Over the past over twenty years, migrant worker churches have grown significantly and become a large part of the church family in China. However, with the process of urbanization, over the past five years, migrant churches in first-tier cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, have not enjoyed advantageous environments for existence and development, and their size and influence has been shrinking. Like many other migrant worker pastors in first-tier cities, I have been serving full time at migrant churches for many years, and I hope that these churches will be able to break through the current dilemma and continue planting churches during this wave of urbanization.

This article is composed of three parts. The first part will summarize the situation of migrant workers in China; the second gives a brief introduction to the relationship between China’s urbanization and migrant worker churches. Finally, I will offer a few suggestions about how to multiply migrant churches in this new era.

Overview on Migrant Workers in China

According to statistics announced at the end of August 2021 by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), in 2020 the urbanization rate of the country’s permanent population reached 63.89%, and the number of cities hit 687.1

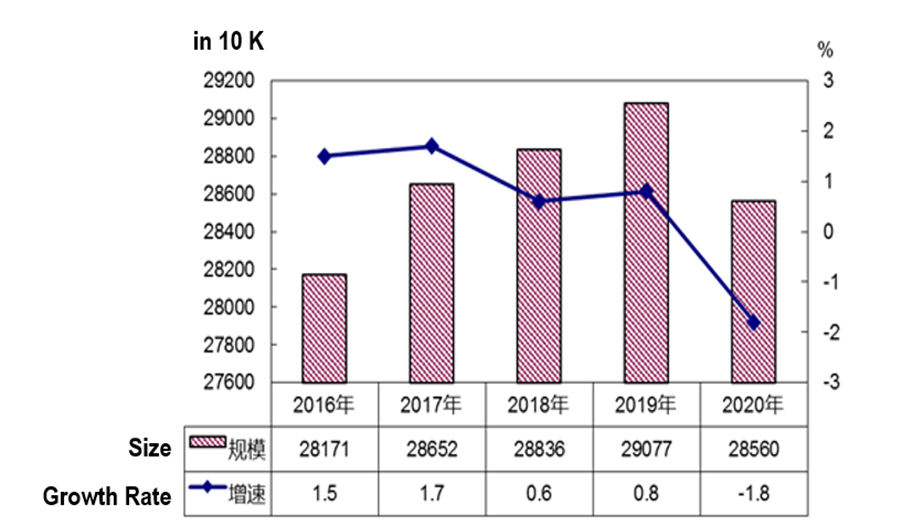

In April of 2021, The National Bureau of Statistics of China issued its “2020 Report on the Monitoring Survey of Migrant Workers.” According to this report, in 2020 there were 285.6 million migrant workers in China,2 equaling 98.2% of the previous year’s total. In comparison with the previous year, this is a decrease of 5.17 million and a drop by 1.8% (please refer to Chart 1 for details).3 The slow-down of migrant workers’ moving is one of the natural outcomes of a high rate of urbanization. More and more migrant workers can enjoy a stable life and work in cities, and this brings a positive impact on these migrant churches so they can keep growing and reaching out.

Chart 1 Migrant Workers’ Total Numbers (Size) and Growth Rate

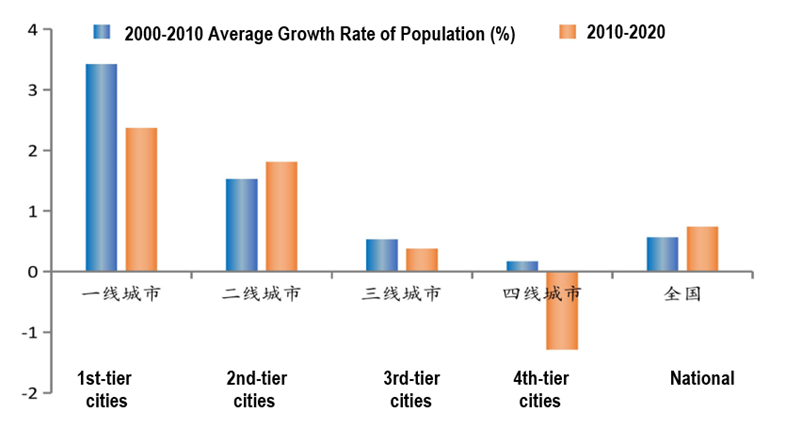

Taking a general look at the average growth rates of the national population in the periods of 2000–2010 and 2010–2020 (please refer to Chart 2), we may observe the following: the first-tier cities’ population remains concentrated but has a slowed-down growth rate; the second-tier cities keep having inflowing population and the growth rate is moving slightly upward; the third tier’s average growth rate is slightly below the national average; and the fourth tier is having a growth rate that is obviously lower than national average and a negative increase over the past ten years. This indicates that overall, the third- and fourth-tier cities’ population keeps decreasing.5

Chart 2 Average Growth Rate of Population in 1st–4th Tier Cities in 2000–2010 and 2010–2020

There are still about 280 million migrant workers, the majority of whom flow into the second- and third-tier cities. This provides us with some references in terms of locations where we should give priority for migrant worker churches’ planting. Over the next ten years, the focus of planting migrant churches should move from first-tier cities to those of second, third, and fourth tiers.

Relations between Urbanization and Migrant Worker Churches

China is going through rapid urbanization, with the urbanization rate increasing by about 1% each year.7 Urbanization, as a part of social transformation, brings us challenges and opportunities, and these affect churches as well. Village Christians move from rural areas to cities with economic concerns as their initial motive. Their internal desire for growth in faith, as well as problems and pressures they face in cities, push them to look for churches that can nurture and care for them spiritually.8 Under these circumstances, migrant churches in cities come into being.

Shining Gao states that urbanization is the process during which village populations move to the cities, resulting in more, and larger cities, and higher percentages of city population.9 In modern society, relatively concentrated population in cities, and the conveniences brought by advanced technology, also benefit the development of religions, including Christianity.

Hao Yuan also believes that the springing up of migrant churches is closely related to the population flow in China (migration movement).10 Benefiting from the revival of Christianity in villages, migrant worker churches are developing fast in cities. Since the mid-1990s, Christianity started to grow in villages in the provinces of Henan and Anhui, and it continues to grow in this period of urbanization, promoting the formation, development, and revival of migrant worker churches in cities.

Suggestions for Planting Migrant Worker Churches

In recent years, urbanization in China has not slowed down. The first-tier cities are growing in industry, drawing “high-end” enterprises and talents and, at the same time, sending migrant workers who were engaged in “low-end” industries back to villages under misleading policies. Migrant churches in the first-tier cities need great efforts to take a single step forward, and their sizes are shrinking gradually as those in low-end industries leave. Migrant workers and their churches are facing another migration; however, there are always opportunities in a crisis.

In 2018, the Chinese government announced a policy encouraging cities with populations under 3.5 million to grant migrant workers city household registrations. Some fast-developing provincial capitals (mainly those in second-tier cities) have started to absorb increased population to expand their size as migrants can live there more easily. This trend is going to become more and more obvious, and cities of third and fourth tiers will copy them. In addition, due to a series of advantageous policies, such as revitalizing villages, alleviating poverty through development, encouraging migrant workers to return for employment, and so on, more villagers now choose to stay in their hometowns to work and even to start their own businesses. In this case, there is still huge potential to continuously plant migrant churches in the cities or towns where migrant workers’ original household registrations are or in other second- to fourth-tier cities.

When talking about the value and meaning of church planting, Tim Keller gives the following suggestion:

The only way to be truly sure you are increasing the number of Christians in a town is to increase the number of churches. …The vigorous, continual planting of new congregations is the single most crucial strategy for 1) the numerical growth of the body of Christ in any city, and 2) the continual corporate renewal and revival of the existing churches in a city.11

Under the new wave of urbanization in China, pastors in migrant churches need to have “the perspective of the kingdom,” and keep planting vigorous churches with new concepts and new models. In order to multiply migrant worker churches, I suggest the following:

1. Take initiative instead of remaining passive.

Taking initiative means that leaders in migrant worker churches need be equipped with a sense of “foresight” and a vision for church planting, being able to comprehend the opportunities brought by migration. They must work out strategies and plans in advance, determine the beginning point of church planting among the migration in new first-, second-, third-, and fourth-tier cities, plant churches in new areas relying upon mature ministry workers who move there or with other church planting partners. Leaders of migrant worker churches should embrace a modern and transformative way of thinking, which is actually the power that pushes migrant churches to move on.

2. Grow in mobility instead of being satisfied with stability.

The current strategies of church planting that migrant worker churches use need be flexible. Wherever believers go, new churches must be planted. Pastors of migrant churches should break through the old thinking of “defending our own corner.” Instead, they are going out together with believers in the midst of the migration wave, guiding and encouraging mature believers—such as leaders among the believers, church planters, deacons, and so on—to embrace the vision and burden of church planting after they arrive in new cities. Even before these migrant workers leave for new cities, leaders can motivate them with a sense of mission, equipping them with spiritual responsibilities and tasks. While upon their arrival they are seeking a better life in cities, at the same time they are striving to live out the Lord Jesus’ great mission—to train disciples and to multiply churches.

3. Work in teams instead of as a one-man show.

Pastors and planters of migrant churches should value teamwork and cooperation while planting churches, including the cooperation among churches in neighboring cities, pastors of churches in cities, migrant workers, pastors of different migrant worker churches (this is particularly important), seminaries, and planted churches. Comprehensive cooperation can bring all sorts of resources together and draw out the best of them. Advanced networks of communication and transportation in modern society make this type of cooperation possible.

4. Develop a cycle of multiplication without gaps.

Dandelions are good at making use of the wind to complete their self-multiplication. Migrant churches should follow the way of the dandelions and plant churches of Christ everywhere. This is the so-called “Dandelion Pattern of Church Planting.”12 Migrant churches may borrow the pushing and pulling powers of the migration wave, having one or a couple of mature churches send eligible planters to establish churches in target cities and provide new churches with manpower, materials, and spiritual support. After the “baby churches” grow mature enough, they in turn keep sending or supporting church planters. This cycled pattern of “double-proliferation of church planters and churches”13 is known as the “dandelion model” of planting migrant churches, which embodies the value of “life does not end; the harvest is endless.”

5. Upgrade from monoculture to diversity

This refers to the diversity of the target groups of church planting. Since the 1980s, the composition of migrant worker churches has been rather homogeneous, with the majority of the congregation being middle-aged and made of migrant workers moving from villages to cities. Rarely could these people settle down in cities, and it was normal for them to keep moving around. In recent years, the migrant population has grown younger and has a higher educational background. In addition, the state has officially announced a policy to allow migrant workers to have their households registered in cities. Therefore, migrant workers can have their households registered in the cities where they work and settle down there. New churches in the future will reflect a mixture of people from cities and villages, permanent residents and migrant workers, middle-aged, seniors, younger generations, and so on.

Diversity is also manifested by the areas of church planting. The core areas of church planting are cities with concentrated populations. Based on these, new churches will be spreading into neighboring satellite cities and towns. In areas such as Beijing-Tianjin-Shanxi Province, Yangtze Delta and Pearl River Delta with highly concentrated populations, church planters are using cities as their bases and planting diversified churches in neighboring areas.

Conclusion

Today, urbanization is the important economic policy in China. The huge migrant population needs a stable work and living environment as well as spiritual health.

Migrant worker churches are duty-bound to spiritually nurture this group. On the one hand, they need to rely upon God’s guidance and protection to keep the churches alive and stable under special circumstances; on the other, they should grasp church planting opportunities brought about by migration to spread the gospel widely and win cities and the migrant population for Jesus Christ.

Bibliography

Books

Huang, Jianbo. Village Churches in Cities. Hong Kong, China: Tao Fong Shan Press, 2012.

Jin, Yingxiao. Study on New Types of House Churches in Beijing. Hong Kong, China: The Alliance Press, 2013.

Keller, Tim. Center Church: Doing Balanced, Gospel-centered Ministry in Your City. Chinese version, translated by Mingzhu He. Taipei, Taiwan: Campus Evangelical Fellowship Press, 2018.

Chinese Magazines

Gao, Shining. “Process of Urbanization and Christianity in China.” Religious Study, no. 2 (2011).

Yuan, Hao. “Migrant Worker’s Church in the Process of Contemporary China’s Urbanization: Case Study of ‘Mount of Olive Church’ in Beijing.” International Journal of Sino-Western Studies 9 (2015): 51-63.

Internet

“2020 Report on the Monitoring Survey of Migrant Workers.” National Bureau of Statistics of China. April 30, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202104/t20210430_1816933.html.

“住建部:我国常住人口城镇化率达63.89%” (“Ministry of Housing and Urban-rural Development: The Country’s Urbanization Rate of the Permanent Population Has Reached 63.89%”). Chinanews.com (中国新闻网). August 31, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.chinanews.com.cn/gn/2021/08-31/9554999.shtml.

Ren, Zeping. “Report on China’s Great Migration in 2021.” China Business Network. June 9, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.yicai.com/news/101077169.html.

Endnotes

- “住建部:我国常住人口城镇化率达63.89%” (“Ministry of Housing and Urban-rural Development: The Country’s Urbanization Rate of the Permanent Population Has Reached 63.89%,”) Chinanews.com (中国新闻网), August 31, 2021, https://www.chinanews.com.cn/gn/2021/08-31/9554999.shtml. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- As defined by National Bureau of Statistics of China, “migrant workers” are all people that still have a rural household registration but engage in non-agricultural work in their home area or leave their home area for work for more than six months per year.

- 2020年农民工监测调查报告(2020 Migrant Workers Monitoring Survey Report), National Bureau of Statistics, April 30, 2021. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202104/t20210430_1816933.html. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Ibid

- 2021中国人口大迁移报告 (2021 Population Migration Report) by 任泽平, Yicai.com, 2021-06-09https://www.yicai.com/news/101077169.html. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Ibid

- Yingxiao Jin, 2013, Study on New Types of House Churches in Beijing, The Alliance Press: Hong Kong, China, 37.

- Jianbo Huang, 2012, Village Churches in Cities, Tao Fong Shan Press: Hong Kong, China, 2.

- Shining Gao, 2011, “Process of Urbanization and Christianity in China,” Religious Studies, 117-118.

- Hao Yuan, 2016, “Migrant Worker Churches in Contemporary Chinese Urbanization,” International Journal of Sino-Western Studies, 54.

- Tim Keller, “Why Church Planting?” Acts 29, January 9, 2012, https://www.acts29.com/why-church-planting/

- The Dandelion Pattern of Church Planting conveys the image of dandelion seeds being easily spread by the wind with church planting following the same pattern—a geographic gospel saturation. The author’s thoughts about this concept have been taken largely from the Chinese versions of two books: Gary McIntosh’s, One Size Doesn’t Fit All: Bringing Out the Best in Any Size Church (translated by Hu Jiaen), (1999/2001), Taiwan, Taipei: Huashen, and Jim Belcher’s Deep Church: A Third Way Beyond Emerging and Traditional (translated by LiWangyuan), (2009/2014), Taiwan, Taipei: Campus.

- Craig Ott and Gene Wilson, 2011, Global Church Planting: Biblical Principles and Best Practices for Multiplication, Baker Academic.

Image Credit: A friend of ChinaSource

Mark Chu

Mark Chu (pseudonym), is a migrant pastor, completing his doctoral research on migrants in China. View Full Bio