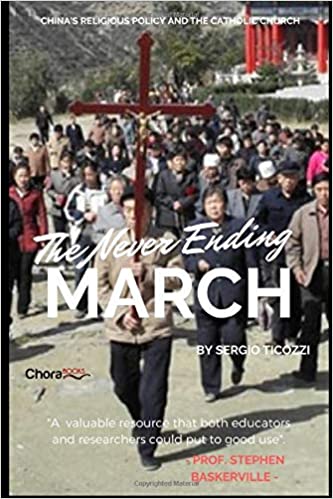

The Never Ending March: China’s Religious Policy and the Catholic Church by Sergio Ticozzi, preface by Stephen Baskerville. Hong Kong: Chorabooks, 2018, 183 pages.

Shortly after the provisional accord on the nomination of bishops in China was announced by the Vatican and Beijing, Chorabooks released The Never Ending March. Now, two years later, with the Sino-Vatican accord renewed, once again provisionally, once again in secret, and once again against a backdrop of slow progress and frequent setback, the title of Sergio Ticozzi’s book strikes the weary observer as all too accurate.

The author is a member of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions, also known as the PIME Fathers (based on the Latin name for their institute). The Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions is a missionary society founded in Italy in 1850. Father Ticozzi himself has lived in China for over 50 years. He currently serves as a Researcher and Project Director on staff at the Holy Spirit Study Centre, which is run by the Catholic Diocese of Hong Kong. He has written numerous articles, book chapters, and books on religion in China, the Catholic Church in China, and the Catholic Church in Hong Kong, in particular.

The first two chapters in this brief volume review the history of the Catholic Church in China since 1949. The third discusses the larger contemporary socio-political context in which the Church finds itself. The fourth provides a clear-eyed recapitulation and analysis of China’s current religious policy, especially as it relates to the Catholic Church in China. The final two chapters then treat the breakdown in relations between China and the Vatican since the rise of CCP leadership in China and subsequent attempts to establish dialogue.

Of these six chapters, two were articles previously published on the website of the Holy Spirit Study Centre, and an additional two were released in 2017 as articles in Tripod (鼎), its quarterly journal. To these were added the final two chapters. In discussing Sino-Vatican relations, they in turn flesh out a dimension of the circumstances of the Chinese Catholic Church that was only peripheral in the preceding four chapters.

Despite not being constructed as a continuous narrative at the outset, as a collection, these articles do combine to provide a detailed, yet thoughtful, discussion of the history and political circumstances of the Catholic Church in China. This includes a recounting of China’s religious policy under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) since 1949 and an examination of key precedents under the Qing Dynasty. In his crisp review of key documents and developments, Ticozzi provides an outline that is especially helpful for the newcomer who is not well versed in this history. Moreover, in his review of contemporary policy, he takes pains to explain what it actually entails in practice.

Ticozzi’s ability to tease out the actual thrust of Chinese religious policy is particularly valuable. The author is an experienced observer of the CCP who offers insight into the dynamics behind the policies he discusses. Overall, he notes that while there are a variety of voices within the Party, those that view religion as a problem to be managed and “solved” currently dominate the conversation.

Ticozzi’s treatment of relations between China and the Holy See begins with the Qing Dynasty and runs through the year of publication, 2018. He lays out the technical issues, the parties involved in the debate, and the concerns that hinder progress even where some parties keenly desire it. As he notes, on the Chinese side, while the Foreign Ministry desires diplomatic relations with the Vatican in order to further isolate Taiwan, the United Front (the Party’s arm for working with non-Communist groups in society) and the State Administration for Religious Affairs are the organs that directly control the life of the Catholic Church in China, and they are not interested in compromising their position.

Overall, Ticozzi provides an excellent summary of key developments that any commentator must know in order to understand the Chinese policy toward the Catholic Church, as well as how that has evolved over time. His commentary is brief and pointed. As one might expect given the composite nature of the book, he does not provide a grand framework for pulling together his observations. For the reader who would prefer a review of key developments without the distraction of an explicit grand narrative, this approach is welcome.

Nonetheless, it is clear that one key concern dominates Fr. Ticozzi’s work throughout: religious freedom in China, especially in light of the constraints and excessive regulation of the Catholic Church. While the mainstream academic community might view that concern as narrow or partisan, for those who share it—and there are many—that in fact makes his discussion extremely valuable.

We are grateful to Chora Books for providing a copy of The Never Ending March: China’s Religious Policy and the Catholic Church.

This review also appeared in the October 2020 issue of the Faith & Dialogue Newsletter, Issue 003 of the US–China Catholic Association.

Image credit: Christa Uymatiao via Flickr.

Michael Agliardo

Rev. Michael Agliardo, SJ, PhD is the executive director of the US–China Catholic Association. Fr. Michael Agliardo is a member of the Society of Jesus, a Catholic religious order more commonly known as “the Jesuits.” Early in his career as a Jesuit, he worked in campus ministry and taught theology at …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.