In this second of a series of posts exploring my understanding of modern Chinese Christianity, I delve into some historical patterns in Chinese religiosity that play important roles in shaping the many ways Chinese Christians have negotiated and lived out their faith amidst the ups and downs of the modern era.

To do so, I utilize three lenses: intercultural relations, ethical action, and church life (more formally articulated as ecclesial and missional living). While the 10-minute segment of my video lecture shared here summarizes all three of these elements, this post will focus on the first of these three lenses: the role of intercultural learning in Chinese religiosity.

From the very outset, you will notice that I prefer the word “religiosity” to “religion.” This is a very intentional choice connected to my interests in lived theology.

Whereas the word “religion” can conjure up conceptions of doctrines, beliefs, rituals, and other formal characteristics associated with institutionalized faith, “religiosity” is more dynamic, diffuse, and fluid. Religiosity has more to do with how a person feels and behaves than what they think or say they believe.

Moreover, expressions of religiosity are not exclusive to one set of beliefs or any single religious tradition or institution. Rather, religiosity is a product of intercultural relations and learning over time across many different contexts. While staying true to some basic assumptions and values, expressions of religiosity are often made up of complex negotiations that integrate different beliefs and behaviors from a variety of sources to foster and maintain a consistent worldview and way of life.

In the case of modern China, historical threads of Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism, and other folk religions are fused with Christianity, Marxism, capitalism, nationalism, and more in the melting pot of modernity that has reordered many spheres of life. Each tradition or culture plays a different role in Chinese religiosity to guide lifestyle. Modern Chinese Christian religiosity is, therefore, contextually tethered to many overlapping commitments.

When reviewing the long arc of Chinese cultural history, I discern two foundational patterns in Chinese religiosity that I argue also influence Chinese Christian religiosity. These are 1) a positive view of human nature and 2) a this-worldly emphasis on pragmatic coherence.

The first rests on a sense that, at its root, human nature leans toward the good. Following this positive view of human nature is an impulse that seeks to cultivate that good in a way that renders positive change. While the source of this positivity differs and the means of unleashing it vary, there is a common commitment to spiritual and ethical self-cultivation.

Second, this cultivation for change is focused on practical rather than systematic or logical coherence. This means that Chinese religiosity is oriented toward adopting practices that produce meaningful results without initial concern for logical or systematic clarity. A this-worldly practical coherence means that contradictions are tolerable so long as the desired ends remain realized.

The reason I believe these assumptions are strongly rooted in Chinese religiosity is because they find expression across multiple forms of religion, philosophy, and culture throughout Chinese history. Whether the vehicle of thought is Confucian, Buddhist, or Marxist—the patterns of behavior employed to realize their faith convictions share common traits (for example, see my post on how Buddhism was re-shaped into a Chinese religion via the philosophical work of Zhuangzi.) I think these patterns are also evident in Chinese Christianity’s modern development.

It is also important to recognize that religiosity takes on different forms in different contexts. When we think of religiosity in the context of a church worship service or prayer meeting, we may imagine practices closely associated with formal religion. But when we consider religiosity in the context of family, workplace, or government, these expressions may appear very different.

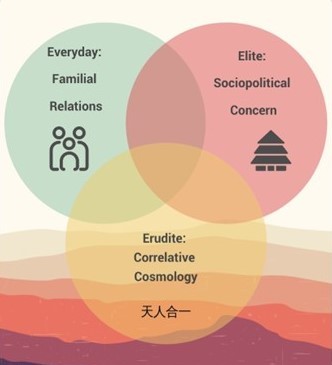

The two orientations in Chinese religiosity I share above, therefore, find their ways to different expressions depending on context. Using a very simplified framework, I see three general spheres of religiosity in Chinese cultural history: the everyday, the elite, and the erudite. In each sphere, the assumptions of human nature and self-cultivation are directed toward ends that are contextually appropriate to their concerns.

In the context of everyday life, the emphasis on cultivating the good toward positive change is centered on the life of the family. Chinese religiosity centered on family life can be seen in ancestor veneration, propriety in familial roles and relations, and filial piety.

In the context of social elites, however, self-cultivation is directed toward the ordering of society most often expressed in social and political philosophies. The well-known Chinese religio-cultural traditions of Confucianism, Daoism, legalism, and others all have explicit teachings on what constitutes good governance and the rulers’ responsibility to cultivate themselves and social harmony.

For the true scholars and philosophers, whom I call the erudite, the desire for cultivation of the good extends to grand proportions that can be understood as a form of correlative cosmology. Correlative cosmology is a fancy way of saying that what takes place amongst the heavens ought to be equally reflected in human life. This orientation is summed up nicely in the Chinese saying tian ren heyi (天人合一), which means to bring heaven and humanity together as one. Christians may recognize a similar sentiment in the phrase, “Thy Kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” It is at this scale we see the marks of what many recognize as “religion,” because it deals with ultimate questions.

What do these patterns in Chinese religiosity have to do with Chinese Christianity, particularly in the past 200 years?

Based on my studies, I believe Chinese religiosity’s orientation toward cultivating the goodness of human nature in the everyday, societal, and cosmic spheres of life can be found in the diverse threads that make up modern Chinese Christian movements. Regardless of whether the movement’s theological beliefs can be considered “liberal” or “conservative,” the ways in which their faith is lived share striking commonalities with historical patterns of Chinese religiosity.

In my next post, I will turn my attention to how the Chinese religiosity articulated in this post plays out in Chinese Christianity’s concerns for ethical action and the life of the church across the twentieth century and summarize the different ways Chinese Christians embody this basic religiosity.

Easten Law

Easten Law is the Assistant Director for Academic Programs at the Overseas Ministries Study Center at Princeton Theological Seminary (OMSC@PTS). His research focuses on lived theology, public life, and religious pluralism in contemporary China. He completed his PhD at Georgetown University, an MDiv at Wesley Theological Seminary, and an MA …View Full Bio

Are you enjoying a cup of good coffee or fragrant tea while reading the latest ChinaSource post? Consider donating the cost of that “cuppa” to support our content so we can continue to serve you with the latest on Christianity in China.