Non-Chinese who have become deeply invested in China usually have a clear memory of the moment when they became captivated by China and its culture. It is no different for my wife, Sandy, and me. On October 15, 1996, we had a life-changing moment that began our deep investment in China and its culture. In an orphanage in Guangdong Province, a 4½ month old baby girl was placed in our arms. That moment changed our new daughter’s life and our lives in many ways. And it was the moment Sandy and I became captivated by China and its culture.

Navigating Parenthood: Cultivating a Chinese Identity

Our journey into parenthood was very different than we planned. We desired to begin our family about three years into our marriage, but pregnancy didn’t happen. After three more years and being very sad on Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, we began to consider adoption. A neighbor mentioned an adoption agency that might be able to help us. When we met with the director of the agency, she mentioned the need for adoptive parents for baby girls in China. Sandy and I didn’t know much about China, had no Chinese friends, and almost never ate Chinese food. After careful consideration and prayer, we dove into the paperwork, got our passports, and embarked on the path to parenthood. Our preparation included reading Wild Swans, learning to use chopsticks, learning a few phrases in Mandarin, and delving into Chinese history. Nine months after initiating the adoption process, we made the long journey to Maoming, Guangdong where we went straight to an orphanage and had the daughter we had been matched with placed into our arms.

Adoption and Cultural Exploration: Shaping Family Identity

I was a high school math teacher and Sandy felt called to leave her job at Stanford University to be a full-time mother, so we moved from California to a much more affordable city, Lubbock, TX, just before our adoption. The agency director wisely told us that we would need to be intentional about helping our daughter establish her Chinese identity. The first Sunday after we returned from China, an American couple who had just returned from living in China spoke at our church. They mentioned a need for American families to befriend students from China studying at Texas Tech University. We saw that as a great opportunity for our daughter and us to learn about China and Chinese culture. Within a couple of weeks we were hosting a PhD student from China and his wife for dinner. We were grateful to learn from them as our friendship grew and as our daughter began growing up.

We moved to Dallas, TX a year and a half later and met more students from China at the University of Texas at Dallas. Living in Dallas also gave us the opportunity to enroll our daughter in a Saturday morning Chinese language school, which we thought would encourage her Chinese identity. But when we saw her squirming in her seat, struggling to keep up with the lessons, and not having an opportunity to speak Chinese at home as most of the other children did, we realized that it was not helpful. In fact, several parents told us that their children resented being forced to attend Chinese school, and it made them less attracted to Chinese culture. Our main objective was to facilitate our daughter’s connection with her cultural heritage and foster her Chinese identity, not to have her become fluent in the Chinese language. With this in mind, we made the decision to withdraw her from Chinese school.

A Growing Family of Love

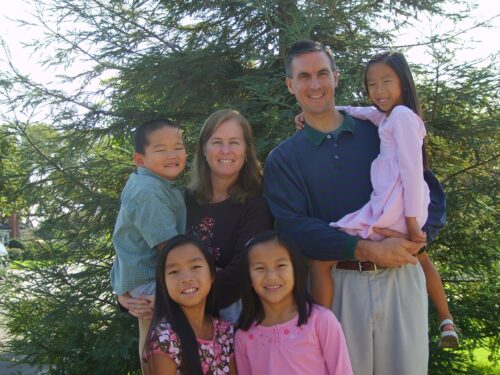

Sandy and I both came from rather large families and knew the benefits of having siblings, so we knew immediately that we wanted to adopt more children. We adopted a second daughter from China in 1998 when she was eight months old and a third daughter in 1999 when she was six months old. We missed our family in California, so in 2000 we moved back to Southern California and began to work full time for an organization that welcomes international students. Before moving, I went on the internet and found the area with the highest Asian population and moved to the San Gabriel Valley where our local schools are 60-75% Asian. After three girls, we found out that about 10% of adoptions in China were boys, so we adopted our son in 2003 when he was 13 months old.

Living in an area with a majority Chinese population has been a big help with immersing our children in Chinese culture. In addition to lots of time with Chinese students, including camping, hiking, eating, and just being together, and we asked them to teach calligraphy to our kids. We also started piano lessons for children when they were five years old, joined an Asian American church, ate tasty food from Guangdong and Shanghai restaurants in our neighborhood, and enjoyed celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival with mooncakes.

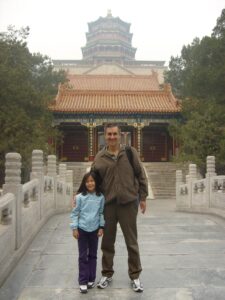

Another important factor in encouraging their Chinese identity was a decision to take each of our children to China on a special father-child trip when they were nine years old. We determined that, at that age, children remember experiences well. Instead of taking them back to their orphanages, about which they had no memories, I focused on Beijing. In Beijing we could visit Chinese friends whom we met when they were students and scholars in the US (海龟 hǎiguī)1 and learn about Chinese history and culture by visiting the Summer Palace, Forbidden City, Temple of Heaven, and other sites.

Shaping Identity: Memories, Experiences, Relationships, and Values

Now our children are not children any more. They range in age from 21 to 27. Sandy and I were captivated by China 27 years ago, but now we are aware that our investment in helping our children establish their Chinese identity has been successful. We have learned that a person’s identity is not determined by their appearance. Identity is determined by a person’s memories, experiences, relationships, and values.

One beneficial factor influencing their Chinese identity is where we live. A trip to a Chinese market in our neighborhood to buy dragon fruit or a family dinner of xiaolongbao at a nearby Shanghai-style restaurant have created cultural experiences that now seem normal to them. In fact, when we go to an American grocery store, our kids will comment about the lack of smells and say that it is too sterile!

A second beneficial factor is our intentional friendships with Chinese students and scholars and their families. The relationships between our family and Chinese friends have continued for more than 20 years, which has resulted in an infusion of Chinese values into our family, foremost of which is respect for parents and grandparents. That cannot be learned in a classroom or from a video.

We are grateful that our children have grown up to identify as Chinese. I am also grateful that Sandy and I have seen a change in our identity since we became captivated by China and its culture. The memories, experiences, relationships, and values that have developed inside of us have helped us establish a Chinese American identity!

Endnotes

Image credit: Andy Pearce.

Andy Pearce

Andy serves as Director of Church Partnerships for International Students, Inc. He has ten years experience as a high school math teacher and worked for four years as a textbook sales representative. Andy and his wife, Sandy, have welcomed Chinese scholars to California Institute of Technology for more than 20 …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.