This is part nine of the series “Know Thy Hui Neighbor” based on the Know Thy Hui Neighbor (KTHN) training. This course is to train local and overseas Christians to share Christ’s love with the Hui.

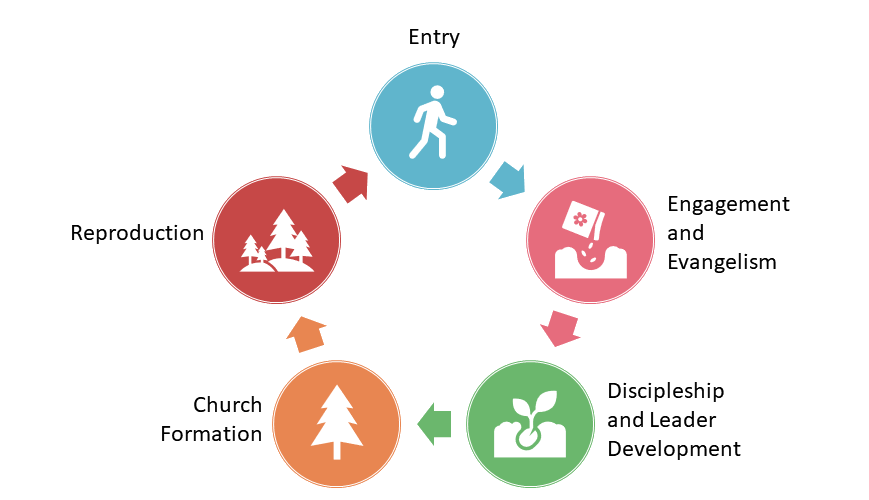

“Know Thy Hui Neighbor” arranges its ministry advice around a church planting life cycle.1 The course describes five stages which are somewhat fluid and overlapping: entry, engagement (including evangelism), discipleship (including leadership development), church formation, and reproduction.

In this series, my goal is to help beginners take their first few steps in sharing God’s love with the Hui, so I will only walk through stages 1 (entry) and 2 (engagement). From the many “dos and don’ts” listed in the course, I have selected just a few which correlate to lessons in these two blog series. I already covered some basics of stage 3 (discipleship and leadership development) in my previous article, “Hui Disciples of Jesus,” but space precludes diving into stages 4 and 5 here.

Yet even for beginners, it helps to keep the whole CP life cycle in view. There’s no need to overwhelm yourself with all the details early on, but we can better discern our next step if we have some idea where we are heading. It’s hard to change the DNA of an established church; much easier to build healthy life from the beginning. So, from the moment we enter a community, we should already be asking ourselves questions like these:

“What sort of worshipping community might be appropriate for these people?”

“When these people become followers of Jesus, who will they fellowship with?”

“How can these new believers share Christ wisely in their community?”

“How does my conduct and leadership make it easier or harder for these potential future leaders to ‘imitate me as I imitate Christ’?”

Stage 1: Entry

Two Case Studies: What Not to Do

Brother Yang2 is a Han believer sent to work with the Hui in northwest China. Upon arrival, he went to a prominent mosque and introduced himself as a student of Islam. The ahong (imam, Muslim cleric) fed him, discipled him, and took him to Islamic conferences and events. Yang’s understanding of Islam and Hui community skyrocketed. But how could he share his faith in Jesus? Soon Yang’s wife started having nightmares. Then one day, another ahong pointed his finger at him, saying, “You are a Christian missionary, sent to convert us!” He found a way out that day but was too scared to go back.

Jenny3 is an unmarried businesswoman from an overseas Chinese community. She visits Hui neighborhoods wearing a silver cross necklace and always has a Bible in her bag. She enjoys intellectual conversations and especially thrives in religious debates. She finds the Hui men easier to talk with than the women. She has been called by the local police department to “drink tea” a few times, but the officers are always friendly and agree she has not broken any laws.

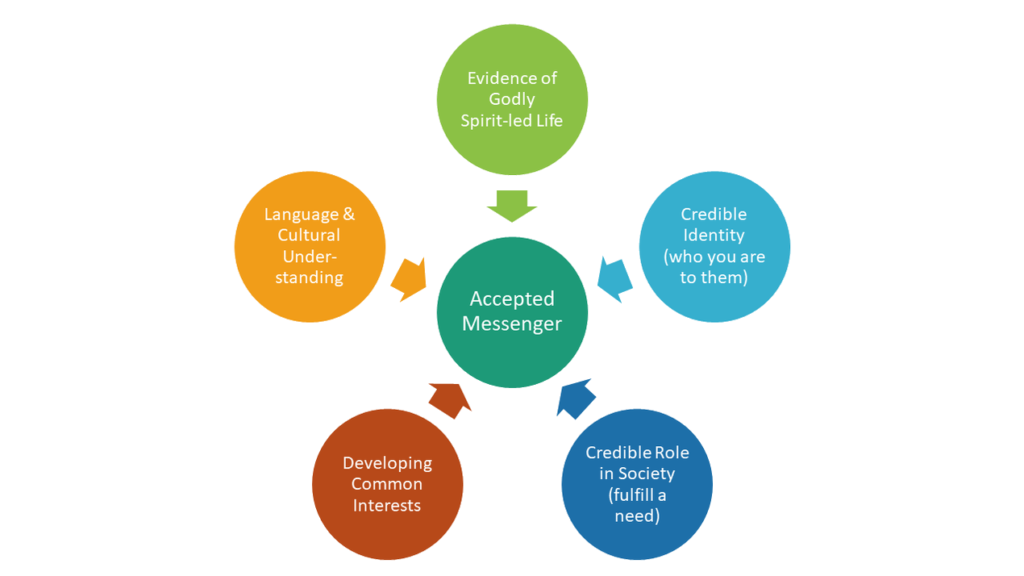

Neither Yang nor Jenny did entry well. Despite having some knowledge of Hui culture, they both failed to conduct themselves as good messengers of Christ in that culture. As well as knowing the gospel, you need to know where you are—the Hui context—and who you are. Roland Muller’s book The Messenger, the Message, and the Community fleshes out the interplay between them.4 The diagram below could help each of us think through our identity as a gospel messenger in their context.

Applying History and Culture Lessons

In the preceding eighteen articles, we’ve gained some fascinating insights into Hui history and culture. Yet this knowledge will not help us until we apply it to our personal decisions about how to conduct ourselves among our Hui friends. My experience tells me cross-cultural workers have less difficulty applying lessons about religious beliefs, food, clothes, celebrations, and rituals, so I will use the limited space I have here to draw out some principles from a sometimes overlooked part of Hui culture that the Hui themselves are passionate about—their history.

Because we learned how Hui identity is built upon their ethnogenesis, we know we can connect with them through our shared experiences of limited religious freedom, through small business interests and food, and through being immigrants or minorities (if these are true of us). We learn not to minimize the importance of Islam to Hui identity or hastily criticize their religion. Meanwhile, we should expect them to enquire about our stories. Be ready to explain your presence here among the Hui in a way that makes sense to them.

Knowing how the Mongol rulers treated the Hui helps us understand their wide geographical spread and their peculiar mix of religious pride and social shame. It teaches us not to be one-dimensional, neither to pity them nor give undue admiration.

In the Ming dynasty, we find the origins of the “us versus them” mentality that divides the world into Hui and Han (by which they really mean “non-Hui”). We learn why Hui speak differently from other Chinese, even when they speak Mandarin, why they prefer to marry other Hui, and how they came to reframe their distinctive Islamic practices in terms of filial piety and Chinese wisdom. We learn not to assume they are devout Muslims but nevertheless expect them to talk at length about halal food, abhor pork, and probably avoid alcohol.

The Tongzhi Uprisings teach us how easily an “us versus them” attitude can bring disaster. But learning not to reinforce divisions is easier said than done—especially if we belong to a group with ethnocentric tendencies or longstanding animosity toward the Hui.

Stage 2: Engagement and Evangelism

We started our first series with the case of a well-known evangelism tool not connecting with Hui people. Hui have been steeped in religion all their lives. They’ve heard eloquent sermons from impeccably dressed teachers who pray five times a day but go home to a terrible marriage, addictions, and worse. They need to see you are different—imperfect but upright, having an honest moral integrity empowered by the Spirit of God.

Hui have small circles of trust—and for good reason. Forced conversion, betrayals, surveillance, and controlling leaders continually stoke fear of dangerous “others.” They need to see you are trustworthy. Meet them in small groups or one-on-one. Don’t push them to meet strangers—even Christian strangers—before they are ready. Focus on the process rather than some kind of measurable outcome.

One More Case Study: Connecting through Conversation

Doreen5 works in a tech company, but her real passion is counseling. After she helped a junior colleague recover from a difficult break-up, word spread at the office that she was a good listener. Her friends and neighbors feel safe in her home. They come for advice on everything from wayward children to domestic violence. Doreen tells them she’s not a psychiatrist. Her wisdom comes from the Holy Scriptures and the Spirit of God dwelling within. Some people scoff at the idea God cares about them. Others agree to receive prayer. A handful have made Doreen’s Lord their Lord too.

How does Doreen’s approach differ from the case studies of Yang and Jenny? Her strategy is her life lived out. She shares the gospel not through sermons, but through conversations prompted with wise questions.

Where do you live? What do you eat? Who did you marry? Why?

What’s your favorite story? Who are your heroes?

If your friend is unsure which school of Islam they belong to, ask which festivals they observe and whether they know who founded their order. Ask whether they chant, use incense, and visit tombs,

Whichever way your conversation goes, let it lead to a question like this:

Has anyone told you what the prophet Ěrsā Màixīhā (尔撒麦西哈; Arabic: Isa al-Masih; English: Jesus the Messiah) says about this?

Then tell one of Jesus’ parables6 or read a few of his words and ask your friend what they think it means.

Maybe you don’t yet know what God’s Word says about such everyday issues. In that case, open your Bible and find out. Let your Hui friend listen as you seek the Lord you love for answers. Let them watch as your eyes are opened to the riches of his revelation. Perhaps also join you on your journey of discovery, praying with the Psalmist:

Open my eyes to see wonderful things in your Word.

I am but a pilgrim here on earth: how I need a map

and your commands are my chart and guide.

Psalm 119:18–19 (TLB)

Endnotes

- Adapted from models described in: Craig Ott and Gene Wilson, Global Church Planting: Biblical Principles and Best Practices for Multiplication. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2011), chapter 8.

- Not his real name.

- Composite character.

- Roland Muller The Messenger, the Message, the Community: Three Critical Issues for the Cross-Cultural Church Planter, 3rd edition. (Canada: CanBooks, 2013), chapter 1.

- Name and some details changed.

- Parables we have seen resonate with Hui include the four soils (Matthew 13:1–23; Mark 4:1–20; Luke 8:1–15), the clean cup and dish (Matthew 23:25; Luke 11:39), and the two lost sons (Luke 15:11–32). More on using parables in: Muller (2013) pp. 56–59.

Image credit: Julie Ma. Image for illustrative purposes only.

Julie Ma

Julie Ma (pseudonym) is a graduate of Sydney Missionary and Bible College (SMBC) and a member of the Angelina Noble Centre for women in cross-cultural missions research. She left her home in Australia over a decade ago to serve Hui Chinese Muslims alongside her Chinese husband. After all these years overseas, …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.