During the last three decades opportunities have greatly increased for cooperation between Christians inside and outside China, both in strengthening the church in China and in advancing the gospel beyond China’s borders. As China and its church have undergone rapid change, varying perceptions have emerged inside and outside China regarding the situation of the Chinese church, its priorities, needs, and expectations for working with the church outside China.

In order to better understand these perceptions and their implications for collaborative ministry, the China Gospel Research Alliance (CGRA)[1] conducted a survey from September 2015 to May 2016 of Christian leaders in China and representatives of churches and organizations outside China that work with these leaders. A total of 1,200 written surveys were completed, and 432 face-to-face interviews were conducted with Chinese Christian leaders from every province in China except Tibet. More than 200 overseas church and organization leaders were polled via an online survey, and forty took part in face-to-face interviews. These included agency leaders, board members, field workers, other agency staff, pastors, and financial supporters or volunteers. Most lived in Asia, with 37 percent being in mainland China and 16 percent in Hong Kong or Macau. Of the overseas respondents, 32 percent identified themselves as Chinese.

Discussion of respondents’ expectations for working together, along with their perceived difficulties in cross-cultural partnerships, is provided elsewhere in this issue. Here we will examine the characteristics of the respondents, both Chinese and overseas, in an effort to learn more about the current state of the church in China.

Characteristics of Respondents

The Christian leaders surveyed admittedly represent a “convenience sample,” as these leaders were primarily accessed via conferences being held specifically for believers from China. Three of the conferences had cross-cultural missions as their theme; thus, it may be surmised that these participants came with bias toward, and likely some prior involvement in, mission activity. In this sense the sample cannot be viewed as representative of the entire church in China. Nevertheless, as the church in China prepares to engage in cross-cultural ministry, and as more overseas churches and organizations prepare to help them in this endeavor, our sample represents a significant group of leaders who will likely be the ones to engage with overseas entities in the decades to come.

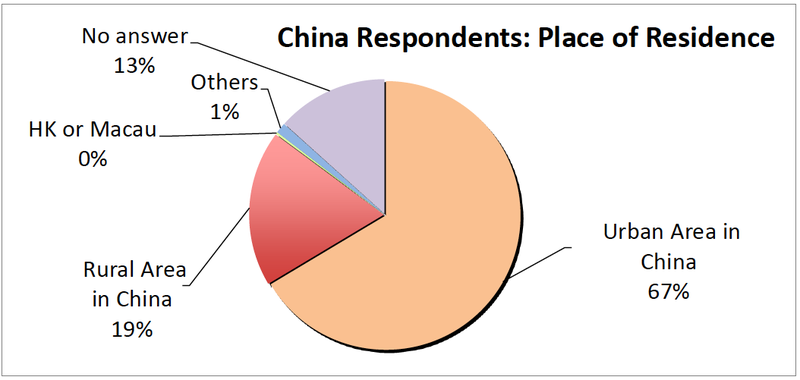

As the China sample is mainly composed of Christians in China’s unregistered church, which makes up the largest segment of Christians in China, the data speak mainly to the dynamics of the unregistered church as it makes its transition from a primarily rural to an urban phenomenon.

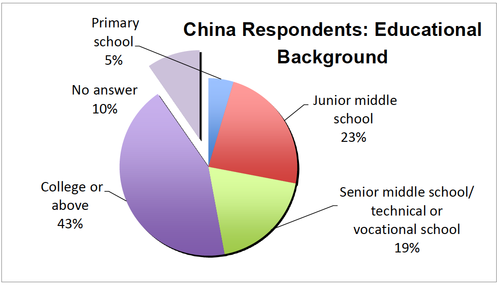

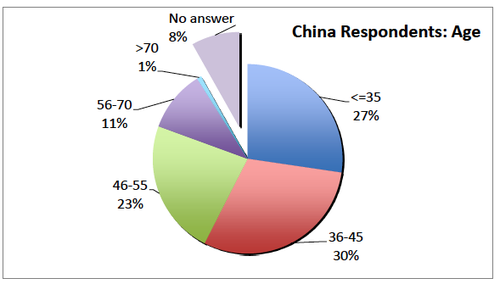

Although the majority of the China respondents were of urban background, a significant segment representing the rural church was included as well. Two-thirds of urban respondents were under the age of 45, while two-thirds of rural respondents were between the ages of 36 and 55. Just over half of respondents were male and 39 percent female (ten percent no response). Most respondents were married. Forty-three percent of all respondents had a college education or above, and more than 60 percent had received some theological training.

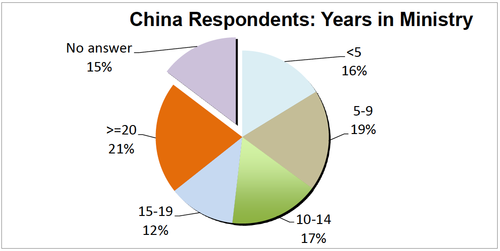

There were roughly an equal number of full- and part-time workers. Most had been involved in ministry for less than 15 years, but roughly one-fifth had 20 or more years’ experience.

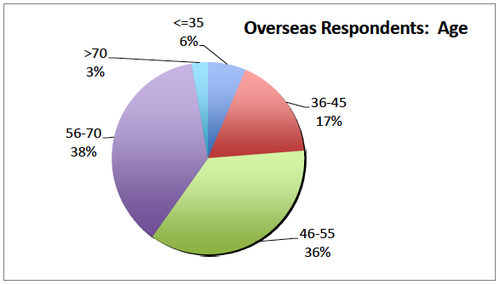

Comparing the demographics of the China respondents and those from outside China who serve with them suggests a significant generational difference. Overseas respondents were predominately male and tended to be older than the Chinese respondents, with more than two-thirds being over age 45. In contrast, 57% of the China respondents were aged 45 or under.

Health of the Church

Participants were given a list of ministry types and asked to indicate how well they felt their churches were doing in each area as well as which ones they felt were priorities. Urban respondents gave the church higher marks than rural respondents in all ministry areas except for training coworkers and pastoring the next generation, where the respondents were roughly similar. Female China respondents felt the church was doing better than male respondents in the area of encouraging financial giving.

|

Assessment of Ministry Areas by China Respondents |

|||||||

| Ministry Areas | Not at all ideal | Not ideal | Acceptable | Fairly ideal | Very much ideal | No answer | Total |

| Discipleship | 8.0% | 30.3% | 34.0% | 15.9% | 3.7% | 8.1% | 100.0% |

| Training for co-workers | 4.4% | 30.4% | 36.4% | 16.1% | 3.3% | 9.4% | 100.0% |

| Leadership development | 10.3% | 37.5% | 23.0% | 11.8% | 3.6% | 13.8% | 100.0% |

| Church planting | 9.4% | 28.3% | 30.5% | 13.6% | 3.8% | 14.4% | 100.0% |

| Church admin. | 6.2% | 27.0% | 33.7% | 15.5% | 3.4% | 14.3% | 100.0% |

| Seminary training | 2.3% | 17.0% | 37.6% | 25.0% | 4.8% | 13.3% | 100.0% |

| Guarding against cults | 0.9% | 4.5% | 35.3% | 34.9% | 11.8% | 12.6% | 100.0% |

| Missions | 10.6% | 32.3% | 26.3% | 15.8% | 4.2% | 10.9% | 100.0% |

| Pastoring next generation | 3.8% | 22.3% | 38.3% | 21.7% | 4.8% | 9.3% | 100.0% |

| Encouraging financial giving | 3.2% | 19.8% | 38.3% | 21.1% | 6.1% | 11.6% | 100.0% |

In the areas of seminary training, protecting against cults, pastoring the next generation, and encouraging financial giving, China respondents were more likely than overseas respondents to indicate the church was doing well; overseas respondents saw the church doing better than did China respondents in the areas of discipleship, training for coworkers, and church planting.

Ministry Priorities

The top priorities for Chinese respondents were missions, pastoring the next generation, discipleship, and seminary training. Urban respondents viewed discipleship as a higher priority than rural respondents. Full-time workers ranked leadership development higher than did part-time respondents. More female than male respondents included pastoring the next generation among the church’s top three priorities.

| China Respondents: Priority Ministry Areas by Location of Residence (Top Three Areas Selected by Each Respondent) |

||

| Ministry Area | Location of Residence | |

| Urban Area in China | Rural Area in China | |

| Discipleship | 55.5% | 38.8% |

| Training for coworkers | 24.7% | 22.3% |

| Leadership development | 35.7% | 43.7% |

| Church planting | 12.7% | 7.8% |

| Church administration | 19.3% | 13.6% |

| Seminary training | 41.3% | 40.8% |

| Guarding against cults | 3.2% | 3.9% |

| Missions | 49.9% | 59.2% |

| Pastoring the next generation | 49.9% | 59.2% |

| Encouraging financial giving | 5.4% | 4.9% |

For overseas respondents the top three priorities were discipleship, leadership development, and missions, while seminary training and pastoring the next generation were ranked considerably lower in comparison to the China responses. Overseas respondents also ranked financial giving as a higher priority than did China respondents.

| Priority Ministry Areas by China and Overseas Respondents (Top Three Areas Selected by Each Respondent) |

||

| Ministry Area | China Respondents (1) | Overseas Respondents (2) |

| Discipleship | 50.9% | 62.0% |

| Training for co-workers | 25.0% | 22.8% |

| Leadership development | 38.0% | 62.0% |

| Church planting | 11.5% | 14.1% |

| Church administration | 17.5% | 15.2% |

| Seminary training | 39.8% | 17.4% |

| Guarding against cults | 3.5% | 8.2% |

| Missions | 53.5% | 55.4% |

| Pastoring the next generation | 51.9% | 35.9% |

| Encouraging financial giving | 5.2% | 15.2% |

Note: (1) Response rate of about 50% (2) Response rate of about 85%

Discipleship is recognized across the church and among those overseas who serve the church in China as a critical need. The fact that urban Christian leaders identify discipleship as more of a priority perhaps suggests that they are more aware of areas where the church has fallen short in developing believers, for example, in character or in their ability to work with one another. On the other hand, lacking strong Christian traditions in their background, urban leaders, many of whom are first generation believers, may be responding to their own felt need to build a foundation for spiritual formation that has hitherto been lacking. Seeing how the rampant secularism and material temptations of urban life affect the quality of believers’ lives, these urban leaders may also have a greater awareness of the need for personal spiritual development in order to counter these prevailing cultural trends.

China respondents’ identification of pastoring the next generation as a priority speaks to both the growing phenomenon of Christian education in China as well as concern about the church’s future. Young urban Christian families are increasingly looking for alternatives to the state-run education system which is largely built around preparation for test taking, culminating in the nationwide university entrance exam, and which is overtly atheistic. The fact that providing educational services was listed as one of the top three ways in which the church is engaging with society also suggests the importance of this area.

Looking at the larger issue of leadership succession within the church, there is a sense among some traditional rural networks that they may have lost much of the next generation due to urbanization and to the fact that many within that generation have not shared their parents’ Christian commitment and zeal for gospel ministry. Many of the independent urban churches are led by first-generation Christians who have not experienced intergenerational ministry. Hence the popular saying, “The rural church has no children; the urban church, no fathers.”

Leadership development appears to be a higher priority for overseas respondents (62 percent) than for China respondents (38 percent). Yet nearly 40 percent of China respondents saw seminary training as a priority, compared with only 17.4 percent of overseas respondents. As the term “leader development“ has been used loosely in China ministry circles to refer to everything from formal theological training to peer mentoring and coaching, perhaps some of the apparent discrepancy here is simply a matter of terminology; some activities identified by overseas respondents as leadership development may not be recognized as such by Christians in China.

Social Engagement

Participants were asked to indicate the motivation for the church to engage with society and to list the particular areas of engagement. Approximately 62 percent of China respondents indicated their churches are engaging with society, but only 28 percent mentioned the specific ways in which they are doing so. Of the overseas respondents, about 60 percent indicated that churches they work with in China are engaging with society. Urban churches were most likely to be involved in various types of social engagement with the most common areas being: providing family services, caring for those on the margins of society, or providing educational services. Urban respondents’ churches were more likely to provide medical services, conduct cultural activities in the community, and use media to promote the gospel.

Mission Involvement

Given that the majority of China respondents in this study were surveyed while attending mission-related gatherings outside China, it does not come as a surprise that they demonstrated a relatively high degree of involvement in missions-related activity. The most common involvement was mobilizing their congregations to support missionaries through financially giving and prayer (46 percent of China respondents), followed by providing hospitality for missionaries (34 percent), inviting missionaries to the church (33 percent), setting up a mission department in the church (28 percent), sending short-term teams to ethnic minority areas, (28 percent), and sending their own missionaries from the church (28 percent).

Both urban and rural churches are involved in cross-cultural mission, albeit in some different ways. While both are building mission sending structures, urban churches are more likely to have regular mission Sundays, to invite missionaries to share in their churches, to set up mission departments within the church, and to mobilize the congregation to support missionaries. Rural networks may have set up sending structures within their networks, but this activity may not be “owned” by the local churches. Stand-alone urban churches, on the other hand, are more likely to have church-based mission programs.

Religious Policy and Restrictions on the Church

China participants were asked whether they had experienced certain types of restrictions and, if so, when they had experienced these.

Educational background was a factor in how China respondents perceived restrictions on religious activity. Well-educated Chinese Christians perceived more severe religious restriction than others. Christians at middle age tended to perceive less restriction than the younger ones. Those who were over 55 have memories of the Cultural Revolution, when families were broken apart, teachers and officials publicly shamed, schools closed, and the Red Guard allowed to inflict terror across China. As religion was completely banned during that time, for this age group the current religious policy situation in China looks quite positive.

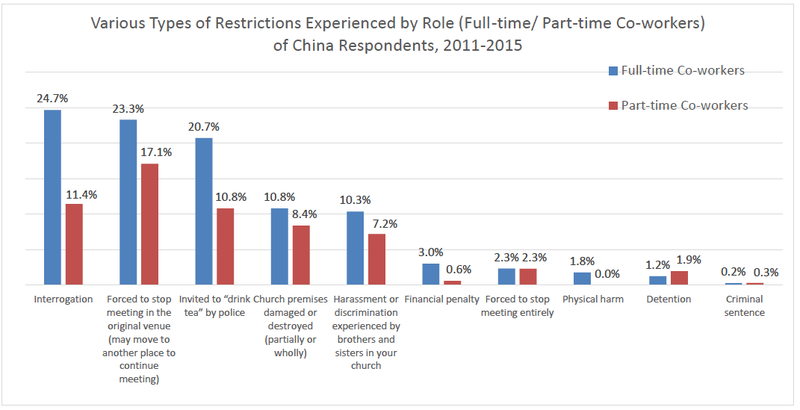

Of the specific kinds of restrictions, being forced to stop meeting in a particular location (with the option of moving to another location), interrogation, and being invited to “drink tea” (being asked to report on the activities of one’s church) by police were the most common types of restriction reported in the last five years, with more restrictive measures such as fines, detention, or criminal sentences becoming more rare. Full-time workers were more likely than part-time workers or others to have experienced any kind of restrictions. To put these figures into perspective, it is important to note that, except for having to move the church location and, in the case of full-time workers, of being interrogated, the majority of China respondents indicated that they had not directly experienced any of the specific restrictions mentioned in the survey.

As China’s church makes its transition from a primarily rural, peasant movement on the edges of society to having a dynamic and increasingly influential urban presence, its needs and its role within the society are in flux. While it is impossible to gain a complete picture of the church’s current situation, increased opportunities to engage with China’s church have allowed a new degree of visibility into the life and ministry of Chinese Christians, enabling those who serve to better understand their own role in this rapidly changing environment.

Brent Fulton

Brent Fulton is the founder of ChinaSource. Dr. Fulton served as the first president of ChinaSource until 2019. Prior to his service with ChinaSource, he served from 1995 to 2000 as the managing director of the Institute for Chinese Studies at Wheaton College. From 1987 to 1995 he served as founding …View Full Bio