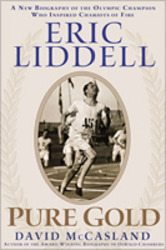

Eric Liddell: Pure Gold by David McCasland. Discovery House Publishers (Grand Rapids, MI: 2001), 333pp. ISBN 1-57293-130-2, $14.95.

Eric Liddell: Pure Gold by David McCasland. Discovery House Publishers (Grand Rapids, MI: 2001), 333pp. ISBN 1-57293-130-2, $14.95.

Reviewed by Wayne Martindale

Thanks to the academy award winning film “Chariots of Fire” (1981), many people around the world know that Eric Liddell won Olympic gold in a stunning world record finish in the 400 meters at the 1924 Paris games. His widow, Florence, whom he met and married in China, was pleased with the film and its portrayal of her husband.

Now, with all eyes on the Beijing Olympics, it is a good time revisit the film or, better yet, read an excellent biography of this man who was even better in life than in the movie, by all accounts. Of the scores of memoirs and biographies, the best is David McCasland’s Eric Liddell: Pure Gold (2001).

The meteoric rise to running fame is there, exciting and satisfyingly told. But the bulk of the story centers on China and the unfolding of character and commitment rare in the world—perhaps rarer than Olympic gold medalists and every bit as amazing.

The book is worth the time and purchase price just for the story of Eric’s parents. Their difficult, fearless and devoted missionary service was the template for Eric and his brother Rob in the next generation. At a time when China was in a state of “near anarchy” and power changed hands from one warlord to another, who in turn fought bands of marauders, Eric’s parents went as newlyweds to a pioneering mission station in Mongolia. In less than a year, the Boxer Rebellion (1900) rose against all foreigners and the Christian Chinese who had been influenced by them. The Liddells fled by cart with the help of Chinese Christians who risked their lives. Mary, seven months pregnant, was carried by sedan chair.

Over 200 Westerners died, many of them missionaries, and thousands of Chinese Christians fell to the sword while their homes and churches fell to the flame. Within months after the Boxer massacres, without knowledge of just what they would face, the Liddells returned to rebuild the burned-down station and mourn many Chinese friends who had been murdered.

Eric was born in 1902 in Tianjin. When Eric was ten months old, the Liddells piled their two boys into a houseboat for a week-long, 200-mile journey, then into two wooden-wheeled mule carts for another two days to the north China plain, an area infested with bandits. It was barren winter, but home to ten thousand villages and ten million souls who needed to hear of Jesus’ love.

Eric’s sister Jenny was born in1903. Ernest would be the fourth and last sibling, born in Peking in 1912. When Eric was five, the parents furloughed in Scotland and did what all missionary parents did (along with nearly all British parents who could afford it): they put their boys in a boarding school. As James returned to China, Mary and Jenny stayed another year to make sure all was well at the School for the Sons of Missionaries. When Mary went back to China, she knew it would be another six years before she would see her sons again.

After a few years at school, Rob and Eric began to take regular possession of first and second places in running and dominated the rugby field. At Edinburgh University, Eric quickly established himself as the fastest man in Scotland. Such was his fame that a young evangelist, having trouble drawing a crowd among both the working classes and students, had the bright idea of asking Eric to give his testimony.

We have all heard that the thing most people fear more than death is public speaking. Eric was so painfully shy that he would point to Rob to give an answer when asked a question during boarding school days. As he prayed about the request to give a public testimony, he knew God wanted him to do it, so Eric made one of the most important decisions he would ever make. In giving this testimony, he opened the door to finding God’s strength in his weakness, calling it, “The bravest thing I did in my life.” The crowds swelled at meetings indoors and out to hear the Flying Scotsman. For the rest of his college career, the weekly pattern was study, run, preach. He graduated near the top of his class in chemistry, won nearly every race he ever ran, and never said “no” to any invitation to speak when it was in his power to say “yes,” which was most of the time.

McCasland’s excellent book not only fills in the details of Eric’s pre and post Olympic life, it straightens out some misimpressions given by the movie for dramatic effect. First, Eric did not have to be admonished by his sister to go to China. It was in his heart from his youth. Second, Eric knew well before the Paris Olympics that Sunday scheduling ruled out the 100 meters, plus 4 x 100 and 4 x 400 meter relays. The decision was immediate and matter fact because his convictions were settled. Though heavily criticized in the press for jeopardizing Britain’s chances for gold, in the end, he was the only British athlete to win two medals in individual events. In the aftermath of victory, Eric was carried on shoulders, pulled in wagons, crowned with laurel at graduation and invited to meet the highest in society. In the midst of fame and adulation, at age 23, he left to follow his calling to China.

Eric’s mission was to teach at Tientsin Anglo-Chinese College (350 students) with the goal of reaching China’s future leaders. His responsibilities were math, science, athletics, dorm director and periodic chapel talks. He conducted well-attended weekly Bible studies and camps for poor boys. He was also Sunday School superintendent and studied Chinese two days per week. “Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might” (Ecc. 9:10) characterized this life devoted to others.

One of the many great stories in this book is Eric’s romance with Flo. When he proposed, she had just turned 18, and Eric was about to turn 28. She was surprised, but said an ecstatic “Yes.” After Florence’s three rigorous years of nurse’s training in Canada, they were married in China. Throughout their marriage, it was obvious to all that they were deeply in love, and Eric, a marvel with children of all ages, reveled in his two daughters.

Sometimes the biography reads like thriller spy novel. As China descended first into civil war, then Japanese occupation, the work became increasingly difficult and dangerous. On one of many dangerous journeys, Eric volunteers to go by boat to buy coal for the school and is robbed, then, sets out again with the money in a hollowed out French roll he carries (successfully) in plain sight.

Sometimes, in a single day as Eric traveled the country, he would be stopped and searched by armed men from the Japanese, the Communists, the Kuomintang Nationalists, local militias and bandits who would often be disguised as any of the above. He was regularly “questioned, detained, searched, and shot at.” A fellow science teacher at Tientsin Anglo-Chinese College had already been shot and killed by bandits. Even their journeys to the West were fraught with danger. On their furlough voyage across the Atlantic, ships near them were sunk by Japanese torpedoes.

Back in China, the Japanese took increasingly violent control. Eric sent Florence, pregnant with the third daughter he would not live to see, on to the safety of Canada, where Eric planned to join them in a few months. However, before Eric could act on this plan, the Japanese placed all foreigners in Tianjin under increasing restrictions until 1800 of them, from all walks of life, including Eric Liddell, were interred in Weihsien Camp. For the last two years of his life, Eric worked with the same energy, creativity and devotion that had always characterized his life. Tirelessly, he preached, wrote devotionals, taught chemistry (writing a text for the class) and organized athletic gameseven refereeing Sunday games for the nonreligious teens in the camp to keep them from fighting. He was so sought after by the young people that his camp roommates made a door sign letting people know if “Uncle Eric” was in or out.

Only a few months before the camp was liberated by American paratroopers, Eric Liddell died of a brain tumor. Such was the affection for him that the camp turned out for his funeral in unprecedented numbers. Such was his humility that many did not know until the funeral address that he was an Olympic hero. As his friend and fellow missionary, A. P. Cullen said at the funeral: “He was, literally, God-controlled, in his thought, judgments, actions, words, to an extent I have never seen surpassed, and rarely seen equaled.”

Readers of this remarkable book will find many special features, including: pictures, maps, a bibliography, index, epilogue on principle family members and places, and a listing of all of Eric’s races in Britain and the Olympics with his place (nearly always first) and the time. I wish it also had a chronology in list form; specifics are sometimes difficult to pick out of the context.

McCasland has also put together a 3-part Day of Discovery documentary of Eric Liddell’s life. It is worth watching (The Story of Eric Liddell from Discovery House Publishers). Another biography worth knowing about is Eric Liddell: Something Greater Than Gold by Janet and Geoff Benge. This one is half the length and reads quickly and engagingly and would be a good pick for younger readers or anyone who wants less than a full-length biography. However, McCasland’s book is easy to read and worth the extra timebut with this caution: it will almost certainly be convicting.

Wayne Martindale

Dr. Wayne Martindale, professor of English at Wheaton College, has taught in China with his wife, Nita, five times since 1989. He is co-editor of The Quotable Lewis and author of Beyond the Shadowlands: C. S. Lewis on Heaven and Hell.View Full Bio