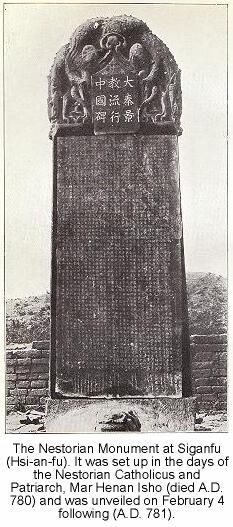

Many readers will have heard of the so-called “Nestorian Stele,” more appropriately called the Xi’an stele, shown in the photos above and below. More recent scholarship of the stele and the church attached to it follows the convention of not designating the group “Nestorian,” as this implies the only important thing to know about the group is their association with the figure Nestorius, who was deemed heretical by the Byzantine church in the fifth century.[1] This stone pillar, containing roughly 2,500 Chinese characters, was set in place in 781. It narrates the history of Assyrian Apostolic Church of the East and its relations with the Tang Dynasty court and empire starting in 635, and ending in 781.

Having published a book on the topic recently, and having spent much of the last ten years studying how the text of the stele relates to other Chinese sources from the period, as well as Syriac and Arabic materials from the stele’s west and from the same time, I was delighted when the editors at ChinaSource agreed to allow me to share a few thoughts on the stele and what it has to tell us today with regards to Christianity and the government’s Sinicization policies.

In the interest of full disclosure, I need to make two things clear at the outset. First, I am not an expert on the regime of Xi Jinping. I have been to China recently, and have paid attention to the recent changes, but this is knowledge gained at something of a distance. Secondly, although raised with Western Christianity (both Protestant and Catholic) originally, for the last decade I have worshipped God with the ancient Christian communities of the Middle East and Eastern Europe (both Eastern and Oriental Orthodox). I tend to see through the eyes of their culture and traditions (to the extent that a Westerner can), which are quite different from Protestantism—though I firmly believe all Christians share an ontological linkage in Christ.

My comments about the Xi’an stele are going to reflect all of these influences, and will hopefully be of value because of this. They also may offend because of this, and for this, should it happen, I beg pardon in advance.

A Political Lesson from the Xi’an Stele

Christianity was officially welcomed into China in 635, and was officially asked to leave in 845. Without this official recognition, the church in the Tang would not have existed at all. The sources also indicate that a form of détente was worked out between the church and the Chinese state—one was not to interfere with the other in doing what it did best.

This was quite distasteful to Japanese researcher P. Y. Saeki, an early pioneer in stele research, a Protestant, who put forth, in several of his writings, the idea that it was this closeness to power in the Tang empire that caused its demise (see The Nestorian Documents and Relics in China by P. Y. Saeki). We do not really know the extent to which the church in the Tang believed it when it showed loyalty to the Tang court (and fought for it during the An Lushan Rebellion of 755-63). What we do know is that this was not why the church disappeared in early medieval China. When the Uighur Empire began to crumble in Central Asia in the early 840s, the Syriac Christians, who were well placed in both the Uighur Empire and the Abbasid Islamic Caliphate as translators and cultural interlocutors, were no longer deemed useful to the Chinese government within the new political climate. What this means for Christians in China today, is that they may do well simply to let government do what it thinks best at this moment. The Assyrian Church of the East, the church responsible for the Xi’an stele and the main Christian church in Iran, Central Asia, and China through the Middle Ages, simply “rolled with the punches,” and went back to Central Asia and other homelands in 845 when they were asked to leave.[2] They returned to China when the political situation improved.

During the Mongol Empire (13th and 14th centuries), Mongol princesses and key figures within the Mongol court were Assyrian Christians. Christianity in medieval China was made official because it was useful, because it was integrated, and because it played a role both in international relations and interregional relations. Eastern Christianity is alive and well on China’s borders with Russia and Central Asia. As China’s economic relations with these regions deepens, and its new version of the Silk Road, its One Belt, One Road initiative, moves forward, this is a context in which leverage for the worldwide church can be gained, and China can be made to see that Christianity is part of the world’s heritage, and not merely a by-product of Western imperialism starting in the early modern period.

A Spiritual Lesson from the Xi’an Stele

Also highly distasteful to P. Y. Saeki was what in the Xi’an stele appears, at least on the surface, to look like a divine emperor ideology, similar to that seen not only in medieval Buddhist and Daoist materials, but seen in Iranian and Central Asian materials as well. Here is the place where, if I am not careful, I am going to lose my Western Christian co-religionists. Eastern Christians understand today and understood in the past God’s holiness as having an ability to transmit through and into the world of matter. This is often different from a Christianity derived from Enlightenment-era thinking, in which matter and spirit are opposed to one another (and which Pentecostalism arose as an antidote). Medieval peoples— Jews living in Christian Europe, and medieval Christians living in the Muslim world, for example—tended to have less trouble than moderns when following religions that differed from their own.

Medievals shared a world-view (at once spiritual and political) with their sovereigns and their courts, one based in a mystical, imperial theology. Eastern Christians are often accused of Caesaropapism, and it is often not noticed that Christians found ways to navigate this tension and still remain faithful to the gospel. Many key eastern saints were seen as saints because they opposed their emperors on matters of faith. The Christians of the Tang period in China even translated Buddhists texts for the emperor on one occasion, and did this because the spiritual power of the church and its leadership was thought to benefit the empire and the person of the emperor and not be tainted by involvement with Buddhist texts.[3]

Nathan Hatch’s book The Democratization of American Christianity, focused as it is on late eighteenth century America, has a cover which is quite powerful.[4] It uses an 18th century American painting showing a congregation, following a sermon, sprawled out upon the church floor as if all were asleep in a massive slumber party. The book argues persuasively for a “flattening” occurring within American Christianity at the time of the American Revolution. This was part of, and even instrumental within, the cultural rejection of Anglicanism and its high church theology that occurred during the American Revolution, and had ramifications far beyond the political realm, and shapes American Protestant thought to this day.

Though we cannot change the past, and the American church and the polity it grew alongside would not have been what it was without this flattening and rejection of sacramentalism and ritual, this can also divorce us from the historical lessons and future potential of Eastern Christianity in China. The Christianity that not only survived, but thrived, in early Medieval China was at once biblical, charismatic, and spirited-filled Christianity, but it was also sacramental, eucharistic, and liturgical. It flourished, and still flourishes, in the Syriac church around the world, not only in spite of any opposition to the state, but because of this opposition. It is not the case that liturgical and sacramental Christianity is weak in the face of the state.

C.S. Lewis said that for a religion to be great, it must be “thick” and “clear.” “Thick” here means that it was culturally embodied and based in heart-felt ritual (see his novel Til We Have Faces, where this phrase also appears towards the end of the book). “Clear” here means that it was ethically profound, global in its reach, and un-muddled in its doctrine.[5] Christianity in the Tang Empire was definitely both thick and clear, and thus has a spiritual lesson for how to think about the church in China in the current context.

Header image credit: Nestorian Stone, 781 AD by Gary Todd via Flickr.

Text image of stele: Stele text by Nestorian monk Jingjing. Photo either made by Henri Havret, or a local collaborator of his, or reproduced from an earlier Chinese source. There is a caption in Havret's 1895 publication, possibly explaining the provenance, but it's hardly legible. – The photo was originally published by Henri Havret (1848-1901), in his La stele chrétienne de Si-ngan fou (part 1), Variétés sinologiques No. 7, Paris, 1895, near the front cover. This scan is as reproduced as Plate III in SIR E. A. WALLIS BUDGE, KT., THE MONKS OF KUBLAl KHAN EMPEROR OF CHINA (1928), Public Domain, Link

Todd Godwin

R. Todd Godwin received his PhD from the School of African and Oriental Studies (SOAS), University of London, and lectures at the Institute for Orthodox Christian Studies, Cambridge, UK and the Classical Language Learning Resource Center in Idaho. He has published in peer-reviewed journals on the early medieval church of the …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.