bishop of Shanghai, without Rome’s approval, possibly because “he felt the future of the church was in jeopardy; he was afraid the government might appoint an even more pro-Communist bishop” (Adam Minter, quoted in Mariani, p. 214). Jin emerges as a very complex man, having served with Kung and others during the 1950s, taken the oath with him at Sheshan, endured long years in prison, and yet later cooperated with the regime, in effect, to ensure the survival and growth of the Catholic Church in Shanghai. As is well known, Jin built many churches and Catholic institutions in Shanghai during the last thirty years and enjoyed the respect of government authorities. He had also been attacked by many, especially underground Catholics, and yet, says Mariani (writing before Jin’s death in 2013), “ironically, it is he who ensures their protection—for given his contact with the authorities, who else but Jin could act as the protector of the underground church?” By 2005, it was widely acknowledged, although apparently never officially declared, that Jin was among the majority of bishops now reconciled with Rome (p. 220).

The book concludes by recognizing that the fundamental issues dividing the Catholic Church in China, as well as causing the Chinese government and the Holy See to remain at an impasse, are still unresolved. For example, in July 2012, shortly after this book’s publication, Thaddeus Ma Daqin was installed as the bishop of Shanghai and, at his ordination mass, made a bold move by announcing his resignation from the CCPA and remains under house arrest today, unable to take up his duties as bishop. At the same time, underground and official Catholic communities today coexist in widely varying degrees of reconciliation or continuing separation, depending on location and circumstances.

The book, as stated above, is an essential contribution to the field. Mariani asks the right questions, his analysis considers various sides, and he presents the complexity of the church’s situation up to the present time, even while his primary sympathies—with Bishop Kung and the underground church—are clear. There are a few places in which he raises curious issues without providing enough detail. For example, he writes that after his release from prison Bishop (then Cardinal-elect) Kung

was beginning to make confused and cryptic statements. Was he making these statements of his own volition? Was the party putting words into his mouth? In either case, the fear was that Kung could too easily play into the hands of the CCP. These diehard Catholics wanted to preserve intact the memory of Kung’s heroic resistance. They did not want it sullied in any way by the complexity of the new situation or by the powerful forces arrayed against an exhausted old bishop (p. 215).

Although most readers will fully sympathize with Kung, this intriguing statement still causes one to wonder exactly what kinds of statements Kung was making and about possible explanations. On the whole, however, this outstanding book is recommended for any seeking a penetrating account of events and issues which are still pertinent to the ongoing trials of the Catholic Church in China today.

[i] Whereas some Protestant traditions tend to find Catholics’ loyalty to the Virgin Mary and groups dedicated to her to be unacceptable because they seem to rival the loyalty that is due to Christ alone, Catholics see no conflict, viewing Christ, who they worship as Lord and Savior and as one of the persons of God in the Holy Trinity, and his mother, who they honor for her complete obedience and steadfast maternal devotion to raising Jesus as Theotokos (the Mother of God), as being already perfectly united in obeying the will of God the Father. For them, to love and honor Mary is to love and serve Christ himself, for she always instructs believers as she did the servants at Cana to “do whatever He tells you” (John 2:5).

Photo Credit: St. Ignatius Cathedral by 待宵草 (Gino Zhang), on Flickr

John A. Lindblom

John A. Lindblom is currently pursuing a doctoral degree in World Religions and World Church at the University of Notre Dame. He holds an MA in China Studies from the UW Jackson School of International Studies and has spent several years working in mainland China where he was also involved with …View Full Bio