What does it look like to reach second-generation Chinese immigrants for Christ? As pastors serving in English-speaking ministries of Chinese heritage churches, we have been asked to briefly outline the characteristics and needs of reaching the “second generation”1 in Aotearoa New Zealand and offer our insights. Our experiences draw from the specific churches we are privileged to pastor (both English-speaking congregations within a “Triplex” model of church)2 and our upbringing in families that immigrated to New Zealand in the 1990s.3

The Challenges of Second-Generation Life in New Zealand

Children of Chinese immigrants face a range of unique challenges growing up in New Zealand. Experiences of casual racism, pressure to conform to the dominant culture, and an ongoing sense of not belonging is typical among Chinese Kiwis.4 Depending on their age, upbringing, and language ability, the Chinese church becomes both a place of solace (with its familial culture) and sorrow (over how different it is to the rest of their life).

In response, first-generation pastors and Sunday school teachers offer well-meaning sermons on the importance of honoring one’s parents, working hard, and avoiding morally illicit behaviors that bring shame upon the community. Yet rarely does the next generation hear how the Christian faith relates to their own questions around fairness, belonging, gender, and identity.5 While first-generation immigrants typically ask: “How can I belong here?” the next generation usually ask: “Who am I?”6 The gospel message—enculturated through Chinese values and beliefs shaped by Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist thinking—gradually becomes impossible for second-generation Chinese New Zealanders to reconcile with the progressive and post-Christian values in wider society.

Sadly, the result is a silent exodus of the second generation from the Chinese church. Some walk away from Christianity altogether, unable to see God as anything other than an impossible-to-please father. Some fall into cults—former Shincheonji members report a high proportion of second-generation Chinese who are drawn in.7 Others find belonging and acceptance in Kiwi churches with bespoke youth ministries and preaching and worship in English, or in parachurch ministries that emphasize teaching and practices that were avoided by the church they grew up in. One sister shared how it was after joining a campus ministry group that she truly grasped God’s grace and love for her and his heart for the nations.

Reaching the Second Generation in Chinese Churches

Unlike larger diaspora countries, most Chinese churches in New Zealand have fewer than 100 members with an even smaller number in churches outside the main cities. Accordingly, most struggle to start, let alone maintain, a dedicated English ministry. If one exists, it is typically led by the oldest youth or adults with English fluency. In rare cases, a youth or English pastor shoulders the responsibility. The second generation they serve are usually a smaller group within the church. Some choose to stay, hoping to influence and shape their church beyond its immigrant-focused culture. What are some ways we can better serve them?

A need to contextualize the gospel for second-generation Chinese.

A leader in a Kiwi evangelical church once shared, “We keep picking up young adults who grew up in Chinese and Asian churches who don’t seem to have heard the gospel before.” While this may be true for many, what we have observed is not a failure to proclaim the gospel, but one that is poorly contextualized to the second generation.8 Often, the first generation conflates “good news” with cultural expectations like finding a well-paid job, getting married, and providing grandchildren. Language remains a key barrier for the second generation who rarely have an adequate grasp of Chinese church vocabulary, let alone the archaisms of the Chinese Union Version translation of the Bible. An emphasis on moral obedience without demonstrating how it is empowered by the gospel results in a generation who do not experience God’s grace. Once, after hearing how sin is not just a behavior issue but a heart issue, a brother remarked that it was the first time he had heard this in his Chinese church. If the existential cry of the second generation is “Who am I?” then we do well to preach that only by being united in Christ—through repentance and faith in his finished work on the cross—will we find an identity that never changes or loses its worth and motivates us for the good works God has prepared for us (Ephesians 2:8–10).

A need to equip the saints for the work of second-generation ministry.

Ephesians 4:12 reminds us that the role of pastors and teachers is “to equip the saints for the work of ministry.” Chinese churches in New Zealand must find ways to train and equip the second generation for gospel ministry that the first generation cannot accomplish on their own. This may require a willingness to step beyond a hierarchical structure and share meaningful responsibility with the next generation. Training and leadership opportunities should be offered based on character and competence, not just seniority or a connection to important family members. We have also encouraged second-generation members to pursue theological studies, trained them to serve as lay preachers at each other’s churches, and connected them with the wealth of training materials and resources offered in English.

Yet, if the harvest is plentiful among the second generation, the laborers are certainly few. More than likely, there is already an immigrant church near you with a younger generation hungry to hear the good news about Jesus in their heart language of English. They need someone willing to cross cultures, enter their world, listen to their unique challenges, and help them anchor their identity in Christ; in other words, someone with a missionary heart. For those unable to serve in China at present, would you consider laboring among the unreached second-generation Chinese among us?

A need for unity (not uniformity) between first- and second-generation believers.

“We are separated quite independently, and it feels like we don’t have any business with one another.”

“We know each other but we don’t really have any personal relationship.”

When researching my [Ting’s] master’s thesis,9 I would hear comments like these from church leaders and witness the stark differences between Chinese- and English-speaking congregations. The change from a mono-ethnic to multi-lingual ministry poses a challenge to the unity of the church. While there are numerous biblical principles to help us counter the division and conflict within a multi-lingual church, the Apostle Paul’s metaphor of the body of Christ in 1 Corinthians 12:27 is a highly significant one: “Now you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it.” We have Christ, the risen one, the perfect deity and perfect human, who heads the church that the Lord created and the Spirit maintains.

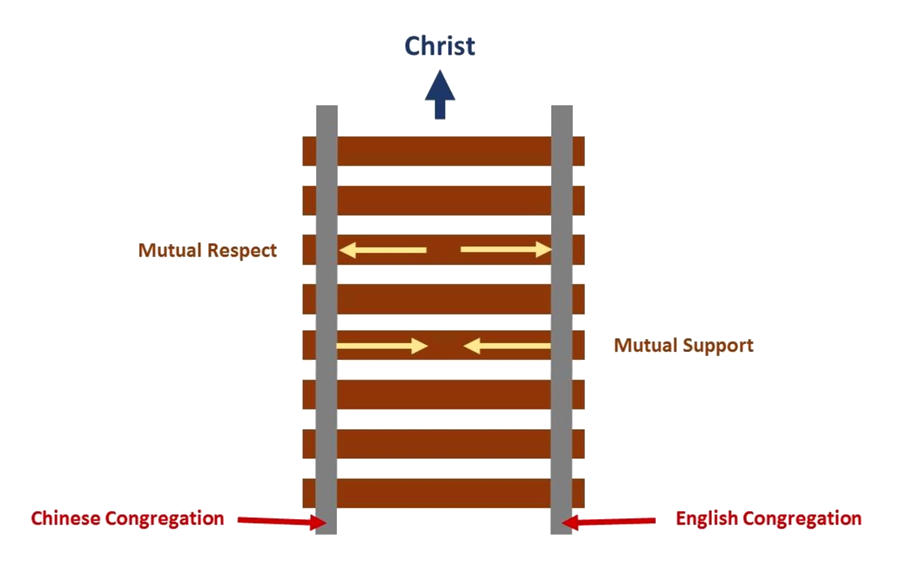

Yet, given the different needs of first- and second-generation believers, unity involves both maintaining the oneness of each Chinese church while also embracing the diversity of each congregation. Consider how a railroad track can only carry a train forward when its two rails are set a fixed distance apart by sleepers (or “ties”). In the same way, Chinese and English congregations are like two parallel rails to carry the train—the mission of the church.

We should take care that unity does not become uniformity. For example, driven by the fear of potential division, Chinese churches often attempt to pull the first- and second-generation congregations together through running combined events like prayer meetings, worship, and outreach activities. While these no doubt promote mutual support between the two, churches should also promote mutual respect by accepting and appreciating the differences in language, culture, and worldviews of each group. With this kind of unity, the mission of Christ can progress “full steam ahead” among the Chinese diaspora into future generations.

A need for thankfulness for second-generation Chinese ministry.

Whenever I (William) am asked what our church is like, my answer often needs clarification. “Yes, the English congregation of the Chinese church. No, not the English-speaking church right next door.” After struggling through yet another bilingual meeting, or making yet another cultural mistake, it can be tempting to wonder whether the needs of the second generation are better met elsewhere. Might a parachurch group that champions the Asian voice solve their needs? Could the English church next door do a better job? However helpful they may be, I believe God’s manifold wisdom (Ephesians 3:10) is still being shown through the Chinese church. As long as New Zealand continues to attract immigrants, there is a place for the great commission to be fulfilled among the second generation.

The stories of other leaders in New Zealand and overseas have encouraged me that a ministry focused on the second generation can be biblically faithful and can bear gospel fruit over time.10 A missions colleague shared that second-generation Chinese who learn to find their identity in Christ become some of their most effective missionaries and global-minded supporters. For those who choose to teach and pray, love, and stay with the second generation, may God give you eyes to see the kingdom potential in the brothers and sisters you serve. There is, and will be, much to be thankful for.

Endnotes

- While acknowledging a range of overlapping but distinct upbringings (that is, 1.5 generation, returnees), we have adopted the definition of the second generation as, “people who were born in New Zealand with parents who immigrated from East Asian countries such as mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau [including] people of Chinese descent who live outside of China, such as Malaysian Chinese, and Singaporean Chinese.” Melissa Cheung, “Second-generation Chinese New Zealanders’ Experience of Negotiating between Two Cultures: A Qualitative Study” (master’s thesis, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand, 2019), 3.

- That is, three different congregations functioning under one leadership. For an overview of different types of multi-generational Chinese church structures, see chapter 1 of Benjamin C. Shin and Sheryl Takagi Silzer, Tapestry of Grace: Untangling the Cultural Complexities in Asian American Life and Ministry (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2016), 7–30.

- It is predicted that by 2043, one in four of New Zealand’s total population will be Asian, including nearly 500,000 of Chinese ethnicity. See “Population projected to become more ethnically diverse.” Statistics New Zealand, Media release May 27, 2021, accessed May 17, 2022, https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/population-projected-to-become-more-ethnically-diverse.

- For example, see Stephanie Chan’s “Reflections from a Recovering Banana.” Metanoia NZ, August 21, 2020, accessed May 24, 2022, https://www.metanoianz.com/blog/reflections-from-a-recovering-banana.

- At the risk of over generalizing, a key difference between New Zealand and American cultures is New Zealand’s stronger emphasis on “fairness” rather than “freedom.” See David Hackett Fisher, Fairness and Freedom: A History of Two Open Societies: New Zealand and the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- See a similar discussion in Daniel L. Wong, “The Asian North American Experience,” in Finding our Voice: A Vision for Asian North American Preaching, ed. Matthew D. Kim and Daniel L. Wong (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2020), 21-48.

- For example, see Vanessa Chan’s testimony of how Shincheonji recruited her in Wellington, New Zealand. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/shincheonjinz/posts/117113944234951 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tKr1FmOyQ0o. Accessed May 17, 2022.

- For a helpful discussion on preaching with high cultural intelligence, see Sam Chan, “How to Address a Topic Culturally,” in Topical Preaching in a Complex World (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2021), 122–148.

- E. Ting Wong, “A Challenge for Unity: Inter-Congregational Relationship in Chinese Immigrant Churches in Auckland”(master’s thesis, Carey Baptist College, Auckland, New Zealand: 2016).

- For example, Daniel Chan, “Helping Second Generation Immigrants Love the Immigrant Church.” 9 Marks, June 22, 2020, accessed May 17, 2022, https://www.9marks.org/article/helping-second-generation-immigrants-love-the-immigrant-church/.

Image credit: courtesy of the authors

William H. C.

William H. C. (張偉亮傳道) is the English Pastor at Pakuranga Chinese Baptist Church (東區華人浸信會) in Auckland, New Zealand. He was first introduced to Jesus as a 16-year-old when someone took the time to sit down with him and explain the good news. In his spare time, he enjoys cycling with …View Full Bio

E. Ting Wong

Rev. E. Ting Wong (黃懿珽牧師) is the English Minister at Evangelize China Fellowship Holy Word Church of Auckland (中國佈道會奧克蘭聖道堂). His Master of Applied Theology thesis explored the inter-congregational relationships between first- and second-generation believers in New Zealand Chinese immigrant churches.View Full Bio