Students at the school for the blind with Emma Ekvall in the back row on the left.

A blind girl begging at the gate of the Christian & Missionary Alliance (C&MA) mission compound in Wuchang, China in 1919 stirred the heart of Mrs. Emma Ekvall, née Ek. The school she then founded as a personal work of faith—beginning with four abandoned blind waifs—continues in operation today upon the anniversary of this pioneer missionary’s 150th birth. In fact, a statue commemorating her vision was erected in front of the school’s impressive new campus by the People’s Republic of China two years ago.

Born in Morlunda, Sweden on August 19, 1870, Emma at 18 years old was converted during a revival sweeping the province of Smoland. She’d heard of Hudson Taylor’s work so, resisting her State pastor’s urging to serve in Africa, as well as friends’ advice to remain home and teach school, she sailed alone for London to apply to the China Inland Mission. She was assigned for training to a seaman’s mission and later to village evangelism. Years later Emma testified she’d asked for 12 souls’ salvation as a token of assurance and was wonderfully answered with over 70 in a year.

Emma again revealed her grit in 1891 when, upon landing in Shanghai, her country’s consul rudely scolded her that China was no place for a single maiden, adding disdainfully, especially to preach the gospel. She ignored his order to go home.

After a year of language study Emma was appointed to Baoning Fu (Langzhong) in Sichuan where she opened a number of out-stations serving under Bishop William Wharton Cassels of the “Cambridge Seven.” Further demonstrating her initiative, by “doing a small amount of medical work” on the wives of higher class officials, Emma earned the rarity of invitations into homes of the privileged, to weddings, feasts, and burials. Upon leaving on furlough in 1898, she had witnessed conversions and ushered five ladies into a Bible class then led by Mrs. Cassels (expanding in time to over 20).

During this first term she accepted the proposal of a persistent naturalized-American Swede, (Eric) Martin Ekvall who had grown up in Krisdala, just 12 miles from the Ek family’s town. His family had immigrated to America where he and siblings David and Otilia were inspired by Rev. A.B. Simpson to seek the lost of Tibet. Upon graduating from the C&MA Institute in New York City, all three eventually served in Gansu. Emma and Martin married during furlough in New Hampshire in 1900 and returned under the Alliance to postings in Anhui and Hunan, during which Gertrude, the first of their five children, was born.

The Ekvall family journeyed in 1904 to Minchow in far west Gansu where Martin and his brother David had first opened a station ten years earlier. The married couple worked tirelessly to grow the young church. Emma set up a school for girls, both educating them and sharing the gospel.

Emma’s letters home revealed difficulties, including threats on life by the xenophobic Old Brother Society. Bandits were a constant menace as Minchow was besieged and looted. The spread of war at the end of the Manchu Dynasty isolated Gansu from most of the outside world, especially access to medical care. Three of the now five children contracted scarlet fever in 1911, 6-year old Elizabeth dying. Emma was both physically and emotionally drained when the family returned to the U.S. for an overdue furlough. Fully restored when the seven Ekvalls returned to China in 1915, Emma would now cement her 48-year China legacy.

In the midst of assisting Martin in pastoring the same Wuchang church in the C&MA’s Central China field he’d first pioneered upon Simpson’s instruction in 1893, Emma weathered the loss of a second child, Irene, to the Spanish Flu. (Their only son, Henry, would be robbed and murdered outside Xi’an in 1932.) The Lord providentially provided her a new focus: the will and tools to restore impaired and unwanted women into productive society. It wasn’t easy. From first housing in another society’s building, a $5 gift from America encouraged her to rent space near the church and, finally, to buy a commodious two-story building for the eventual 50 live-ins.

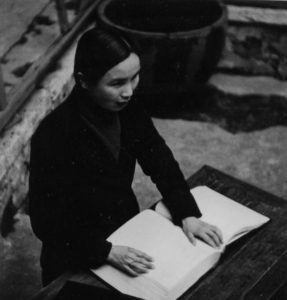

With a capable matron as supervisor, Emma recruited instructors in Chinese Braille, at first for lower grades then high school. The Bible was their major study and hymn singing a favorite pastime. Some women memorized whole books of Scripture and the hymnal.

The girls’ choir sang in the Alliance services with one of their own actually at the organ. On Sunday mornings walking down the narrow, crowded street, the long line of blind created a minor sensation in the neighborhood. Single file and graded for height from smallest to tallest, each with a hand on the shoulder of the girl ahead, they followed a teacher. The girls became remarkably proficient: being taught sewing and other hand crafts, carrying out assigned daily chores.

Besides overall administration, Mrs. Ekvall organized a Blind School Committee of local missionaries from several denominations. But her singular responsibility was raising independent funds. She drew upon wide contacts in the States with Swedish Baptist churches and individuals, such as Robert Dollar of the steamship line and Mr. Lee Jui, wealthy wood merchant. “I trust the Lord to provide,” she often said.

About ten years into the work Emma opened a separate school for deaf mute boys and girls whose parents paid modest tuition. By the time the Alliance was forced to leave the country around 1949 some 48 of these graduates were earning their living.

Situated on the Yangtze River, Emma spearheaded relief work in the refugee camps during the epic 1931 and ’32 floods. She was cited by the mayor of Hankou and awarded a medal in behalf of Madame Chiang Kai Shek.

It should be added that after Martin died in January 1939 and Emma was evacuated during the Sino-Japanese War, the school for the blind was overseen first by Alliance deaconess Gertrude Stewart and, after Pearl Harbor and during Japanese occupation, by Miss Florence Liu, a graduate of the Perkins Institution. Emma was on one of the first ships to return in early 1946 and carried on until again ordered out in 1948 during the Civil War. In continuing to speak wherever invited, her interest in her beloved China never waned until God called her home at 82.

All images courtesy of the author.

Ray Smith

A grandson of Emma Ekvall, Ray Smith was born in Guling on Lushan in 1932. The career journalist represented the US Telephone Industry at the opening of the American Embassy in Beijing in 1979. He led delegations of US professionals holding telecom workshops in the PRC in 1982, 84, and …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.