Conflicting Social Identities

Teachers of the Liberal Studies course in Hong Kong’s secondary schools faced a new challenge this year. For the first time, they needed to prepare to teach a revised core subject without the benefit of approved textbooks.1 The contents had come under increased scrutiny and criticism as some thought the course was a means of encouraging anti-China sentiments among the students. One factor being cited was a lack of neutrality in discussing Chinese citizenship and thus impacting how students identified themselves as citizens of China or of Hong Kong.2 The revised course, now renamed “Citizenship and Social Development”, was put into place but without enough time for the textbook publishers to respond with new textbooks in time for the beginning of the new school year.

This issue of multiple ethnic identities not only affects teachers and students, it has also aroused controversy in society generally and in the church. Unity is disrupted in social circles and fellowships. In addition, increased focus on local identity contributes to declining interest in being involved in China ministries among Christians in Hong Kong.3

Surveys on Multiple Identities

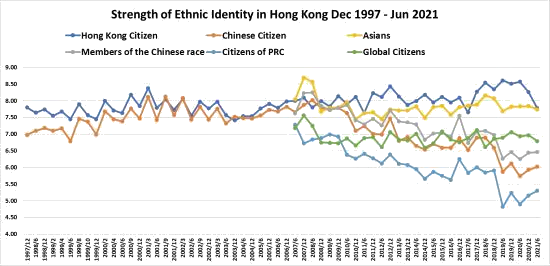

How Hong Kong people identify themselves is a complicated issue. This can be seen in the surveys conducted by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Institute since the Chinese government resumed the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong in 1997. During that time they have periodically surveyed how Hong Kong people perceive their identities. In the first 11 years, the respondents were asked to weigh how strongly they felt they were Hong Kong citizens and China citizens. From 2007 onwards, the respondents were asked to rate how strong he/she identifies with being:

- a Hong Kong citizen,

- a China citizen,

- an Asian,

- a member of the Chinese race,

- a citizen of the Peoples Republic of China,

- a global citizen.

Such highly differentiated categories cause people to consider the various identities that can be distinguished within “one country two systems.” The following diagram shows the historical trends.

Source of Data: Strength of Identity – Combined Charts

Over the past few years, every time the polling result has been reported, columnists and politicians try to put forward their ideological ideas by relating the figures to certain recent social observations. However, these comments are often disputable and viewpoint-based rather than evidence-based because the polling does not contain explanatory factors from the respondents themselves.

Back to the Basic Identities

I wanted to analyze the data further so that something more solid could be deduced.

First, to make the analysis more manageable, I focused on just two basic identities, namely, citizenship of (1) Hong Kong and (2) China instead of considering all six differentiated categories. Part of my reason for this was that I have found no other ethnic identity surveys attempting such a complicated differentiation as in Hong Kong. For example, in Britain, when there was a heated debate over Scottish secession and independence, their ethnic identity survey in 2013 among the white Scottish boiled down to simply three categories:

- Scottish identity (73%),

- Scottish and British identities (21%),

- British identity (5%).

That provided a clear picture of how their national identity and Scottish identity divided and mixed among most of the population.4

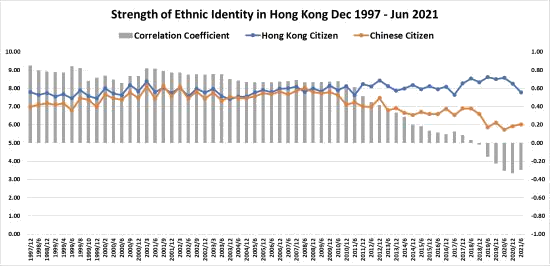

Based on the polling results data provided by the HK Opinion Research Institute, I have plotted the correlation coefficient between the two categories of Hong Kong citizenship and China citizenship as shown in the histogram below. Obviously, over a long period, no matter how the trends fluctuate, the correlation coefficients remained positive from the beginning until mid-2019 when the social unrest broke out. Since then, the correlation coefficient has turned negative.

From a statistics perspective, a positive correlation coefficient implies that when the Hong Kong identity weighs more, the China identity tends to weigh more. By the same token, the rating of the Hong Kong identity tends to drop with the China identity. This was the phenomenon before society burst into social turmoil. On the contrary, a negative number shows that the two feelings oppose each other, and the Hong Kong identity is not compatible with China identity.5

The histogram shows that when society embraced diversity and social inclusion, citizens in Hong Kong would allow both identities to grow or decline together. In a healthy state, the two identities did not implacably oppose each other. Clashes in society broke out when the correlation turned negative. Therefore, it seems that public measures should not aim at suppressing the Hong Kong identity while boosting the China identity. Neither should the Hong Kong identity be promoted to an extent that China identity is overshadowed. We should have a more inclusive attitude towards the growth of both identities to keep “one country two systems” in good shape.

Multiple Identities for Jewish Community in Jesus’ Time

Coincidentally, multiple social ethnic identities can be found in the Jewish community in Palestine in the time of Jesus. The emperor, Augustus appointed Pontius Pilate to take charge of the province. He relied on local leaders to govern the territory. The high priests were the actual administrators in Jerusalem.6 To a certain extent, the administration was like our “one country two systems”. We have our law system different from the mainland in Hong Kong. The high priests in the first century kept the Jewish communities in order by employing Mosaic Law which was different from the Roman law codes. The courts of justice in the Judean province turned to the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem for final decision when they came across difficult cases.7 In a sense, they displayed the key features of the highly autonomous administration in Hong Kong by having independent executive, legislative, and judicial systems.

As such, the Jews also carried multiple social identities in the time of Jesus. They were subjects of the Roman Empire. At the same time, they held on to their Jewish ethnicity within the Greco-Roman culture. Under the inclusive policies of the government, they were granted special rights in the Palestine territory. They were exempted from conscription. They had the religious freedom to worship their God. Respecting their religious law, it was forbidden to summon a Jew to court on the Sabbath, to exact labor from him, or even to compel him to free amusements. They were allowed to tax their members and inflict fines upon them for collecting common funds for their local benefits.8

Despite the inclusive policy, contradiction engendered from the multiple identities was unavoidable. For instance, the Empire actively used the official coins with Caesar’s image to promote the worship of the emperor. This practice conflicted with the Jewish belief. To counteract, the Jewish community in Palestine developed their coinage which was minted locally without bearing the emperor’s image. Although Jews were allowed to use such coins with smaller face value for daily common transactions within their territory, they had to use official coins for paying tax to the government.9

This contradiction formed a scenario for the Pharisees to trap Jesus by asking him whether it was permissible to pay tax to Caesar. But Jesus answered in his wisdom that they should pay to Caesar the things that were Caesar’s; and to God the things that are God’s (Matthew 22:15-17). Jesus did not neglect the earthly national identity. But he reminded them of their prestigious identity as God’s people on top of it. By the same token, as Christians, our ultimate loyalty lies in God. Citizenship in God’s kingdom is our ultimate identity.10 It is worth examining how recognizing our kingdom identity can help us hold on to our faith despite the social changes. The exploration will be presented in the next article.

Endnotes

- 黃焯謙, “公民科開課無書”, 明報新聞網, 2021年9月4日,港聞版, https://news.mingpao.com/pns/港聞/article/20210904/s00002/1630693109034/公民科開課無書-教師嘆不懂考評-新科多法律條文-學生稱缺學習興趣 (accessed September 29, 2021).

- Jason Hung, “Issues & Insights Vol. 20, WP 1 – The Climate of Civil Disobedience: Liberal Studies as a Political Instrument under Hong Kong’s Secondary Education Curriculum”, Pacific Forum, Feb, 2021 on website: https://pacforum.org/publication/issues-insights-vol-20-wp-1-the-climate-of-civil-disobedience-liberal-studies-as-a-political-instrument-under-hong-kongs-secondary-education-curriculum (accessed September 23, 2021).

- 陳智衡, “本土意識對香港教會的影響與挑戰”, 基督教與中國文化研究中心通訊62期,2014年11月,https://resources.abs.edu/本土意識對香港教會的影響與挑戰 (accessed September 23, 2021).

- Ludi Simpson & Andrew Smith, “Who Feels Scottish?”, Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity, The University of Manchester, UK, Aug. 2014 on website: https://policyscotland.gla.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/CoDE-briefing-Who-Feels-Scottish.pdf (accessed September 23, 2021).

- H. Christoph Steinhardt, Linda Chelan Li & Yihong Jiang (2017), ‘The Identity Shift in Hong Kong since 1997: Measurement and Explanation’, Journal of Contemporary China https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1389030 (accessed September 23, 2021).

- Warren Carter, Pontius Pilate: Portraits of a Roman Governor, (Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 2003), p. 47–49.

- Joachim Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus, translated by F. H. and C. H. Cave, (Germany: Library of Congress Catalog, 1969), p. 79.

- Charles Guignebert, The Jewish World in the Time of Jesus, (Oxon: Routledge, 1996), p. 219.

- Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary, (Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2009), p. 524-526.

- 辛惠蘭, “從命?抗命?從新約聖經看順服掌權這”,迎向政治的呼召,雷競業、辛惠蘭編,(香港:中國神學研究院,2017)p.133.

JI Yajie

JI Yajie (pseudonym) has worked with an NGO in China for more than a decade and has the desire to bring the gospel holistically to unreached people in creative access countries.View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.