The plight of China’s Uyghurs has caught the world’s attention, but what about the Hui and China’s other eight Muslim minorities? In this new series, I share the most eye-opening and actionable things I learned from the Know Thy Hui Neighbor (KTHN) training. This course trains local and overseas Christians to share Christ’s love with the Hui. The training’s rationale and structure can be found in part 1 of the companion series, From the Middle East to the Middle Kingdom.

Numbering 10.5 million, the Hui are the largest Muslim minority group in China, just ahead of Uyghurs at 10 million. Hui are scattered throughout China and speak Mandarin. For many Han Chinese Christians, the Hui are their nearest cross-cultural neighbors. Yet they are often overlooked. Hui are similar enough to the Han that they don’t grab the attention of Christians looking to serve “cross-culturally,” but, at the same time, they are different enough to make Christians uncomfortable or even afraid to share the good news with them.

Know Thy Hui Neighbor exists to decrease barriers and increase understanding that leads to fruitful relationships with Hui people. This series will introduce you to some of the different schools of religious thought and practice, Hui diet, dress, customs, and festivals. I will also share stories of how the gospel has been shared and received and provide some pointers for Christians seeking to better know and love their Hui neighbors in the name of Jesus.

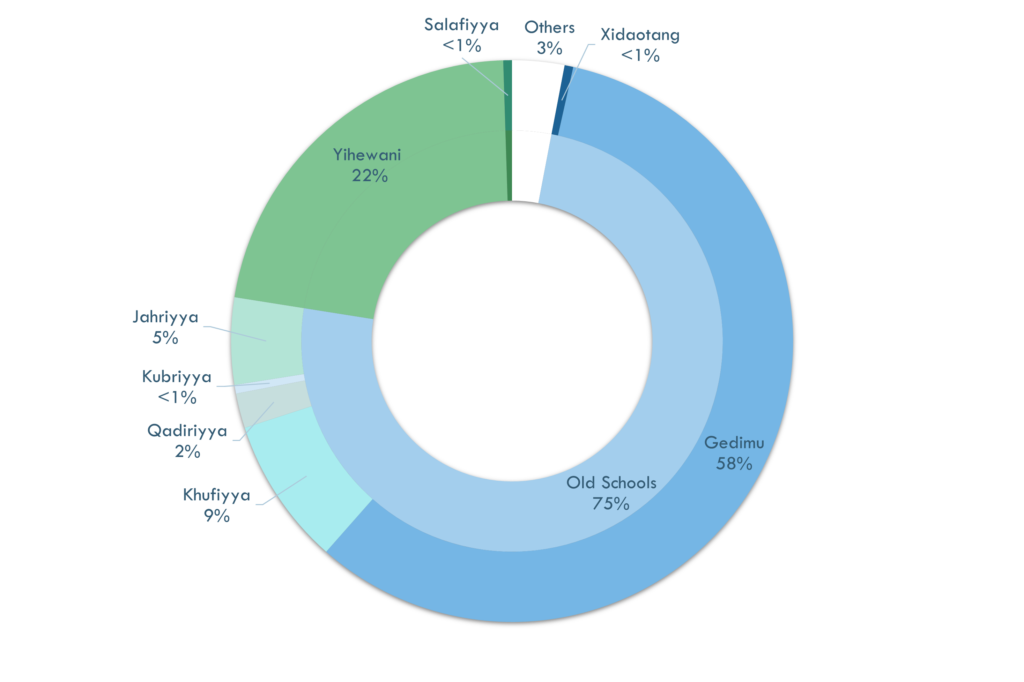

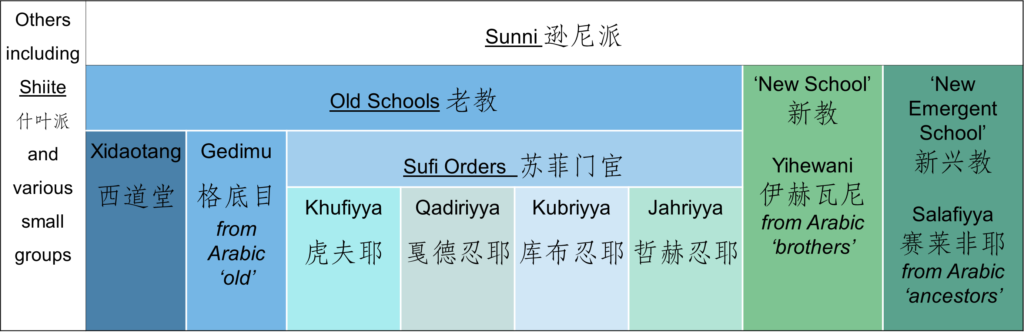

The Islam of the Hui is diverse and divided into what I will call “schools of thought and practice” or simply, “schools.” The Chinese names of the eight main groupings are listed in the table above, along with the English translations I will use in this series.

Hui Muslims are almost exclusively Sunni.1 The largest division is between the Old and New Schools, as viewed from a Chinese perspective. Older schools arrived in China earlier and have integrated more Chinese cultural forms (see below and part 2 in this series). The New and Emergent Schools (part 3) appeared much later. Both of these began as reform movements aimed at the de-Sinification of Islam in China.

The Old School

The largest school by population is the Gedimu, boasting 58% of Hui.2 Gedimu means “old” (from Arabic Qadim). Their traditional mosques are built in such typically Chinese style that they are easily mistaken for Daoist or Buddhist temples. Yet, we cannot be sure a mosque is Gedimu by its architecture alone. Some were torn down during the Cultural Revolution and later rebuilt in Arabic style. Some Old School buildings have come under New School leadership. Many have now had all external religious elements removed under Xi Jinping’s Sinification campaign.

When I arrived in a Hui village on the outskirts of an East Coast city, the halal restaurants, green archways, and the absence of red door hangings typical of Chinese homes told me I was in the right place. “But where are all the Hui people?” I asked my host.

“You’re looking at them,” came the reply.

I was at that moment looking at a group of young women in short skirts and heels, their thick makeup melting in the summer heat. Nearby, middle-aged men were playing cards and smoking cigarettes, cooling off by rolling up their t-shirts to expose their midsections.

These Hui are Gedimu. I was soon introduced to Shelly3 and her friends. I quickly learned that they did not know which school of Islam they belonged to, but it was “not that new group who meets in that apartment over there.” (We’ll learn more about them in part 3 of this series.) To these Old School Hui, Islam meant belonging to their local community, only marrying local Hui, and avoiding pork. They knew they should pray five times a day, cover their heads, and give alms, but those duties were more critical towards the end of life.

Gedimu neighborhoods center around a local mosque. The mosque serves as a community service center: the place Shelly’s mother gets her chickens slaughtered, where her grandfather’s body was prepared for burial, and where her father catches up on gossip most days but only joins prayers once on Fridays. Gedimu mosques are independent and not well networked. When away from home, even a devout Gedimu Hui is unlikely to visit another mosque. In another Chinese city, I asked members of a Gedimu family what they would do while their neighborhood mosque was closed for renovation. “No problem,” they said. “If we have a wedding or a baby, the ahong will visit our home to recite the scriptures.”

Apart from the ahong (Muslim cleric or imam), not many Gedimu read their scriptures. Elders pass down “Quranic stories,” but most of these come from hadith (Islamic traditions) or Chinese sources rather than the Quran itself. Overall, doctrine is a low priority.

Gedimu Hui tend to be shy towards outsiders and more interested in their local community than global issues or global Islam. Brother Liu,4 a Chinese cross-cultural worker, tells a story of how he got chatting with a Hui man outside a restaurant. As the time for prayers approached, nearby men started heading towards the mosque, and Brother Liu asked if his new friend was going too. “What does it have to do with you?” exclaimed the man defensively, “If I go or don’t go, it’s my business!” Liu apologized for intruding and slowly built the friendship over several months. After Liu brought gifts of fruit and boxes of milk, his new friend opened up to him. “Hui of the Old School might be hard on the outside,” says Brother Liu, “But be encouraged. On the inside, they are very soft. When they realize you truly care about them, they will share their hopes, their doubts, and even their failings with you. Once they trust you, they really trust you. So, you have to be trustworthy.”

The Old School is aptly named. A traditional, cultural Islam, whose stories are told but forgotten, introverted, unconnected, non-threatening, even a bit boring, and gradually fading away in modern secular China. All this makes a relatively effective shield against state-sponsored religious persecution. The same shield deflects outsiders and their foreign ideas, as Brother Liu found out, but with enough time, friendship can grow, and perhaps their soft hearts will open to the love of God.

pmorgan from ?, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia CommonsEndnotes

- Shiites in China are extremely few and most are expatriates.

- All percentages are approximations based on: 马通. (2000). 中国伊斯兰教派与门宦制度史略(修订本). 宁夏人民出版社. and Gladney, D. C. (1999). “The Salafiyya Movement in Northwest China: Islamic Fundamentalism among the Muslim Chinese?” In L. Manger (Ed.), Muslim Diversity: Local Islam in Global Contexts. Curzon Press. Both sources rely on data estimates circa. 1979. The number of Gedimu Muslims is said to be shrinking, but I have no specific data. I invite readers to contribute updated statistics and further research.

- Not her real name.

- Not his real name.

Image credit: pmorgan from ?, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Julie Ma

Julie Ma (pseudonym) is a graduate of Sydney Missionary and Bible College (SMBC) and a member of the Angelina Noble Centre for women in cross-cultural missions research. She left her home in Australia over a decade ago to serve Hui Chinese Muslims alongside her Chinese husband. After all these years overseas, …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.