The bleak picture of Hui life during the Cultural Revolution (see part 7) brightened up when Deng Xiaoping took the lead. He opened China to trade and travel. His economic reforms gave the right to do business back to the people. Hui people jumped at the chance to reopen their old family restaurants and shops, and an influx of local and foreign tourists brought new markets for their wares. As their wealth grew, Hui businesspeople could afford to take advantage of their newfound freedom to travel outside China. And where would you go if you were a Muslim with a once-in-a-lifetime chance to go abroad? Mecca of course! A hajj, or pilgrimage to the Muslim holy land, is one of the five pillars of Islam.

With globalization came a flood of ideas, people, and money from the Islamic heartlands. Hui pilgrims studied Islam in Arabia and brought home all they learned. They networked throughout the Muslim world and brought back teachers, books, and sponsorships. Mosques destroyed in the Cultural Revolution were rebuilt in grander, more modern, and often more Arabic style. The Hui were reawakened to Islam. Muslim missionaries, some foreign and some from China, helped the spread of the New Teaching (Yihewani, see part 6) and a small but growing Salafi movement (dubbed 新兴教, xinxingjiao, Emergent Teaching).1 One notable Muslim missionary is a Hui man who calls himself Mr. Fig (无花果, Wuhuaguo). Through his books, itinerant preaching, and the Green China (绿色中华, lüsezhonghua) website, he calls all Muslims to unite under one banner. He addresses Han Chinese as well, reminding them that the Chinese ancients worshiped the one true God, who is in heaven. Islam, he says, is the pure and true expression of traditional Chinese monotheism.

Just as Muslim missionaries found themselves having new freedom, enthusiasm, and resources to spread Islam, similar doors were open to Chinese and foreign Christians. They came from everywhere, not only English-speaking countries. They came, not with public identities as missionaries, but as teachers, students, workers, and tourists. They were creative and diverse in their approaches to sharing Christ’s message and their relationships with the Hui people they met were not always straightforward.

Habibi is a Hui Muslim described as having “a penchant for befriending foreigners in Xining, including many missionaries.”2 He says that, earlier in his life, certain foreigners tricked him into being baptized,3 but this didn’t put him off continuing to make Christian friends. He seems to have embraced multiple identities. His American anthropologist friend, Alexander Stewart, certainly pegged him as a devout Muslim. Yet, Habibi also became well-known among Xining’s foreign Christian community as a Muslim “seeker,” at times being falsely identified as a Muslim Background Believer (MBB). Many were shocked when Habibi posted some of the sensitive information he had gathered about foreign Christians online. Was he a spy? Or was he just trying to protect his fellow Muslims from being tricked in the way he believed he had been all those years earlier?

What happened with Habibi is used as a case study in the KTHN training, but it was not an isolated event. There are others like him and there always will be. Relationships with MBBs, or anyone for that matter, need to be navigated with godly wisdom.

If someone is very keen to talk spirituality with you, pause and take stock. Are they like the Bereans (Acts 17:1) genuinely seeking truth, or are they a Mr. Fig trying to convert you to Islam? Are they a Habibi who might put you and your co-workers at risk? None of these scenarios means you need to cut the person off, but in all circumstances, be innocent yet wise (Matthew 10:16).

“Missionaries” of other kinds came into the newly reopened China, too. A flood of people from all over the world introduced the Hui to the “religions” of wealth, status, and secularism.

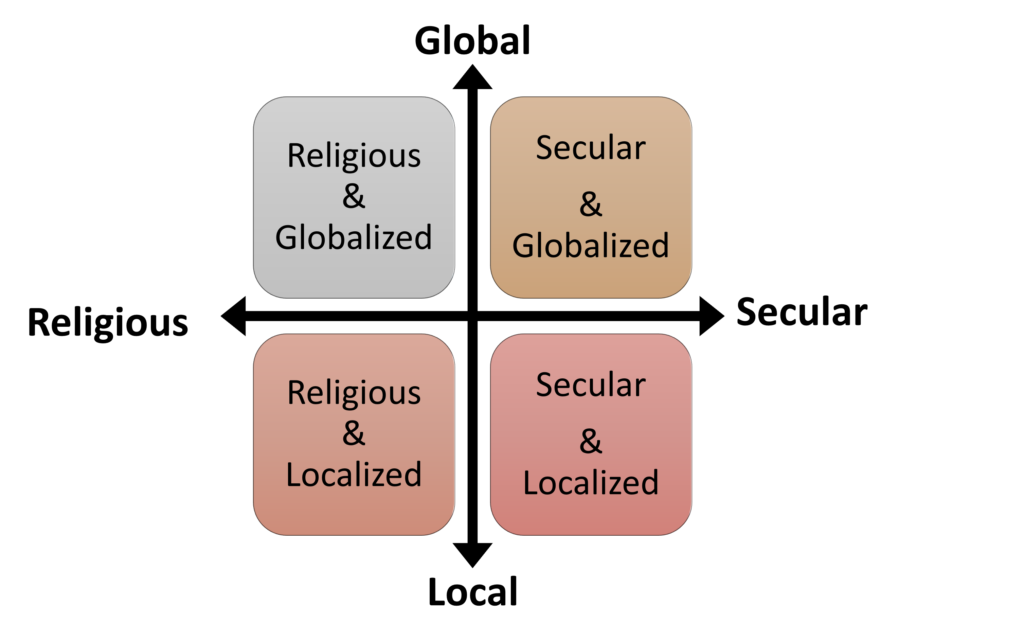

With all these choices, the Hui naturally responded to China’s opening up in different ways. Some became secularized, others used their freedom to become more religious. Some embraced globalization while others kept their hearts and minds close to home. When we engage in conversation with a Hui person today, it can be helpful to ask ourselves how they identify on the spectrum between religious and secular, and between local and global (see figure below).

We can think about a person’s identity as a blend of qualities, not simply label them as “Hui” and expect them to conform to our expectations of what that means. The four quadrants can help us navigate which topics might interest our Hui friend, what questions to ask them, and how we might present the gospel in such a way that they agree it really is Good News.

So far, our series has covered the broad strokes of Hui history from the Tang Dynasty to the present day. In the next post, we will meet some early Christian missionaries to the Hui. Whether we are leaders or followers, innovators or lovers of tradition, we have much to learn from those who have gone before us.

Endnotes

Image credit: 回坊风情街 by cotaro70s via Flickr.

Julie Ma

Julie Ma (pseudonym) is a graduate of Sydney Missionary and Bible College (SMBC) and a member of the Angelina Noble Centre for women in cross-cultural missions research. She left her home in Australia over a decade ago to serve Hui Chinese Muslims alongside her Chinese husband. After all these years overseas, …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.