Introduction

China has launched a major geopolitical/economic initiative at the same time that mission outreach awareness has been growing among the house churches of China. The confluence of these two developments in the last five years has created new opportunities and challenges for Chinese churches and Christians in reaching out globally in missions. This article provides a general background and overview of these developments.

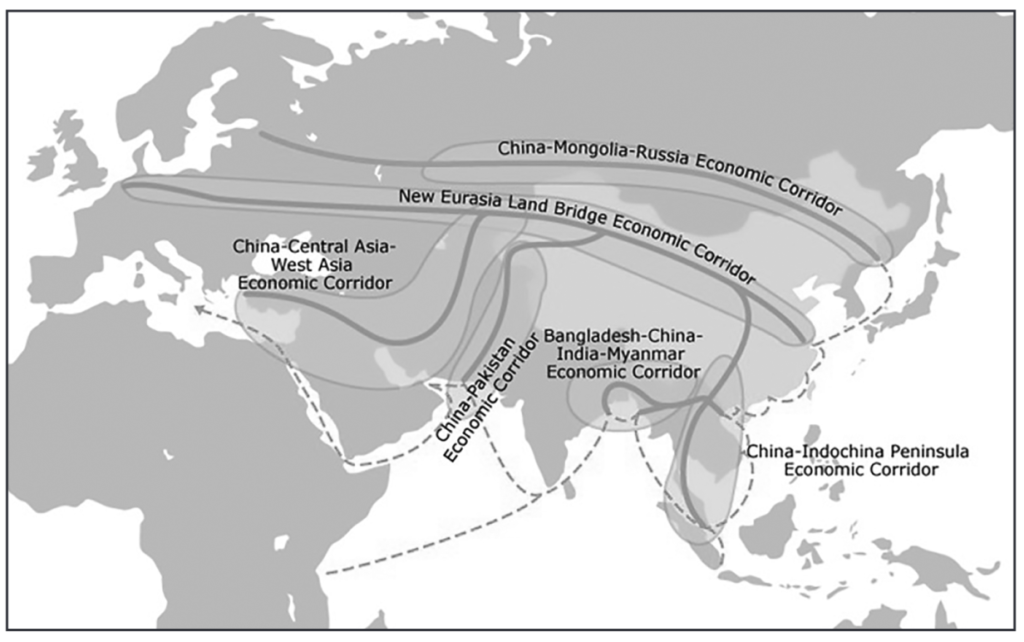

The Belt and Road Initiative

In 2013 Chinese president Xi Jinping, in state visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia, first started talking about the New Silk Road and the maritime Silk Road which quickly became One Belt and One Road (OBOR) and later the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Since that time the BRI has become a major part of China’s external relations. It was written into the Chinese Communist Party constitution in 2017 and government work plans afterwards. BRI has become a major part of China’s foreign relations, international development, as well as domestic economic programs.

From the perspective of outside countries, China’s BRI program has been characterized as a geo-strategic plan for building a new type of international order with China at the center. BRI has been characterized as debt diplomacy with some Western countries blaming China for creating “debt traps” for other developing countries. Others have referred to BRI as a form of neocolonialism.

What cannot be disputed is that BRI covers a significant part of the world:

Statistics provided1early in its development indicate that BRI encompasses:

- more than 60 countries,

- one third of global economic activity (GDP),

- 65% of global population.

At the 2019 Belt and Road Forum, China stated that 125 countries and 29 international organizations have signed BRI cooperation documents with China.2

Within China, BRI is discussed in terms of achieving shared growth and win-win outcomes through dialogue and collaboration, building a new platform for international trade and investment, raising up new practices in global economic governance, and contributing China’s wisdom for building a global community with a shared future for humanity.

These two perspectives and ways of describing BRI are far apart. However, for anyone interested in the unreached and unengaged areas and peoples of the world, the overlap with BRI countries is unmistakable and intriguing.

Chinese Christians and BRI

Regardless of how you see BRI and which voices you choose to listen to, it is also important to hear what Chinese Christians say about BRI. As early as 2015, I have heard Chinese Christians refer to BRI as God’s plan for the Chinese church. Just as the Roman Empire provided and enforced a peaceful and secure environment for commerce and travel, and the Roman roads and ports were used by the early church and the Apostle Paul in the spread of the gospel, Chinese believers see the Chinese government’s BRI plan as part of God’s plan to use the Chinese church in mission. Many see and talk about BRI as God’s road and opportunity for them to move out in mission.

The timing of BRI is also significant for mission from China.

During the past 40 years of China’s development there has been a consistent external focus on countries outside of China. If you read a Chinese newspaper and compare it to any North American newspaper for the same time period, you will find the Chinese newspaper has a much higher percentage of articles, news, and information about foreign countries. Learning foreign languages has been part of school curriculum from elementary school onwards for the past four decades. As the standard of living has risen in China, Chinese have begun to move out as students, business people, and tourists. In 2019, China had over 160 million outbound tourists.3 No matter where you go in the world today as a tourist, student, or business person, you are highly likely to run into Chinese citizens. Mainland Chinese churches that can afford to arrange tours to the Holy Land for its members also have the financial capability to join the global mission movement in sending out their own cross-cultural workers.

During this same four-decade time period, the church in China has also begun to look more globally. About 10-20 years ago the Back to Jerusalem (BTJ) movement4 was popular among the rural house church networks. This movement has historical links to mission movements to China’s western provinces that started before 1949. While exact numbers are hard to confirm, thousands of workers were sent to western China and beyond. In more recent years, the Mission China 2030 (MC2030) movement5 among the urban churches set a goal of sending 20,000 cross-cultural missionaries from China by 2030. Thousands of churches and individual Christians were exposed to cross-cultural missions for the first time.

Both the BTJ and MC2030 have had their detractors for various reasons. Despite these criticisms both movements have played an important part in raising awareness of cross-cultural mission and helping to mobilize churches and individuals.

Opportunities for Mission along the BRI

With China maintaining a continued long-term focus and engagement with these areas of the world and increasing all forms of trade and interaction, it is only natural that Chinese Christians will have a multiplicity of opportunities to work and serve in cross-cultural settings.

As part of its BRI emphasis, the Chinese government has also increased its support for international students from BRI countries studying in China. China previously announced providing 10,000 government scholarships annually to students from BRI countries.6 China now has the third largest group of international students globally.7 Chinese churches have opportunities in China’s major cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Chengdu, Xian, and others to reach out to a growing number of international students from a variety of countries that are part of the BRI. This new type of international student ministry (ISM) is an important ministry opportunity and training opportunity as churches begin to engage and think about ministry beyond their borders.8 As these BRI international students complete their degrees, graduate, and return to their home countries this also creates new opportunities for outreach and ministry along the BRI roads.

There are also opportunities in education. As China has increased its involvement in countries around the world, the number of people learning Chinese internationally has increased greatly. In early decades of China’s opening to the outside world, those who could teach English as a second language (ESL) were in high demand to teach in Chinese universities. Today, we are seeing a similar need and demand for teaching Chinese as a second language (CSL) in countries around the world. Teaching Chinese is a means for many Chinese to find work in other countries. For Chinese Christians this is an opportunity to have a clear identity, provide a needed service, support themselves and their families, and be engaged with local people in countries across the BRI world. China is also investing in the study, teaching, and research in the languages, cultures, and background of the BRI countries. There are opportunities for those in education in China and beyond.

There are opportunities in traditional church and mission work. Chinese churches and agencies are finding opportunities to do traditional ministry and church planting. Sometimes these are independent efforts done by Chinese churches and agencies alone. In other cases there are partnerships and collaboration with other international mission agencies. Two years ago I was visiting a church in Chicago and heard one of their short-term teams share about their summer mission trip. I understood they were focused on working with refugees in Jordan. As they shared about their experiences, I realized these American church members had been assisting and supporting cross-cultural workers sent from China reaching out to refugees in Jordan.

A large sphere of opportunity is business as mission along the BRI. As part of its economic program, the Chinese government has been encouraging companies at all levels to go out (走出去) and seek new markets and new business opportunities outside of China. This emphasis and effort has been enhanced with the emphasis on BRI. Christian entrepreneurs with a missional purpose will find many opportunities to seek new business opportunities along the BRI that can also serve a missional purpose.

Any vision the size of BRI will bring a wide range of opportunities for individuals and churches that have a missional heart and vision to see the gospel taken to every people and every country. China has reached a stage in its economic development and the church has a growing awareness of its responsibility for following God in mission. This combination will result in multiple new approaches and opportunities among the BRI countries.

Challenges for Mission along the BRI

One of the lessons of church history is that challenges and opposition often go hand-in-hand with outreach and the expansion of the church. We should not be surprised that these new mission movements are also encountering challenges. Some challenges are common to cross-cultural workers from other countries and some are unique to China’s situation.

One of the challenges is finding appropriate ways to partner with international mission agencies, other Chinese agencies, and local churches. For example, there are areas where some of the early BTJ movement workers from China’s rural church networks have continued to work for more than a decade. Now new workers from the urban churches are arriving and could benefit from the lessons, experience, and wisdom of these seasoned Chinese workers. However, because of the differences between the rural and urban churches back in China, these two kinds of workers seem to rarely be working together.

Another challenge would be the lack of mission infrastructure to support Chinese workers. This would include team organization and leadership, opportunities for language and culture learning, appropriate children’s education, member care, and so on. The author is not aware of any Chinese international school across the BRI areas available to Chinese workers that can educate their children to the level that they can return to China to take the university entrance exams (高考) and do their university studies in China. There are examples of small teams who have spent a decade in a foreign country without learning the local language and culture. This greatly impacts their ability to be effective in a new culture and reach local people. A small percentage of workers will be like the Apostle Paul with multiple gifts, great faith, tremendous intellect, and single-minded focus. The majority of workers will find the lack of support in these areas becomes a series of confusing and confounding challenges to their life and ministry.

The history of Western mission outreach to China has long been tainted by missionaries who came to China on the back of their government’s might and economic power. Chinese school children learn about this period as a “century of humiliation” that continues to impact Chinese society. Now that China’s global importance, economic size, and impact has increased, Chinese workers along the Belt and Road countries also face a similar challenge of association with a powerful government and charges of neocolonialism. Fortunately, Chinese mission leaders are more aware of these negative possibilities and are learning from the lessons of the past.

Another area of challenge is the expansive role of the Chinese government along the BRI. From the Chinese government’s point of view, the activities of Chinese missionaries may not be aligned with the goals and objectives of their government. In 2018 two Chinese workers were martyred in Pakistan.9 Every country’s government is shocked and concerned when their citizens are harmed for any reason while visiting or living in a foreign country. As the Chinese government understood what these two workers were doing, they became concerned that cross-cultural workers of this kind would have a negative impact to their BRI hopes and objectives. Following this incident there were investigations both outside and inside China to determine who was related to these workers and what kind of work they were doing.

A final area of challenge is the pressure that sending churches are currently receiving in China. There are Chinese workers, already overseas, who have seen their supporting churches closed, reorganized, or suppressed. Suddenly their source of support has been cut off or greatly diminished as the church has refocused on its own survival.

Looking at the situation with Western eyes, we often focus on what cannot be done. From discussions with Chinese Christians about the same situations, more often there is a focus on what can be done and what should be done somehow. The challenges are not ignored but faced in attitudes of trust and faith that God has appointed them to go and make disciples. The focus is on the open doors and Jesus’ promise to be with them always.

Conclusions

As China and the Chinese church have developed over the past four decades, the opportunities and motivation for mission among Chinese Christians have increased greatly. In the past seven years as China has developed its Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese Christians have gained a vision for the opportunities (and even responsibilities) that God has put before them. We are seeing multiple streams and efforts from the church all across China. Encompassing more than half of the countries and populations of the world, the BRI world is already an important area for mission. The emergence of Chinese missions and Chinese missionaries will add a new facet to the work that the Holy Spirit is doing among Chinese churches and in the BRI countries.

Endnotes

- For more information see, “Full text: Action Plan on the Belt and Road Initiative,” The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, March 30, 2015, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/publications/2015/03/30/content_281475080249035.htm; Andrew Chatzky and James McBride, “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 28, 2020, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative, and “Belt and Road Initiative (BRI),” European Bank, https://www.ebrd.com/what-we-do/belt-and-road/overview.html.

- See Zhou Jin, “China Says Belt, Road Will Not Get Involved in Territorial Disputes,” China Daily, April 16, 2019, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/home/rolling/85859.htm.

- See “2019 China Tourism Facts & Figures,” Travel China Guide, October 9, 2019, https://www.travelchinaguide.com/tourism/2019statistics/.

- For more information about BTJ see “What Is Back to Jerusalem?” Back to Jerusalem, https://backtojerusalem.com/about/ and Wen Mu, “The Present and the Future of the Back to Jerusalem Movement,” ChinaSource, April 25, 2006, https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/articles/the-present-and-future-of-the-btj-movement-a-view-from-the-church-in-china.

- For more information about MC2030 see Karin Butler Primuth, “Launching China’s Biggest Missionary Sending Initiative,” ChinaSource, November 13, 2015, https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/blog-entries/launching-chinas-biggest-missionary-sending-initiative/ and ChinaSource Team, “’Mission China in 2030’ in Korea,” ChinaSource, October 25, 2016, https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/chinese-church-voices/mission-china-2030-in-korea/.

- See “Full text: Action Plan on the Belt and Road Initiative,” The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, March 30, 2015, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/publications/2015/03/30/content_281475080249035.htm.

- For more information see Phil Jones, “International Students in China an Unreached Diaspora,” ChinaSource, October 6, 2017, https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/blog-entries/international-students-in-china-an-unreached-diaspora/.

- For more information see Phil Jones, “The Birth of ISM in China,” ChinaSource, January 25, 2019, https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/chinasource-blog-posts/the-birth-of-ism-in-china and Phil Jones, “International Student Ministry in China,” October 22, 2018, https://www.chinasource.org/resource-library/ebooks/international-student-ministry-in-china.

- See Yang Sheng, “Pakistan Says Chinese Hostages Killed by IS Were Preachers,” Global Times, June 13, 2017, http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1051346.shtml.

Peter Bryant

Over the last 30 years Peter Bryant (pseudonym) has had the chance to visit, to live for extended periods of time, and to travel to almost all of China’s provinces. As a Christian business person he has met Chinese from all walks of life. He has a particular interest in …View Full Bio